|

AZTEC RUINS National Monument |

|

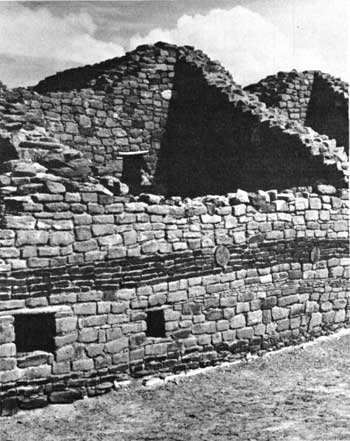

Section of wall at Aztec Ruins showing a band of

green sandstone.

The Aztec Ruins Today

Aztec Ruins National Monument consists of an enclosed area of 27 acres containing six major archeological complexes of rooms and structures, and at least seven or eight smaller mounds which may contain structures or may simply be trash and refuse mounds from the larger occupation zones. Two of these major complexes have been excavated: the West Ruin and the Hubbard Mound. Two of the others—the East Ruin and Mound F—have been tested. Mound F is evidently very similar to the Hubbard Mound.

The East Ruin, if excavated, might be similar in most respects to the West Ruin, both in appearance and time of occupation. As to whether the smaller mounds contain trash or house remains, only thorough archeological investigations can tell. Morris' diggings and subsequent small tests have indicated there may be earlier (Developmental Pueblo) remains underlying the main prehistoric complexes. Also, such remains might still be found under the windblown sand in the flatter areas between the major ruins. No real archeological work has ever been done in the monument area to determine the possible extent of such earlier remains.

Aztec Ruins during excavations of the

1920's.

The two main sites seen by the visitor to the monument are therefore, the West Ruin and the Hubbard Mound. The West Ruin was the one first entered by early settlers in the late 19th century. The profuse remains caused extensive digging and looting for about a decade. Then, under the ownership first of John R. Kuntz and later of H. D. Abrams, the area was given a certain amount of protection. During 1916-21, the American Museum of Natural History excavated extensively in the West Ruin under the guidance of Morris. Today, three-fourths of this ruin has been excavated, cleared, and stabilized so that you may gain a firsthand impression of its original appearance. The remaining one-fourth is largely unexcavated and, for all anyone knows, may contain archeological riches equal to any recovered in the early days or during the excavations by the American Museum of Natural History.

Although some of the rooms and walls seen by the first white settlers in the valley have now collapsed, evidence of at least three stories is still clearly visible in several places in the ruin. The main part consists of three sides of a rectangle with a slightly bowing outer wall on the fourth side, composed of single rooms, which seals off the central plaza. The only entrance into the pueblo was the one along the path by which visitors enter the ruin today.

The pueblo was built of yellowish-brown and tan sandstone blocks, most of them shaped into rectangles by pecking or grinding. To support the weight of the upper rooms, the lower walls are much thicker and are composed of rubble fill with an outer veneer wall of the better shaped rectangular blocks. In many places, the spaces between them are filled with small chinking stones set in adobe mud, Sometimes broken pieces of pottery vessels were used for spalls. Originally, the walls were plastered with layers of adobe, most of which, unfortunately, have eroded away.

One unusual feature in the West Ruin consists of two very fine bands of green sandstone blocks which extend horizontally along the west outer wall of the pueblo and into a few of the interior rooms of the southwest corner. There are indications in a few places that originally there may have been three such parallel bands.

The north and northwest sides of the ruin contain the most extensive building remains. The highest walls and best construction still exist there, and one can see evidence of at least three stories. Also in the north portion, along the extreme back row of rooms at the ground level, there is a series of seven rooms, each of which has its original ceiling intact. These seven were the first entered by early relic hunters, who found most of the original doorways to the south sealed up and who broke through the walls of each room in an easterly direction. These breaches in the walls have been repaired but left open, so that today you can go from one room to the next along the path taken by the early explorers rather than through the doorways used by the Indians.

Section of wall at Aztec Ruins showing sealed door

at left.

From the plaza, the Indians gained access to these northwestern rooms by entering the west side rooms. Then, turning at right angles, they proceeded northward through the doorways and rooms until they reached the final row of rooms at the north.

Although not all are open to the public because of their difficulty of access, there are 19 rooms in the ruin which still have their original ceilings intact. In making a ceiling, the Indians used two or more main stringers—that is, large beams of pine or juniper—which they set into the walls of the room at a height of 8 or 9 feet, traversing the shorter dimension of the room. Running at right angles to the stringers, they placed cottonwood poles or splints of juniper, and, over these, reeds, rushes, or woven matting. Upon this they put adobe mud which was well packed to make a firm roof, or, if there was to be another room above it, a stout floor.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jan 13 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |