|

AZTEC RUINS National Monument |

|

The Earl Morris house about 1933; today the Aztec Ruins Visitor

Center.

Explorations and Excavations (continued)

The name of Earl H. Morris is well known in Southwestern archeology. Although he also did considerable archeological work in Central America, particularly at the Temple of the Warriors at Chichen Itza in Yucatan, trying to unravel the story of the prehistoric inhabitants of the American Southwest was always his first love. Morris was born on October 24, 1889, in Chama, N. Mex. His family had originally come west from the Pennsylvania oil fields in the mid-1870's, and his father engaged in construction work such as building railway grades and roads, digging canals, and hauling freight. In 1891, the elder Morris moved his family to Farmington, N. Mex. There, he was able to rent out his teams on a canal construction project. This left him free to pursue his hobby—digging for Indian antiquities—the love of which he was able to impart to his son Earl.

When Earl was 3-1/2 years old he actually excavated his first Indian pot. As he used to tell it:

One morning in March of 1893, Father handed me a worn-out pick, the handle of which he had shortened to my length, and said: "Go dig in that hole where I worked yesterday, and you will be out of my way." At my first stroke there rolled down a roundish, gray object that looked like a cobblestone, but when I turned it over it proved to be the bowl of a black-on-white dipper. I ran to show it to my mother. She grabbed the kitchen butcher knife and hastened to the pit to uncover the skeleton with which it had been buried. Thus, at three and a half years of age there had happened the clinching event that was to make of me an ardent pot hunter, who later on was to acquire the more creditable, and I hope earned, classification as an archaeologist.

Morris' father was killed when he was 15, and he had to go to work to support his mother and to put himself through school and college as well. In 1908, he entered the University of Colorado, but he left temporarily to join an archeological expedition to the Maya country of Guatemala. Later he returned to college and received his B.A. in 1914 and his M.A. in 1916.

Having spent the winter of 1915 in New York City at Columbia University, Morris was well acquainted with the leading archeologists at the American Museum of Natural History. It was, therefore, upon Dr. Nelson's recommendation that the ruins at Aztec would make an excellent subject for intensive study by the museum, that Morris was hired to conduct the investigations. He was in charge of the Aztec excavations from 1916-21, and sporadically through 1923, at which time the area became a National Monument. Morris was the first custodian, as they were called in those days, and was officially appointed on February 8, 1923, at the salary of $12 per annum.

He not only excavated the major part of the West Ruin very carefully, but also stabilized and repaired the walls as he went along, for the museum greatly desired that this ruin might be preserved as an outstanding monument. Later, in 1933-34, Morris' services were loaned to the National Park Service by the Carnegie Institution so that he might accurately restore and reroof the Great Kiva at Aztec.

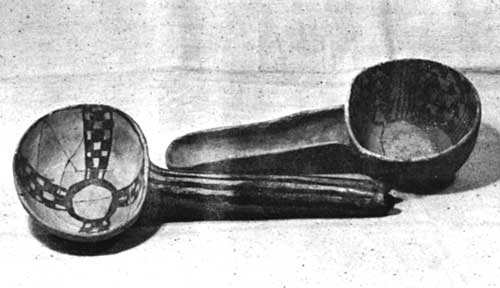

Mesa Verde-style pottery mugs. LEFT MUG: Diameter at bulge, 4-1/3";

Diameter at mouth, 3"; Height; 4-1/4". RIGHT MUG: Diameter at bulge,

4-1/3"; Diameter at mouth, 3"; Height, 4-1/4".

Morris dug in a number of other places throughout the Southwest in addition to Aztec and therefore was in a better position than any other man of his time to interpret and explain the development of the prehistoric cultures in the Four Corners country. He produced a number of valuable archeological reports, most of them under the auspices of the Carnegie Institution for which he worked for many years. With his death in 1956, Southwestern archeology suffered a severe loss, for there are not many scientific investigators with both his skill and motivation. As his lifelong friend A. V. Kidder has said about him:

Throughout his career, Morris was doubly motivated. First, of course, by the urge to trace the course and discern the causes of historical events and cultural developments. Secondly, by an exceptionally ardent wish to make evident to the world of today the achievements of the past. Back of this was his own admiration for and striving to preserve all ancient things that were beautifully and soundly made. I think he may also have felt, perhaps subconsciously, an obligation to repay, by rescuing their work from oblivion, the men and women of long ago whose artistry and manual skills gave him such keen and lasting pleasure.

Digging in ruins such as at Aztec, where a dry climate has helped preserve many perishable items normally lost to archeologists and where there was always the opportunity of suddenly discovering a fairly complete and undisturbed room, must have been a stimulating experience to a man of Morris' capabilities. One has only to browse through his reports and articles, or to glance at the pictures therein, to get the feeling of intense excitement about each discovery that prevailed throughout the 5 years he was digging there. It would be impossible to describe everything that Morris excavated, but several of the burials that he uncovered were of exceptional interest.

Pottery ladles from Aztec Ruins, LEFT LADLE:

Diameter of bowl, 4-1/4"; Handle length, 12-1/2"; Height, 2-1/4". RIGHT

LADLE: Diameter of bowl, 5"; Handle length, 6-3/4"; Height,

2-1/2".

One consists of what may be the only known case of prehistoric Pueblo surgery. In one of the rooms Morris found the remains of a young female 17 to 20 years of age accompanied by several bowls and a pottery mug. The body had been wrapped in an excellently woven cotton cloth, which in turn, had been covered by a mantle of feather cloth and finally, with a mat of plaited rushes. The young lady had been seriously injured, perhaps in a fall, for the hip had been severely fractured, several vertebrae cracked, and both bones of the left forearm badly broken. But what was of particular interest, was that an attempt had been made to treat the broken arm. Six wooden splints, each flat on one side and convex on the other, had been bound in longitudinal position around the arm. As Morris said, if the Indians who attempted to help this girl realized that her pelvis was also broken they were unable to do anything about that, but evidently they had attempted to set the arm and return it to normal. Unfortunately, death occurred before sufficient time had elapsed to permit the healing to begin, so we do not know how successful this sort of treatment might have been. Although the surgery may seem crude and bungling to at least it shows an awareness of what was wrong and an attempt to correct it.

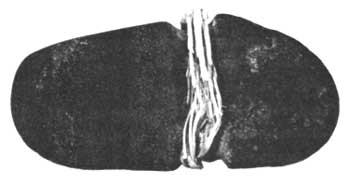

Full-grooved ax with fragment of hafting material.

Length, 7"; Maximum width, 3-1/2"; Width at groove,

2-3/4".

Another fascinating burial was the one which Morris referred to as the "warrior's grave", in which he found an adult male buried in a grave-pit sunk into the floor of a room. A wrapping of feather cloth enveloped the entire body, and there had been an equally extensive outer covering of rush matting. Along with numerous other grave offerings of artifacts and pottery vessels, a large, ornate shield was laid over the body. It consisted of a flat piece of coiled basketry 36 inches long and 31 inches wide, and on one side was lashed a hardwood handle. The outermost 5 coils of the shield had been coated with pitch and thickly spangled with minute flakes of selenite; the next 5 were stained dark red, while the remaining 48 were greenish-blue. In addition to the shield there were axes of a form intermediate between axes and hammers so that it would appear they were intended for use as weapons rather than tools. One is beautifully fashioned from a piece of hematite or similar iron ore, and both had wooden handles which lay near the right hand of the body. Near the left hand was a long knife of red quartzite, positioned so that it might have been inserted in a belt or girdle. Also beside the body was a long, thin, tapering wooden object which might have been interpreted as a digging stick but which Morris felt would also have been serviceable as a sword.

It is not often an archeologist has an opportunity to uncover spectacular remains of this sort, but these are only two of the fascinating burials which Morris recovered from the Aztec ruins. In all he found 186 interments. Strangely enough, only 6, with possibly 2 others, could be identified as belonging to the Chacoan phase at Aztec; 149 were definitely of the Mesa Verde period, 12 others probably so, and 17 were found in circumstances which made it impossible to tell to which period they belonged.

But burials were not the only things which Morris uncovered. He began his diggings in the southeast corner of the ruin, excavating the entire east wing from south to north. The problem of moving the dirt, debris, and fallen rocks was considerable, especially when he did not want merely to pile it off to one side where he might subsequently have to move it a second time. Furthermore, the ruin was to be stabilized as a permanent monument, so it was necessary to remove the debris well outside the ruin area. At one time he evidently considered building a sluiceway from an irrigation ditch which runs along a higher level on the north side of the ruin, thinking that most of the debris could be dumped in the sluice box and washed out to a lower area by the river. Perhaps this scheme did not prove to be feasible, for instead, during the first season's excavations, he constructed a narrow-gage tramway on which the workmen ran dump cars. Unfortunately, this method of dirt removal did not work satisfactorily either, because the relatively light rails which were used would not support the weight of the loaded dump trucks. He also had difficulty with the size and quality of the wheels on the dumpcarts. Although excavators elsewhere have sometimes used this method of removing dirt, it frequently presents its own type of engineering problems. In the remaining years of the work at Aztec, Morris employed horse-drawn carts which could be loaded directly from the excavations and hauled to a vacant area to be dumped.

Early "diggings" at Aztec Ruins.

In many places the digging was extremely laborious, for over the centuries the dirt and debris had been packed into a consistency almost like that of concrete. In other places the rooms were full of all sorts of prehistoric rubbish, intermixed with broken artifacts which had to be carefully sorted out. In describing the excavations in one room Morris said:

The ceiling failed in the most unusual way, the supports having been broken first at the center, then at each end, where they entered the wall. The small poles seemed to have parted from the walls almost as soon as the center timbers gave way. Some were standing upright against the end walls, while the majority were mashed back against and along the east wall. The splints, bark, and adobe were in a grievous tangle, most difficult to excavate. Above the first ceiling were decayed, but unburned, timbers and lumps of charcoal and reddened earth representing, respectively, the second and third ceilings.

Morris completely excavated the east wing and the eastern half of the north wing. In addition he also excavated 29 rooms in the west wing and about two-thirds of the small cobblestone 1-story rooms which close off the southern third of the plaza area.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jan 13 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |