|

WRIGHT BROTHERS National Memorial |

|

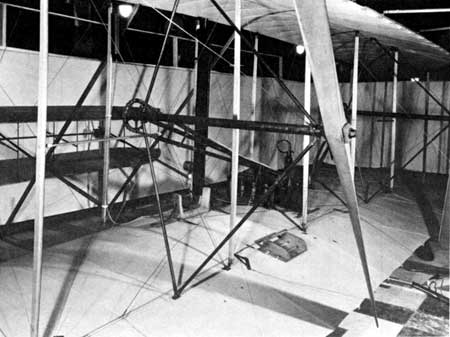

Wright 1903 machine (rear view) in the Smithsonian Institution showing

attachments on the lower wing.

Courtesy, Smithsonian

Institution.

The Powered Machine, 1903

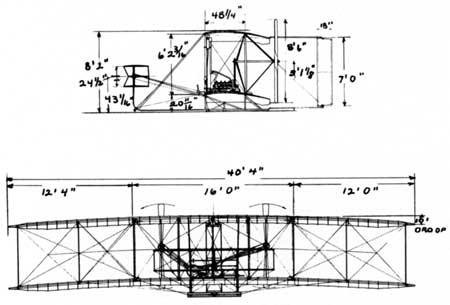

The 1903 machine had a wingspan of 40 feet, 4 inches; a camber of 1 in 20; a wing area of 510 square feet; and a length of 21 feet, 1 inch. It weighed 605 pounds without a pilot. The machine was not symmetrical from side to side; the engine was placed on the lower wing to the right of center to reduce the danger of its falling on the pilot. The pilot would ride lying prone as on the gliders, but to the left of center to balance the weight. The right wing was approximately 4 inches longer than the left to provide additional lift to compensate for the engine which weighed 34 pounds more than the pilot.

Fore-and-aft control was by means of the elevator in front, operated by hand lever. The tail of the machine had twin movable rudders instead of a single movable rudder developed in the 1902 glider. These rudders were linked by wires to the wing-warping system. Their coordinated control mechanism was worked by wires attached to a cradle on the lower wing, in which the pilot lay prone. To turn the machine to the left, the pilot moved his body, and with it the cradle, a few inches to the left. This caused the rear right wingtips to be pulled down or warped (thus giving more lift and raising them) and the rear left wingtips to move upward, and at the same time the coordinating mechanism introduced enough left rudder to compensate for yaw. The rudder counteracted the added resistance of the wing with the greater angle and the resulting tendency of the machine to swing in the opposite direction to the desired left turn as well as aiding the turn on its own account.

Plans of the Wright Brothers 1903 plane and photographs

of front and side views of the plane.

Plans, courtesy, Smithsonian

Institution.

On September 25, 1903, the Wrights arrived once more at their Kill Devil Hills camp. They repaired and again used the living quarters which they had added to the storage building in 1902, called their "summer house." Their 1902 glider, which they had left stored in this building after that season of experiments, was again housed with them in the building. They erected a new building to house the powered machine alongside the glider-storage and living quarters building and commenced the chore of assembling the powered machine in its new hangar. Occasionally they took the 1902 glider our for practice. After a few trials each brother was able to make a new world's record by gliding for more than a minute.

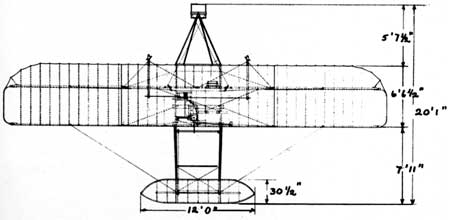

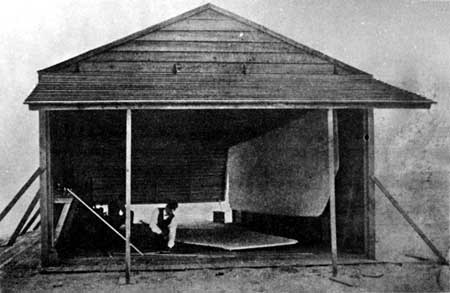

Assembling the 1903 machine in the new camp building at Kill Devil

Hills, October 1903.

The first weeks in camp were a time of vicissitudes for the Wrights. Assembling the machine and installing the engine and propellers proved an arduous task. When tested, the motor missed so often that the vibrations twisted one of the propeller shafts and jerked the assembly apart. Both shafts had to be sent back to their Dayton bicycle shop to be made stronger. After they had been returned, one broke again, and Orville had to carry the shafts back to Dayton to make new ones of more durable material. The magneto failed to produce a strong enough spark. A stubborn problem was fastening the sprockets to the propeller shafts; the sprockets and the nuts loosened within a few seconds even when they were tightened with a 6-foot lever.

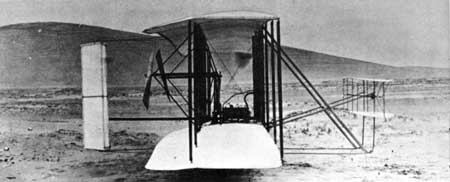

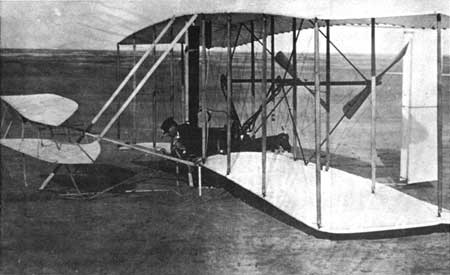

The 1903 machine and camp buildings at Kill Devil Hills, Nov. 24, 1903.

It was then that the weather acted as if it were threatening the brothers not to venture into a new element. A gale swept over their camp with winds up to 75 miles an hour. As their living quarters rocked with the wind, and rainwater flowed over part of the floor, the Wrights expected to hear the new hangar building next door, which housed the powered machine, crash over completely. "The wind and rain continued through the night," related Wilbur to his sister, "but we took the advice of the Oberlin coach, 'Cheer up, boys, there is no hope,' We went to bed, and both slept soundly."

It became so cold that the brothers had to make a heater from a drum used to hold carbide. Wilbur assured his father:

However we are entirely comfortable, and have no trouble keeping warm at nights. In addition to the classifications of last year, to wit, 1, 2, 3, and 4 blanket nights, we now have 5 blanket nights, & 5 blankets & 2 quilts. Next come 5 blankets, 2 quilts & fire; then 5, 2, fire, & hot-water jug. This as far as we have got so far.

At last the weather cleared, the engine began to purr, their handmade heater functioned better after improvements, and, with the help of a tire cement they had used in their bicycle shop, they "stuck those sprockets so tight I doubt whether they will ever come loose again." Chanute visited their camp for a few days and wrote November 23, "I believe the new machine of the Wrights to be the most promising attempt at flight that has yet been made." Both brothers sensed that the goal was in sight.

The powered machine's undercarriage (landing gear) consisted of two runners, or sledlike skids, instead of wheels. These were extended farther out in front of the wings than were the landing skids on the gliders to guard against the machine rolling over in landing. Four feet, eight inches apart, the two runners were ideal for landing as skids on the soft beach sands. But for take-offs, it was necessary to build a single-rail starting track 60 feet long on which ran a small truck which held the machine about 8 inches off the ground. The easily movable starting rail was constructed of four 15-foot 2 x 4's set on edge, with the upper surface topped by a thin strip of metal.

The truck which supported the skids of the plane during the takeoff consisted of two parts: a crossbeam plank about 6 feet long laid across a smaller piece of wood forming the truck's undercarriage which moved along the track on two rollers made from modified bicycle hubs. For take-offs, the machine was lifted onto the truck with the plane's undercarriage skids resting on the two opposite ends of the crossbeam. A modified bicycle hub was attached to the forward crosspiece of the plane between its skids to prevent the machine from nosing over on the launching track. A wire from the truck attached to the end of the starting track held the plane back while the engine was warmed up. Then the restraining wire was released by the pilot. The airplane, riding on the truck, started forward along the rail. If all went well, the machine was airborne and hence lifted off the truck before reaching the end of the starting track; while the truck, remaining on the track, continued on and ran off the rail.

With the new propeller shafts installed, the powered machine was ready for its first testing on December 12. However, the wind was too light for the machine to take-off from the level ground near their camp with a run of only 60 feet permitted by the starting track. Nor did they have enough time before dark to take the machine to one of the nearby Kill Devil Hills, where, by placing the track on a steeply inclined slope, enough speed could be promptly attained for starting in calm air. The following day was Sunday, which the brothers spent resting and reading, hoping for suitable weather for flying the next day so that they could be home by Christmas.

On December 14 it was again too calm to permit a start from level ground near the camp. The Wrights, therefore, decided to take the machine to the north side of Kill Devil Hill about a quarter of a mile away to make their first attempt to fly in a power-driven machine. They had arranged to signal nearby life-savers to inform them when the first trial was ready to start. A signal was placed on one of the camp buildings that could be seen by personnel on duty about a mile away at the Kill Devil Hills Life Saving Station.

The first Wright Flyer rests on the starting track

at Kill Devil Hill prior to the trial of Dec. 14, 1903. The four men

from the Kill Devil Hills Life Saving Station helped move the machine

from the campsite to the bill. The two boys ran home on hearing the

engine start.

The Wrights were soon joined by five lifesavers who helped to transport the machine from camp to Kill Devil Hill. Setting the 605-pound machine on the truck atop the starting track, they ran the truck to the end of the track and added the rear section of the track to the front end. By relaying sections of the track, the machine rode on the truck to the site chosen for the test, 150 feet up the side of the hill.

The truck, with the machine thereon, facing downhill, was fastened with a wire to the end of the starting track, so that it could not start until released by the pilot. The engine was started to make sure it was in proper condition. Two small boys, with a dog, who had come with the lifesavers, "made a hurried departure over the hill for home on hearing the engine start." Each brother was eager for the chance to make the first trial, so a coin was tossed to determine which of them it should be; Wilbur won.

Wilbur Wright in damaged machine near the base of Kill Devil Hill

after unsuccessful trial of Dec. 14, 1903. Repairs were completed by

the afternoon of December 16, but poor wind conditions prevented another trial until the following

day.

Wilbur took his place as pilot while Orville held a wing to steady the machine during the run on the track. The restraining wire was released, the machine started forward quickly on the rail, leaving Orville behind. After a run of 35 or 40 feet, the airplane took off. Wilbur turned the machine up too suddenly after leaving the track, before it had gained enough speed. It climbed a few feet, stalled, and settled to the ground at the foot of the hill after being in the air just 3-1/2 seconds. This trial was considered unsuccessful because the machine landed at a point at the base of the hill many feet lower than that from which it had started on the side of the hill. Wilbur wrote of his trial:

However the real trouble was an error in judgment, in turning up too suddenly after leaving the track, and as the machine had barely speed enough for support already, this slowed it down so much that before I could correct the error, the machine began to come down, though turned up at a big angle. Toward the end it began to speed up again but it was too late, and it struck the ground while moving a little to one side, due to wind and a rather bad start.

In landing, one of the skids and several other parts were broken preventing a second attempt that day. Repairs were completed by noon of the 16th, but the wind was too calm to fly the machine that afternoon. The brothers, however were confident of soon making a successful flight. "There is now no question of final success," Wilbur wrote his father, though Langley had recently made two attempts to fly and had failed in both. "This did not disturb or hurry us in the least," Orville commented on Langley's attempts. "We knew that he had to have better scientific data than was contained in his published works to successfully build a man-carrying flying machine."

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |