|

GOLDEN SPIKE National Historic Site |

|

They joined the rails from East and West.

They drove the Golden Spike.

They marked the day with wine and cheers,

And then they signalled "Done."

A railroad built in record time.

The builders justly proud.

They bound the land with bands of iron,

Began the frontier's end.

Driving the Last Spike

At Promontory the afternoon of May 7 was sultry and the sky heavy with rain clouds, which annoyed the photographers trying to capture the climactic scenes of construction. The Stanford Special arrived with an array of dignitaries from California and Nevada headed by Leland Stanford.

Also aboard were the ceremonial trappings to be used in uniting the rails. There was a golden spike presented by David Hewes, San Francisco construction magnate. Intrinsically worth $350, it was engraved with the names of the C.P. Directors, sentiments appropriate to the occasion, and, on the head, the notation "The Last Spike." There was another gold spike, presented by the San Francisco News Letter; a silver spike brought by U.S. Commissioner J. W. Haines as Nevada's contribution; and a spike of iron, silver, and gold brought by Gov. A. P. K. Safford to represent Arizona. (Arizonians knew nothing of it. Safford had not yet taken office and had never been in Arizona.) Finally, there was a sliver-plated sledge presented by the Pacific Union Express Company, and a polished laurel tie presented by West Evans, the Central Pacific's tie contractor.

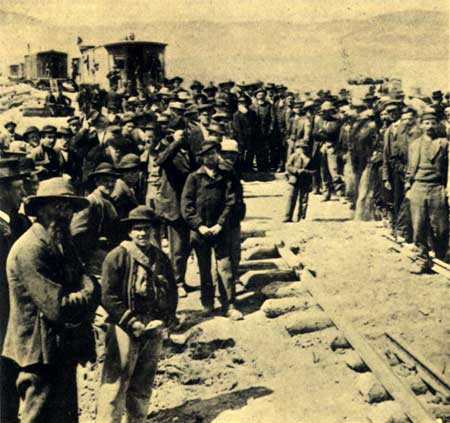

Waiting for the last rails to be laid at Promontory,

May 10, 1869.

Union Pacific

The festive mood of the Stanford Special noticeably dampened when Jack Casement broke the news that the Union Pacific could not hold the ceremony on May 8, as planned, and would not be ready until May 10. The Stanford party faced the prospect of spending the weekend on the bleak Promontory. To make matters worse, rain began falling. It continued for 2 days, turning Promontory Summit into a sea of mud. Stanford wired the unwelcome news to San Francisco, but too late. The citizens there had already started celebrating. Undismayed, they celebrated for 3 days.

Casement's explanation for the delay was that the trains bringing the dignitaries from the East had been held up in Weber Canyon. Heavy rains had made the roadbed soft and had washed out a trestle. But there was another reason, too. The special train carrying Vice President Durant, Sidney Dillon, and other U.P. officials had reached Piedmont, Wyo., on May 6. A gang of 500 workers surrounded Durant's private car shouting demands for back wages. When the conductor tried to move the train out of the station, the men uncoupled Durant's car, shunted it onto a siding, and chained the wheels to the rails. Here he would stay, they said, until their pay was forthcoming. To make sure, they also took possession of the telegraph office. Durant submitted, wired Oliver Ames in Boston for the money, and paid off the strikers. He was released and managed to be at Promontory on May 10, although the severe headache he suffered that day may well have owed its origin to the experience at Piedmont.

Left in the role of host at Promontory, Casement made up an excursion train, stocked with "a bountiful collation and oceans of champagne," to take the Stanford party sightseeing. The train left Promontory Saturday morning. At Taylor's Mill the Union Pacific staged a "splendid luncheon" on the banks of the Weber River. "The most cordial harmony and good feeling marked their entertainment and all the toasts were drank with loud applause," reported a correspondent. From here the party went to Ogden, rode a short distance up Weber Canyon, and spent the night in Ogden. Next day, Sunday, they returned to Promontory, boarded the Stanford Special, and pulled back to Monument Point to enjoy a repast of plover.

This same day, May 9, Casement's workers at Promontory kept busy. As the rain continued, they laid the final 2,500 feet of track, leaving a length of one rail separating their track from that of the Central Pacific. They also installed a Y for the locomotives to use in turning around.

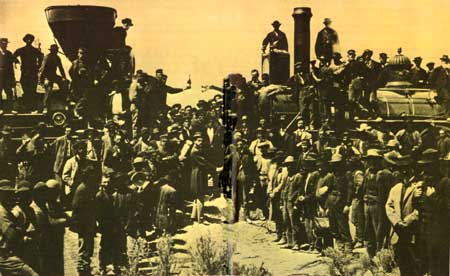

The joining of the rails at Promontory, May 10, 1869. Shaking

hands in center are chief engineers Samuel S. Montague of C.P., and Grenville

M. Dodge of U.P.

The rain ended during the night and May 10 dawned bright, clear, and a bit chilly. During the morning two trains from the East and two from the West arrived at Promontory bearing railroad officials, guests, and spectators. With the construction workers and assorted denizens of Promontory, the crowd totaled, according to the best estimates, 500 to 600 people—far short of the 30,000 that had been predicted.

Among those representing the Central Pacific were Stanford, Strobridge, Montague, and Gray; for the Union Pacific, Durant, Dillon, Duff, Dodge, Reed, and the Casement brothers. Important guests had come from Nevada, California, Utah and Wyoming. Huntington, Hopkins, and Crocker, of the C.P. did not attend; nor did the U.P.'s Oakes and Oliver Ames. Brigham Young sent Bishop John Sharp to represent the Mormon Church. About 15 reporters covered the proceedings. A battalion of the 21st Infantry under Maj. Milton Cogswell, enroute to the Presidio of San Francisco, was opportunely on hand to lend a military air. The military band from Fort Douglas and the 10th Ward Band from Salt Lake City supplied the music.

Officials of both roads had been unable to agree on details of the program. Stanford had come equipped with spikes and other ceremonial trappings, but Dodge wanted the Union Pacific to stage its own last spike ceremony. Only two preparations had been made in advance. The speeches had been written and handed to newsmen in Ogden on Sunday, and the telegraphers had devised an apparatus for transmitting the blows on the last spike by telegraph to the waiting Nation. An ordinary sledge (not the silver-plated one) had been connected by wire to the Union Pacific telegraph line, and an ordinary spike had been similarly connected to the Central Pacific wire. Five minutes before noon, when the proceedings were to begin, Stanford and Durant agreed on a joint program.

The crowd had grown loud and unmanageable, which interfered with the ceremony and made it impossible for most people to see what was happening. One reporter wrote that "it is to be regretted that no arrangements were made for surrounding the work with a line of some sort, in which case all might have witnessed the work without difficulty. As it was, the crowd pushed upon the workmen so closely that less than twenty persons saw the affair entirely, while none of the reporters were able to hear all that was said." This explains the confusion that has surrounded the history of the event.

At noon the infantrymen lined up on the west side of the tracks, and Casement tried, with little success, to get the crowd to move back so that everyone could see. The Union Pacific's No. 119, with Engineer Sam Bradford, and the Central Pacific's "Jupiter," with Engineer George Booth, steamed up and stopped, facing each other across the gap in the rails. Spectators swarmed over both locomotives trying to obtain a better view. At 12:20 p.m. Strobridge and Reed carried the polished laurel tie and placed it in position. Auger holes had been carefully bored in the proper places for seating the ceremonial spikes. Officials and prominent guests formed a semicircle on the east side of the tracks.

Edgar Mills, a Sacramento businessman, served as master of ceremonies and introduced the Rev. Dr. John Todd of Pittsfield, Mass., correspondent for the Boston Congregationalist and the New York Evangelist. Dr. Todd opened the ceremony with a 2-minute prayer, while telegraph operators from Atlantic to Pacific cleared the wires for the momentous clicks from Promontory. At 12:40 p.m., W. N. Shilling, a telegraph key on a small table in front of him, tapped out: "We have got done praying. The spike is about to be presented."

Next, Dr. W. H. Harkness of Sacramento presented to Durant, with appropriate remarks, the two gold spikes. Durant slid them into the holes in the laurel tie, and Dodge made the response. U.S. Commissioner F. A. Tritle and Governor Safford presented the Nevada and Arizona spikes, and these Stanford slid into the holes prepared. L. W. Coe, President of Pacific Union Express Company, presented Stanford with the silver sledge, which was then used symbolically to "drive" the precious spikes, although the blows, if indeed any were given, were not sharp enough to leave marks on the spikes.

Finally came the actual driving of the last spike—an ordinary iron spike driven with an ordinary sledge into an ordinary tie. Using the wired sledge, Stanford and Durant both swung at the wired spike. Both missed, to the delight of the crowd. Shilling, however, clicked three dots over the wires at exactly 12:47 p.m., triggering celebrations at every major city in the country. With an unwired sledge, Strobridge and Reed divided the task of actually driving the last spike in the Pacific Railroad,

Amid cheers, the two engineers advanced the pilots of their locomotives over the junction. Men on the pilots joined hands, and a bottle of champagne was broken over the laurel tie as christening. The chief engineers of the railroad shook hands as the photographers exposed wet plates. The military officers and their wives gave the precious spikes ceremonial taps with the tangs of their sword hilts. The Central Pacific's "Jupiter" backed up and the Union Pacific's No. 119 crossed the junction. Then No. 119 backed up and let "Jupiter" cross the junction, thus symbolizing the inauguration of transcontinental rail travel.

Central Pacific's "Jupiter" and Union Pacific's No. 119

Southern Pacific and Union Pacific photos

Shilling sent off two telegrams: "General U. S. Grant, President of the U.S., Washington, D.C. Sir: We have the honor to report the last rail laid and the last spike driven. The Pacific Railroad is finished." "To the Associated Press: The last rail is laid, the last spike driven, the Pacific railroad is completed. Point of Junction, ten hundred eighty-six miles west of the Missouri river and six hundred ninety miles east of Sacramento—Leland Stanford, Thomas C. Durant."

The ceremony over, the precious spikes and tie were removed. Even so, souvenir hunters made necessary numerous replacements of the "last spike" and the "last tie." Central Pacific's "Jupiter" soon left for Sacramento, but Union Pacific's No. 119 remained until evening, presenting, as one reporter observed, "a scene of merriment in which Officers, Directors, Track Superintendents and Editors joined with the utmost enthusiasm." It was late when the celebration ended.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |