|

WRIGHT BROTHERS National Memorial |

|

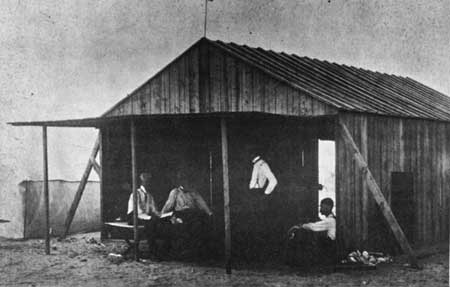

Wright camp at Kitty Hawk, 1900. The campsite of

1901—3 was about 4 miles south of this site.

Glider Experiments, 1900

At Dayton, the Wrights began to assemble parts and materials for a full-size, man-carrying glider to test their method of warping the wings to achieve lateral control, and a forward rudder for fore-and aft balance. In September 1900 Wilbur undertook the journey to Kitty Hawk. Orville followed him later. At the turn of the century such a trip to the isolated village required time and patience. It lies on the Outer Banks of North Carolina between broad Albemarle Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. Then no bridges connected it with the mainland so travel across the sound was by boat.

Wilbur traveled by train from Dayton to Elizabeth City, N.C., the nearest railroad point to his destination. Asking the first persons he chanced to meet about Kitty Hawk he learned that "no one seemed to know anything about the place or how to get there." Those better informed had vexing information: the boat making weekly trips to the Outer Banks had gone the day before. For several days he patiently waited to be dubiously rewarded by passage with Israel Perry on a flat-bottom fishing schooner, then anchored 3 miles down the Pasquotank River from the wharf at Elizabeth City.

The small skiff used to take Wilbur from the wharf out to the anchored schooner was loaded almost to the gunwale with three men and supplies. Noticing that the skiff leaked badly, Wilbur asked if it was safe. "Oh," Perry assured him, "it's safer than the big boat." Even so, the schooner managed to sail down the Pasquotank River and through Albemarle Sound safely enough in the rough weather.

It was 9 o'clock the following night before the schooner reached the wharf at Kitty Hawk. Though hungry and aching from the strain of holding on while the schooner rolled and pitched, Wilbur did not go shore until the next morning.

Tom Tate, drumfish, and Wright 1900 glider. A familiar figure in camp, young Tom, on one occasion, was lifted into the air on the glider. |

Later, Orville joined Wilbur at Kitty Hawk where both brothers boarded and lodged with the family of William J. Tate until October 4, when they set up their own camp about half a mile away from the village. Native Outer Bankers showed only mild interest in the Wrights' hopes of flying, but they became excited when they learned that the brothers were keeping in their tent, as fuel for a newfangled gasoline cookstove, the first barrel of gasoline ever taken to the Kitty Hawk area. Fearing an explosion, local folk warily warned their children to keep well away from the brothers' tent. Orville was the cook while in camp; to Wilbur fell the dish-washing chore. Orville always felt that he had the better of the bargain.

The new glider was a double-decker with a span of about 17 feet, and a total lifting area of 165 square feet. Its weight with operator was 190 pounds. It cost $15 to make. The uprights were jointed to the top and bottom wings with flexible hinges, and the glider was trussed with steel wires laterally, but not in the fore-and-aft direction. The operator, lying prone on the lower wing to lessen head resistance, maintained lateral equilibrium by tightening a key wire which, in turn, tightened every other wire, applying twist to the wingtips. The glider had no tail. Its wing curvature was less than Lilienthal had used.

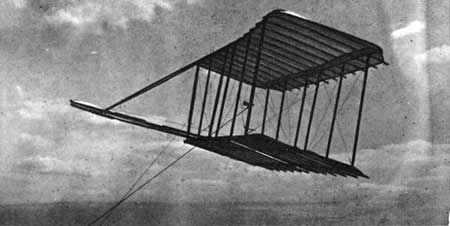

The 1900 glider flying as a kite.

Wilbur and Orville placed the horizontal operative rudder or elevator in front to provide longitudinal stability. They believed that by placing it in front they would have more up-and-down control to forestall nose dives similar to those that had killed Lilienthal and Pilcher. The Wrights did not invent the elevator. They did use it to more advantage than had earlier experimenters: it was in front of the wings; it was operative instead of fixed; and it flexed to present a convex surface to the air, instead of a flat surface.

The Wrights first flew the glider in the open as a kite. They held it with two ropes and operated the balancing system by cords from the ground. The first day's experiments were attempted with a man on board, using a derrick erected on a hill just south of their camp. The glider was not flown from the derrick again at Kitty Hawk after the first day's tests. On days when the wind was too light to support a man on the glider, they used chain for ballast or flew the machine as a kite in the open without ballast.

Before returning to Dayton, the brothers were determined to try gliding on the side of a hill with a man on board. Four miles south of their camp was a magnificient sand dune about 100 feet high, covering 26 acres, called Kill Devil Hill. They carried their glider to this hill where they made about a dozen free flights down its side.

To take-off from the hillside, one brother and an assistant holding the ends of the glider ran forward against the wind, while the brother who was to operate it ran with them until the machine began to "take hold" of the air, or was airborne. Then the operator jumped aboard and glided free down the hill for 300 or 400 feet, usually gliding only 3 or 4 feet above the soft, sandy ground. The Wrights repeatedly made landings on sledlike skids while moving at a speed of more than 20 miles an hour. The glider was not damaged, nor did the brothers receive any injury. "The machine seemed a rather docile thing," Orville wrote to his sister, from Kitty Hawk, "and we taught it to behave fairly well."

The brothers spent 3 days repairing the 1900 glider, wrecked by wind

on Oct. 10, 1900.

Wilbur and Orville had misread the weather charts they had studied when choosing Kitty Hawk as the location for their experiments. The charts had listed monthly averages, while the day-by-day weather proved to be less than ideal. On some days tests could not be made because of a dead calm; other days the wind blew too strong—up to 45 miles an hour. Orville wrote about the strong winds that blew:

A little excitement once in a while is not undesirable, but every night, especially when you are so sleepy, it becomes a little monotonous. . . . About two or three nights a week we have to crawl up at ten or eleven o'clock to hold the tent down. . . . We certainly can't complain of the place. We came down here for wind and sand, and we have got them.

Fellow campers at Kill Devil Hills, August 1901. From left: E. C.

Huffaker, Octave Chanute, Wilbur Wright, George Spratt.

Even though the Wrights had only brief spells of favorable weather for practice, they learned much from their experiments. They were pleased with the efficiency of wing-warping to obtain lateral balance, and the horizontal rudder for fore-and-aft control worked better than they had expected. Though Wilbur and Orville believed that fore-and-aft balance and lateral balance were equally important, they were gratified that fore-and-aft balance was so easily attained. They made careful measurements of lift, drag, and angle of attack. The main defect of the glider was its inadequate lifting power. This might be due, the brothers conjectured, to insufficient curvature or camber of the wings which did not have the curvature used by Lilienthal, or perhaps even the Lilienthal tables of air pressure might be in error.

Although important strides had been made toward solving the problem of control, Wilbur and Orville lacked opportunity for sufficient practice since they did not get much time in the air. There still remained much for them to learn before solving the major problems of how to (1) design wings properly, (2) control the aircraft in flight, and (3) provide power, in order to build and fly a powered machine. They knew that they must learn how properly to build and control a glider before attempting to add a motor. "When once a machine is under proper control under all conditions," Wilbur wrote his father from camp, "the motor problem will be quickly solved. A failure of motor will then mean simply a slow descent & safe landing instead of a disastrous fall." They looked forward to the next slack season in the bicycle business so that they might resume experiments with a new glider.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |