|

AZTEC RUINS National Monument |

|

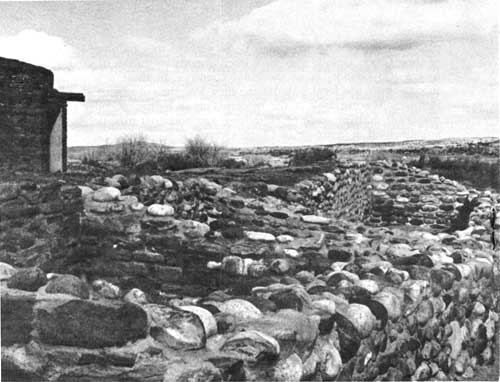

Cobblestone walls at Aztec Ruins.

Man in the San Juan Valley

THE AZTEC PUEBLO. (continued) But there is a double mystery at Aztec: as indicated earlier, overlying the evidences of a Chaco-phase occupation, Morris found evidence of rebuilding and rehabitation of many rooms. Large-sized Chaco rooms had been shortened, reduced, or cut off by interior walls and lowered ceilings. Older doorways had been blocked up, or had been partially filled and reduced in size. In some cases entire small rooms, complete with ceilings, had been built within larger rooms. New floors had been laid down upon the debris and windblown sand which partially filled some of the older rooms. Older beams had been pulled out of rooms and reused elsewhere or new walls in a different style had been built in place of those that had collapsed.

A newer style of pottery, reminiscent of the Mesa Verde-type pottery, was prevalent. The majority of burials found within the ruins, 149 out of a total of 186, seemed to belong to a different period as shown by the type of artifacts associated with them. T-shaped doorways, an architectural trait characteristic of Mesa Verde times, was prevalent in the later parts of the pueblo. Keyhole-shaped kivas, another Mesa Verde trait, were inserted into and between rooms of the earlier period. And finally, the Great Kiva in the central plaza, which had fallen into disuse, was rehabilitated—in a much poorer style of construction, surely, but nonetheless obviously repaired and temporarily put back into use.

These factors inclined Morris to feel that some time after A.D. 1124 the pueblo at Aztec was abandoned by the Chacoan builders. Then about 1225, a new group arrived, bringing with them the general styles and culture of the area we know as Mesa Verde.

As with the earlier occupation at Aztec, we do not know exactly who these second people were or exactly where they came from, although it is obvious that they had a close affiliation with the people of the Mesa Verde area. Nor do we know if they were a large group, representing a mass migration, or whether once again some of the local population may have decided to attempt building a large community. Perhaps for a second time a few people, possessing special abilities or representing a religious organization, prevailed upon either the local population of the Animas Valley or wandering migrant groups to assist them in erecting large community structures.

We do know that at about this time there was a considerable population shift all over the Mesa Verde area. The people were dispersing from their normal habitats and moving into more protected locations or consolidating into larger, more defensible units. In the Mesa Verde itself, for example, they were abandoning their mesatop pueblos and crowding together in the caves or moving out of the area entirely. In the Hovenweep area, they retreated to the heads of the canyons and built watchtowers along the canyon sides and bottoms to protect their dwindling water supplies. It was evidently a period of considerable strife and turmoil. There were short periods of recurrent drought, and possibly many of these groups had begun to fight among themselves over land and water rights and other necessities of life.

The second occupation at Aztec was more intensive and one in which parts of the local population participated actively. The construction style of this period shows a considerable use of local cobblestones set in adobe mortar, as in many of the small ruins throughout the Animas. Sometimes cobblestone walls are overlaid or underlaid by, or even intermingled with, sandstone walls. It was at this time also, as far as we know, that the other pueblo units—now all ruins—within the monument boundary were constructed, as well as several other major Mesa Verde-phase structures elsewhere in the Animas Valley.

In addition, large quantities of new material had to be secured fairly rapidly to keep pace with the feverish building activities at Aztec. While some of the rooms of the large Chaco-style pueblo were rehabilitated by these new inhabitants, others were dismantled and their materials, in addition to those from fallen walls, were used elsewhere. But even this great pueblo could not supply all the stone needed. So from the old quarry to the site of the pueblo two paths were built, side by side, each wide enough for eight men to walk abreast. For many months, men with stone mauls and hammers cracked and chopped and ground the sandstone into building blocks. Other men and the stronger boys toiled all day in straggling lines, carrying the blocks on large wooden litters or in great slings strung on poles. Long lines of workers streamed down one path, loaded with blocks, to return over the other path with their empty litters and slings.

Although the Great Kiva was repaired, with rather sloppy workmanship in many places, it was probably only used for a brief period. The focal point of the community's religious life seems to have centered around the peculiar and somewhat puzzling tri-wall structures, two of which exist at Aztec. One is the excavated Hubbard Mound site just to the northwest of the main ruin; the other is Mound F, which is also to the northwest of the other major but largely unexcavated ruin—the East Ruin. If there was such a thing at this time as the beginning of a priestly hierarchy among the Pueblo peoples, these tri-wall structures with their centralized kivas may have been the domiciles and religious quarters of this hierarchy.

Once again life seemed to flourish at Aztec. This time with all the extra pueblo units close to each other, the area must have resembled a veritable beehive. It would have taken an extensive farming area to support the population. If a shift in the river had cut the Chacoans' canal, another shift back again may have made it possible to restore the old canal, improve it, and once again make the surrounding fields green in summer with growing corn, beans, squash, and cotton.

In contrast to the Chacoan occupation, Morris found a large number of burials (149) from this period, mostly in the rooms. Many were buried with great care and had numerous and varied grave offerings. For a while, evidently, the Pueblos prospered and traded far and wide for luxury items. But once again bad times set in, possibly accompanied by almost constant armed harassment by less fortunate groups. Although Morris did not find any direct evidence that the people at Aztec were actually killed off or driven out by armed conflict, the later burials were all hastily made and usually unaccompanied by grave offerings. In addition, almost the entire east wing had been destroyed by fire. This could have been accidental and such a disaster might have proven the final straw for an already beleaguered group; or they may have fired the pueblo before leaving, or some marauding group might have been responsible.

The photo in the original handbook

pictured human remains. Out of respect to the Pueblo descendants of the

people who lived at Aztec Ruins, the depiction of human remains and

funerary objects will not be displayed in the online edition.

An Aztec Ruins burial with pottery mug in situ.

Exactly why, after 25 or 30 years, the second group also abandoned the site we may never know. Times were hard in the Four Corners country, and by 1300 this area seems to have been virtually depopulated. Perhaps the abandonment of Aztec, sometime after 1252, was simply a local manifestation of this much larger dispersal.

No doubt the great drought of the last quarter of that century contributed substantially to this general abandonment, but there must have been other factors at work as well. The Indians regard the forces of nature in a different manner than we do. They may have been struggling through long years, not only with nature but among themselves. They may have felt that their gods were against them, that somehow they had offended them, and that nothing they could do in that country would be right again. It may have seemed easier to them, family by family, group by group, and perhaps pueblo by pueblo, to give up the struggle and go elsewhere, to start over in new surroundings where the gods might smile upon them once again.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Tues, Feb 20 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT |