|

GOLDEN SPIKE National Historic Site |

|

The race was in the final stretch,

The oceans soon would join.

No more months of heartbreak toil

To get coast to coast.

Black powder's blast, maul striking spike,

The music of an epic.

The final movement neared its end,

A symphony in iron.

A mile a day, then three, then eight,

The rails leaped 'cross the land,

As each road tried to best its foe,

To top its rival's deed.

From Eire and the Orient,

Came men to win the honor.

Ten miles of track in one day's work;

Just four more to the finish.

The Last Month

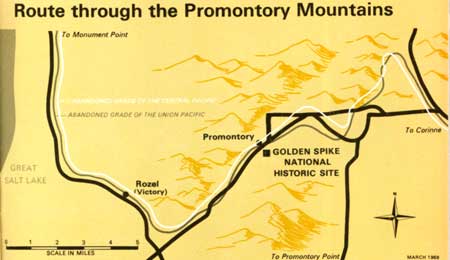

As the two railheads drew closer to each other, an air of excitement pervaded the construction camps north of Great Salt Lake, as well as the rest of the country, which followed the daily progress of the track-laying in the newspapers. The Central Pacific dismissed its contractors during the first week of April and pushed its Chinese crews forward to finish the grades on the Promontory. The Union Pacific rushed Irishmen to the front to help the Mormon contractors finish the heavy work on the east slope. By April 16 the U.P. and the C.P. tracks were only 50 miles apart. The Union Pacific, moving west across the sagebrush plain from Corinne, slowed for want of ties. The Central Pacific had reached Monument Point and, one-quarter of a mile from the lakeshore, established a sprawling grading camp. Housing the Chinese workers, it consisted of three separate canvas cities totaling 275 tents.

There were constant reminders of the approaching revolution in transcontinental travel. Trains of Russell, Majors, and Waddell freight wagons periodically passed the construction crews. Wells Fargo stagecoaches, which had once spanned the continent, now provided service between the railheads. The run of the coaches daily grew shorter as the rails moved forward 3 to 4 miles a day. For the Army, changes of station between East and West had once meant exhausting marches of several months duration across the western territories. In April 1869 the 12th Infantry, destined for the Presidio of San Francisco, detrained at Corinne and in 2 days marched to the Central Pacific railhead, where the soldiers boarded the train for the coast.

As April drew to a close, officials of the two companies fixed Saturday, May 8, as the date for the ceremony uniting the rails. By the 27th the Union Pacific railhead approached Blue Creek, 10 miles east of the Summit. But rock cuts and three trestles required another 12 to 15 days of labor, even though Reed, in order to break through by May 8, worked his Mormons and Irishmen night and day. While blasters tore at Carmichael's Cut, 1/4 miles above the unfinished Big Trestle, workmen built another trestle at the cut's west entrance. A third trestle spanned Blue Creek. Stanford went to the Union Pacific railhead and offered to let the U.P. run its track across the C.P.'s Big Fill, but found no one with authority to change the line.

Earlier, the Union Pacific had laid 8 miles of track in 1 day—a feat, they boasted, that the Central Pacific had not accomplished. Crocker vowed to top this record, but he cannily waited until the distance between railheads was so short that the U.P. could not retaliate. On April 27, with the Central Pacific 16 miles from the Summit and the Union Pacific, 9, Crocker set out to lay 10 miles of rail in 1 day. But a work train jumped the track after 2 miles had been completed, and he decided to wait until the next day.

At 7:15 a.m., on April 28, with men and supplies carefully massed for the attempt, and with Casement, Reed, and other U.P. officials as witnesses, Crocker gave the signal to start. At once, eight Irish track-layers supported by an army of Chinese coolies set to work to top the Union Pacific record. The correspondent of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin vividly described the activity:

Each of the four front men ran thirty feet with one hundred and twenty-five tons. Each of the other four men lifted and placed one hundred and twenty tons at their end of the rails. The distance travelled was over ten miles, besides extra walking . . . . Those eight men would not consent to shift, and are proud of their work. They, like all Central Pacific men, are water-drinkers.

Immediately in front of the eight are three pioneers, who, with shovel and by hand, set the ties thrown by the front teams in position; while this is doing, another party are distributing spikes and fresh bolts at each end of the rail, while some of the party are regulating the gauge. These track-layers are a splendid force, and have been settled and drilled until they move like machinery. . . .

Beside the track-layers come the spike-starters, who place all the spikes needed in position; then comes a reverend-looking old gentleman who packs the rails and uses the line, and, by motion of his hands, directs the track-straighteners. The next men to the spike-drivers are the bolt screwers, quite a large force. Behind them come the tampers, four hundred strong, with shovels and crow-bars. They level the track by raising or lowering the ends of the ties, and shovel in enough ballast to hold them firm. When they leave it, the line is fit for trains running twenty-five miles an hour. When all the iron thrown on the track has been laid, the handcars run to the extreme front, and the locomotive and iron train come as close to the front as possible; another two miles of iron is thrown off, and the process repeated. Alongside of the moving force are teams hauling tools, and water-wagons, and Chinamen, with pails strung over their shoulders, moving among the men with water and tea. . . .

The scene is a most animated one. From the first pioneer to the last tamper, perhaps two miles, there is a thin line of 1,000 men advancing a mile an hour; the iron cars, with their living and iron freight, running up and down; mounted men galloping backward and forward. Far in the rear are trains of material, with four or five locomotives, and their water-tanks and cars . . . . Keeping pace with the track-layers was the telegraph construction party, hauling out, and hanging, and insulating the wire, and when the train of offices and houses stood still, connection was made with the operator's office, and the business of the road transacted . . . .

By 1:30 p.m. the track had advanced 6 miles in 6 hours and 15 minutes. The remaining 4 miles could easily be laid. The C.P. crews knew that victory had been won, and Crocker stopped the work for lunch. The site, named Camp Victory, later became the station of Rozel. After an hour of rest the workers returned to the task. By 7 p.m. they had completed more than 10 miles of track, thus topping the U.P., and a locomotive ran the entire distance in 40 minutes to prove to U.P. observers that the work was well done.

Jack Casement Stanford University |

April 28 carried the Central Pacific railhead to within 4 miles of the Summit. With the Union Pacific still at Blue Creek, Eicholtz ordered iron and ties hauled to the Summit. On May 1 U.P. crews began putting in a sidetrack at the Summit, where tents already announced the birth of the town of Promontory. This same day the C.P. brought its rails to the Summit, 690 miles from Sacramento, the end of the line.

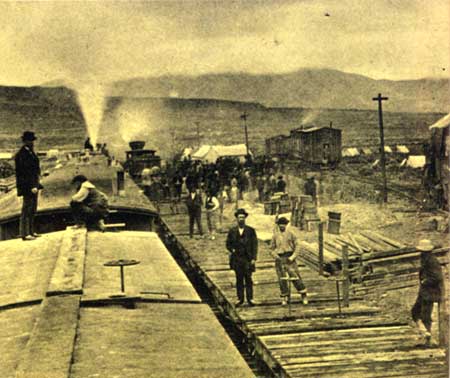

During the first few days of May the population at the Promontory reached its maximum. C.P. camps stretched all the way from Promontory to Monument Point, while U.P. camps dotted the valley of the Summit and cluttered the plain at the foot of the east slope. They bore such names as Deadfall, Murder Gulch, Last Chance, and Painted Post. Jack Casement's headquarters train stood on a siding one-half mile east of Blue Creek bridge. A 68,000-gallon tank, fed by pipes leading to a spring in the hills, had been built at this siding to furnish the camps with water.

The Union Pacific camps here rocked with the riotous living that had characterized their predecessors all the way from Omaha. Noted a reporter from San Francisco:

The loose population that has followed up the track-layers of the Union Pacific is turbulent and rascally. Several shooting scrapes have occurred among them lately. Last night [April 27] a whiskey-seller and a gambler had a fracas, in which the "sport" shot the whiskey dealer, and the friends of the latter shot the gambler. Nobody knows what will become of these riff-raff when the tracks meet, but they are lively enough now and carry off their share of the plunder from the working men.

Nor was all peace and quiet in the Central Pacific camps, although the California papers delighted in emphasizing the low moral tone of the Union Pacific. At Camp Victory on May 6, the Chinese clans of See Yup and Yung Wo, whose rivalry stemmed from political differences in the old country, got into an altercation over $15 due one group from the other. The dispute grew heated and soon involved several hundred laborers. "At a given signal," reported a correspondent, "both parties sailed in, armed with every conceivable weapon. Spades were handled, and crowbars, spikes, picks, and infernal machines were hurled between the ranks of the contestants." When shooting broke out, Strobridge and his foreman intervened to halt the fracas. The score, aside from a multiplicity of cuts, bruises, and sore heads, totaled one Yung Wo combatant mortally wounded.

Irish graders of the Union Pacific, on the other side of the Promontory, heard about the battle between the Chinese clans. They decided to have some fun themselves. Next day a gang of them showed up at Promontory, where a Chinese camp had been laid out, and announced their intention "to clean out the Chinese." Fortunately, the inhabitants of this camp were absent on a gravel train, and the Irishmen left without accomplishing their purpose.

Both companies had already recognized that they had more men on the Promontory than the amount of remaining work could keep occupied. Beginning on May 3, therefore, they began discharging large numbers of men and sending others to the rear to work on parts of track that had been hastily laid. "The two opposing armies . . . are melting away," reported the Alta California, "and the white camps which dotted every brown hillside and every shady glen . . . are being broken up and abandoned." Riding out from Salt Lake City, photographer Charles R. Savage saw this breakup in progress and wrote in his diary: "At Blue River [Creek] the returning 'democrats' so-called were being piled upon the ears in every stage of drunkenness. Every ranch or tent has whiskey for sale. Verily, men earn their money like horses and spend it like asses."

Camp Victory

Stanford University

On May 5 the Union Pacific finally achieved the breakthrough. The last spike went into the Big Trestle and the rails moved out onto the frightening span. A train loaded with iron steamed across it. That evening the final blast exploded in Carmichael's Cut. On May 6 the trestle between Carmichael's Cut and Clark's Cut was finished. The graders went through both cuts, made a swing around the head of a ravine, and passed though a final cut to link up the grade already laid in the basin of the Summit. Here rails and ties had been arranged for rapid track-laying and, at the Summit itself, a 2,500-foot sidetrack installed.

The Central Pacific waited patiently—May 8 was still the date for joining the rails—as the Union Pacific track-layers followed closely on the heels of the graders. Late in the afternoon of May 7 the track-layers came within 2,500 feet of the C.P.'s end-of-track at the Summit. Here they connected, by a switch, with the sidetrack built earlier. Using this sidetrack, the Union Pacific's No. 60, with Casement aboard, came to a halt opposite the Central Pacific railhead, about 100 feet to the southeast of it, and let off steam. The Central's "Whirlwind" rested on its own track. The engineer greeted the Union's locomotive with a sharp whistle. "The first meeting of locomotives from Atlantic and Pacific took place."

Only 2,500 feet remained. The next day, May 8, the final drama was supposed to be enacted, but the Union Pacific could not meet the schedule. The last spike was not driven until May 10.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |