|

FORT UNION National Monument |

|

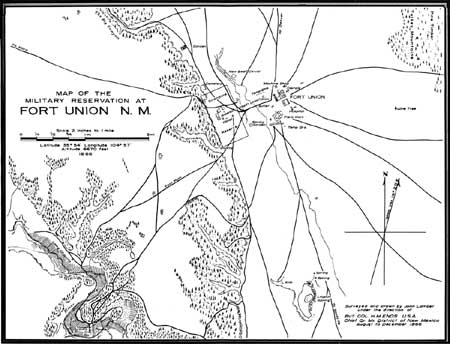

(click image for an enlargement in a new window)

A New Fort

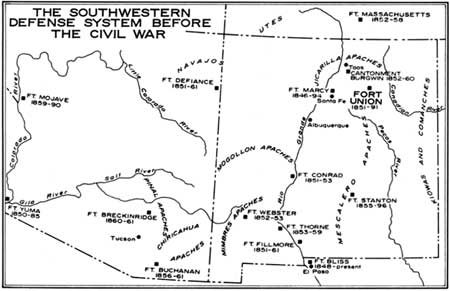

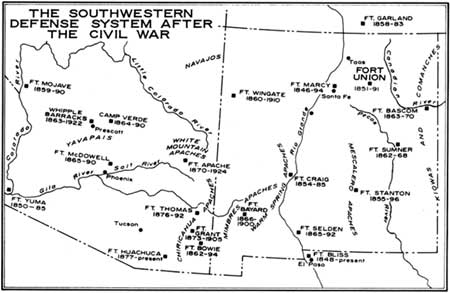

Sibley's departure coincided with the arrival of fresh troops. California had responded to Canby's appeal for help in the defense of New Mexico by rushing a brigade of volunteers across the deserts of southern Arizona. The "California Column," Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton commanding, reached Mesilla in July 1862, too late to help drive the Confederates out of the territory. The Colorado Volunteers went home to fight Indians, and the California Volunteers stayed in New Mexico to fight Indians. On September 17, 1862, Canby turned over command of the Department of New Mexico to General Carleton and left for a new assignment in the East.

Carleton had served as a dragoon captain under Colonel Sumner at Fort Union in 1851 and 1852. Now he turned his attention once more to his old station. For years it had been regarded as an undesirable assignment. Inspecting officers had recommended that it be entirely rebuilt, or moved to the vicinity of Alexander Barclay's trading post at the junction of the Mora and Sapello Rivers, or abandoned altogether. In November 1862 Carleton gave orders to begin work on a new fort at the old location.

(click image for an enlargement in a new window)

(click image for an enlargement in a new window)

The sprawling installation that took shape was the largest in New Mexico and required 6 years, 1863 to 1869, to complete. Actually, it was three installations in one—the Post of Fort Union, the Fort Union Quartermaster Depot, and the Fort Union Ordnance Depot. The post and quartermaster depot were built next to each other on the valley floor northeast of the star fort. The ordnance depot rose on the site of the old log fort at the western edge of the valley.

The new buildings stood in sharp contrast to the old. Designed in the boxlike "territorial" style of architecture that came to be distinctive of New Mexico, they were constructed of native building materials. The walls were of adobe brick, moulded from soil dug from the valley north of the fort. They stood on stone foundations and as protection against moisture were coated with plaster fired in limekilns south of the fort and surmounted by copings of bricks manufactured in Las Vegas. At first, dressed lumber for the woodwork came from Ceran St. Vrain's sawmill at the town of Mora and from two mills on the Sapello River. Later the Army acquired its own planing mill, and logs cut from the Fort Union timber reserve in the Turkey Mountains were dressed at the fort. Such items as tools, nails, window glass, fire bricks, and roofing tin had to be hauled over the Santa Fe Trail from Fort Leavenworth.

The Post of Fort Union was laid our to accommodate four companies—cavalry, infantry, or a combination of both. The nine houses that made up officers' row lined a spacious parade ground on the west. In the center of the line stood the commanding officer's home. Flanking it on either side were four houses, each divided by a wide hall into apartments for two families. Across the parade ground to the east were four sets of barracks for enlisted men. Behind the barracks were quarters for laundresses and married soldiers, administrative offices, bakery, prison, guardhouse, chapel, storehouses, and corrals with wooden stables for 200 horses. Just south of this complex of buildings stood the 36-bed hospital, which served all the personnel at Fort Union.

The parade ground extended north into the Fort Union Quartermaster Depot, which supplied all the New Mexico forts. In line with the post officers' quarters were the depot officers' quarters and administrative offices. Across the parade ground, in line with the post barracks, were four large storehouses and the mechanics' corral, which consisted of shops and quarters for blacksmiths, carpenters, and wheelwrights. Behind this group of buildings was the transportation corral, with sheds for freight wagons, storage houses for grain, and quarters for the teamsters. As the Army supply center for all New Mexico, the Fort Union depot boasted a much larger physical plant than the post of Fort Union, and it employed considerably more men, mostly civilians.

Fort Union, as it is and as it was.

By comparison, the Fort Union Arsenal, which served the ordnance needs of the department, was a modest establishment. It consisted of an officer's house, a barracks building, storehouses, shops, and magazine, all surrounded by a wall 4,000 feet square. Capt. William R. Shoemaker, who had been at Fort Union since Colonel Sumner's time, presided over this part of the fort.

Water for all three units of the fort came from wells and storage cisterns spotted among the buildings. All the buildings were heated by fireplaces and lighted by spacious windows by day and candles or oil lamps by night.

Fine as the elaborate new Fort Union appeared, it too had been hastily constructed. The main trouble lay in faulty roofing, which admitted water to the adobe walls and started an eroding action that made repairs constantly necessary. There were those, too, who questioned its utility for any purpose. Among them was Lt. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, a very important person indeed, who wrote in 1869 that Fort Union "has grown into proportions which never at any time were warranted by the wants of the public service. Quartermasters and Commanding Officers have gone on increasing and building up an unnecessary post, until it has become, by the unnecessary waste of public money, an eye sore. I do not accord with the opinion of anyone as to its military bearings for protection of field operations, nor do I see any necessity for it as a Depot." Necessary or not, Fort Union continued to grow for an other 20 years and to serve as a tactical base and supply depot on the New Mexico frontier.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |