|

AZTEC RUINS National Monument |

|

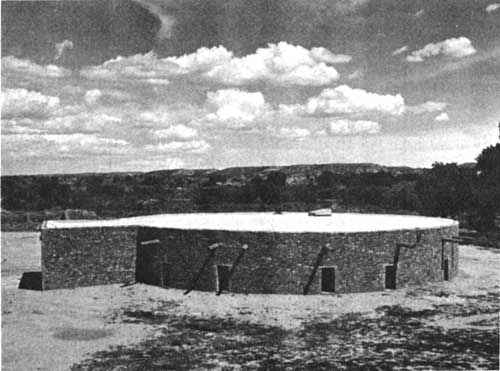

Exterior of the reconstructed Great Kiva.

Explorations and Excavations (continued)

Besides excavating many of the kivas enclosed within the pueblo rooms, Morris also excavated the large Chaco-like kiva in front of the northeast corner, as well as the Great Kiva which is centrally located on the south side of the plaza. Later, in 1933 and 1934, Morris returned to Aztec and supervised the stabilization and reconstruction of this Great Kiva, so that today you see it as it supposedly existed when the Indians used it for ceremonial purposes.

Immediately to the west of the main ruin, where the brush had been cleared, Morris found a rather extensive low mound area.

The surface was an orderless succession of hummocks and depressions, the former thickly strewn with cobblestones, the whole presenting an appearance characteristic of most of the ruins in this end of the valley.

Thinking these might be the remains of an earlier structure, he excavated most of it. To his surprise, the reverse proved to be true. Although there had undoubtedly been an earlier Chaco-like sandstone structure at this point, most of it had been torn down and the debris carried elsewhere or utilized in building the great ruin itself. Morris said:

Overlying the earliest remains there are deposits of clean earth, some of it presumably laid down by the elements, but the bulk of it is excavated earth intentionally dumped where it lies.

At some later date, the Mesa Verde-like people had built cobblestone houses, pit rooms, and small kivas on top of this earlier debris. Today the outline of some of these cobblestone walls can be seen on the ground just to the left of the visitor trail as it proceeds northward to enter the main part of the West Ruin.

Since Morris' excavations at Aztec, there has been sporadic digging, much of it in connection with the Service's ruins stabilization program. To prevent soil moisture from seeping into the lower footings of these ancient walls, it is frequently necessary to dig down to their bases and cap them with concrete or preserve them by other suitable methods. In doing so, old refuse pits, broken fragments of pottery, or even a burial is occasionally turned up.

Recently, in making excavations in which to place dry barrels for drainage purposes in two rooms on the east side, two interesting ovenlike structures, each exactly centered in a room, were accidentally found. Their location in adjoining rooms, and their central position in the rooms, precludes the possibility that they were pit ovens from an earlier period before the pueblo was built. Doubtless they had been placed deliberately in these two rooms, and they may have been used for roasting large quantities of corn or preparing certain types of baked cornmeal or cornbread.

Also since Morris' time, the rooms through which you may now pass, and which lie between the plaza proper and the rooms with the intact ceilings, have been partially excavated in order to allow you easier access to the plaza. Finally, as part of the stabilization program, the remaining rooms in the south wing which enclosed the plaza, and which were largely composed of cobblestones, were cleared and stabilized.

Morris also excavated a few rooms in the East Ruin simply as a test to see if it belonged to the same general period as the larger ruin in the west. From his findings there he felt that the East Ruin was erected during the Mesa Verde phase of Aztec.

In recent years, one other major excavation has been undertaken at Aztec, This was the complete clearing and stabilization of the circular structure to the north of the ruin known as the Hubbard Mound—a massive, circular, triple-walled structure, with underlying scattered remains of earlier structures. Two heavy radial cobblestone walls now extend to the south of the main structure, and excavations revealed remnants of other heavy walls disappearing under the road to the west. This indicates that the building had originally been one corner of a group of structures. The main part of the Hubbard Mound consists of three concentric circular walls; the spaces between the outer two rings are partitioned into rooms. There are 8 rooms in the inner circle, including an entrance room on the south, and 14 in the outer, if you again count an open passageway on the south side.

Interestingly enough, the three circular walls are heavier and extend deeper into the underlying sand than do the partition walls, and therefore were constructed first as continuous circles. Within the innermost circle there is a standard, small-type kiva. Evidently the entire structure represents a building for the use of a highly specialized religious organization. Part of the construction is of sandstone blocks, part is cobblestone, and all of it seems to have been generously plastered with adobe mud.

There are other examples of tri-walled structures in the Southwest, but they are not very numerous and the exact uses to which they might have been put are unknown. An analysis of materials found during the excavation of the Hubbard Mound reveals that it belonged to the Mesa Verde phase.

When Morris first undertook the excavations at Aztec it was his intention, and that of the American Museum of Natural History, to excavate the ruins completely. However, the undertaking was a massive one. World War I intervened, with all its uncertainties, and funds frequently ran short. In the later days of the excavations, Morris realized there was an advantage to leaving parts of any ruin unexcavated so that better archeological techniques in the future might extract information of which he was unaware. At present, the National Park Service feels much the same way. Perhaps 25 or 50 years from now further excavations may be undertaken in this area, but for the present, the ruins will be left as they are, complete with their feeling of mystery.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jan 13 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |