|

WHITMAN MISSION National Historic Site |

|

A Community Rises at Waiilatpu

The number of people at Waiilatpu in the winter of 1838—39 convinced Whitman that work on the new mission house had to be speeded up. Fortunately, he was able to hire Asahel Munger, who was a skilled carpenter. Munger had come out to Oregon as an independent missionary only to find that a person could not be independent in that vast, unsettled country. He eagerly accepted Whitman's offer.

The attractive, substantial mission house was built of the same materials as the first house. The new, T-shaped building had a wooden frame, walls of adobe bricks, and a roof of poles, straw, and earth. The walls were smoothed and whitewashed with a solution made from river mussel shells. Later, enough paint was acquired from the Hudson's Bay Company to paint the doors and window frames green, the interior woodwork gray, and the pine floors yellow. The main section of the house was a story-and-a-half high with three rooms on the ground floor and space for bedrooms above. From it extended a long, single-story wing which contained a kitchen, another bedroom, and a classroom. An out kitchen, storeroom, and other facilities were later added to the wing.

William Gray, who had moved back to Waiilatpu from Lapwai, built a third house in 1840-41. Situated 400 feet east of the mission house, it was a neat, rectangular adobe building. Gray and his wife lived in it only a short time. In 1842 he decided that his future lay else where than in the mission field. The Grays moved to western Oregon where they began an active life as settlers.

Although a blacksmith shop and a gristmill had been erected at Lapwai to serve all the stations, it became evident to Whitman that the central location of Waiilatpu required similar facilities there. In 1841 the blacksmith equipment was moved from Lapwai, and a small, adobe shop, 16 by 30 feet, was built half-way between the mission house and Gray's residence. Its adobe bricks were taken from the first house, which was torn down at this time. A corral was also built near this shop.

A small, improvised gristmill was built on the south side of the mission grounds in 1839. A second, more efficient mill soon replaced it. With this mill, Whitman was able to produce enough flour to supply the other stations and to sell to the emigrants of 1842. In addition, some of the Cayuse began to bring their grain to the mill. After Whitman had departed for the United States in the autumn of 1842, fire destroyed the mill. Not until 1844 did Whitman find the opportunity to build his third mill. Much larger than the others, the new gristmill had grinding stones 40 inches in diameter. Later, a threshing machine and a turning lathe were built on the mill platform. For waterpower to operate the mill, a ditch was dug from the Walla Walla River to a millpond formed by two long earthen dikes.

Although some pine timber had been handsawed in the Blue Mountains and dragged to the mission by horses, Whitman felt a dire need for a waterpowered sawmill. Among other things, he wanted to replace his leaky, earthen roofs with boards. He picked a spot on a stream in the foothills about 20 miles from the station and, by 1846, had the mill ready for operation. In 1847 a small cabin was built at the sawmill to house two emigrant families whom Whitman hired that autumn for a season of sawing. Physically, Waiilatpu was fast becoming the most substantial and comfortable of all the stations. From time to time, the other missionaries were just a shade envious of the Whitmans.

As the missionaries carried their work into the 1840's, they continued their efforts among the Indians. Whitman had his greatest success in teaching them the rudiments of agriculture. In 1843 he wrote that about 50 Indians had started farms, each cultivating from a quarter of an acre to three or four. The Cayuse also became interested in acquiring cattle, and by 1845 nearly all possessed the beginnings of a herd.

Much slower progress was made in education and religious instruction. To the Whitmans' disappointment, the Cayuse became less and less interested in learning the principles of Christianity. The demands made of them were too great for their simple and seminomadic way of life. Then, too, the Whitmans found they had less and less time to devote to Indian affairs. In addition to the multitude of details involved in the everyday job of acquiring food and shelter, the arrival of the annual emigrant trains from the United States demanded much time and energy from the Whitmans. Waiilatpu became not only an Indian mission but also an important station on the Oregon Trail.

At Lapwai, Spalding was having greater success among the Nez Percé and was able to convert several important Indian leaders. In 1839 he obtained a printing press from the American Board mission in Hawaii and printed parts of the Bible in the Nez Percé language. Both he and Asa Smith had difficulty in devising a workable alphabet. But on the second attempt, they contrived one that captured the sounds of the Nez Percé tongue. At Tshimakain and Kamiah the work of teaching and converting Indians proved a laborious and slow task. Although they recognized the difficulties facing them, the missionaries clung tenaciously to the idea of preparing the Indians for the day when white settlers would pour into the fertile lands of the Far West.

Meanwhile, the signs of white migration were becoming more plentiful at Waiilatpu, situated as it was on the main route of travel from the East. One of the ways in which this movement was making itself apparent was in the increasing number of white children who were to be seen at Whitman's station.

The Mission Press

In 1837 Henry Spalding became the first missionary to try writing a book in the Nez Percé language. But it was soon discovered that the alphabet devised by him was not adaptable to the Indians' tongue and this 72-page "primer" was never printed.

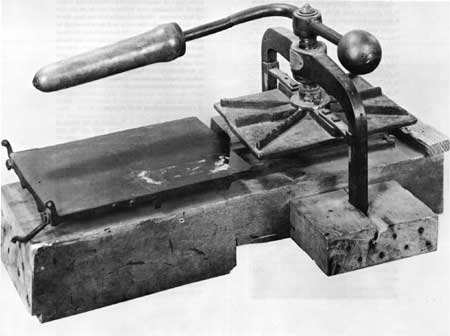

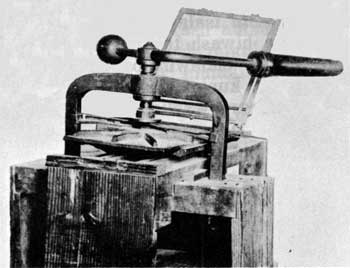

The next year, having received a new printing press themselves, the American Board missionaries in Hawaii (then called the Sandwich Islands) offered an older press to the Oregon missionaries. This, the first printing press in the Pacific Northwest, arrived at Lapwai in May 1839. With it came Edwin Hall who was to assist in starting the operation.

The press that printed the first books in the Pacific Northwest now reposes in the museum of the Oregon Historical Society, Portland.Eight days after setting up the press, the missionaries had proudly produced 400 copies of the first book printed in old Oregon. The authors, using an adaption of the alphabet employed in Hawaii, were Henry and Eliza Spalding and Cornelius Rogers. The significance of this achievement is not lessened by the fact that this book had only eight pages.

Between 1839 and 1845 a total of nine books were printed. The most elaborate of these was the Gospel according to St. Matthew turned out in Nez Percé by Spalding. All but one of the books were printed in the Nez Percé language; that one was a 16-page primer in Spokan translated by Elkanah Walker, the copies being stitched, pressed, and bound by his wife, Mary. All these imprints are now quite rare, and of one only a single copy is known to exist. This is the Nez Percé Laws, drawn up by Indian Agent Elijah White in 1842.

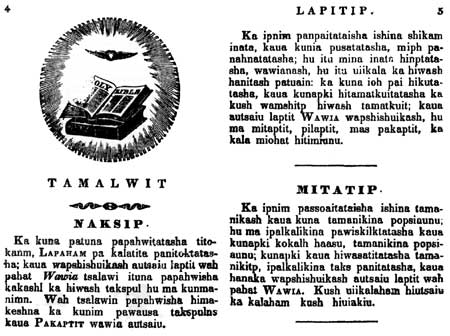

Page from Nez Percé Laws printed by Henry Spalding on the mission press.

WHITMAN COLLEGEReducing the Nez Percé language to writing was not an easy task. Asa Smith, the best linguist in the group, wrote: The] number of words in the language is immense & their variations are almost beyond description. Every word is limited & definite in its meaning & the great difficulty is to find terms sufficiently general. Again the power of compounding words is beyond description." But even as he struggled with this problem, Smith was convinced of the necessity of books: "We must have books in the native language, schools, & the Scriptures translated, or we are but beating the air. . . ."

By 1846 the missionaries had become pessimistic about their progress in publishing. The amount of effort required for just a few pages was tremendous. Their best linguists—Smith and Cornelius Rogers—were no longer with the mission. The Indians were not as receptive to the printed word as the missionaries had hoped. In that year the press was moved from Lapwai to The Dalles, and this first publishing venture came to a close. After the Whitman massacre, the press was used in the Willamette Valley by some men who were among the first newspaper publishers in the Pacific Northwest.

The immensity of this undertaking can be grasped only if one remembers the primitiveness of the land in 1839 when the missionaries distributed the first pages ever printed in the Oregon Country.

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |