|

GOLDEN SPIKE National Historic Site |

|

They drove the Spike and then they left.

The armies marched away.

A town grew up, a sickly thing,

Of gamblers, bars, and "droves."

For half a year the changing point,

And then it slowly died.

Promontory After May 10, 1869

Promontory had enjoyed its hour of glory, but the town did not immediately die. The two companies did not agree on a price for the Promontory-Ogden section until November 1869. For nearly a year Promontory served as the terminus, where passengers transferred from one railroad to the other. Union Pacific trains turned around on the Y that had been installed on May 9, while Central Pacific trains used a turntable built shortly before the rails were joined on May 10.

During the months that it served as the terminus, Promontory resembled the other boomtowns that had followed the Union Pacific across the country. A string of boxcars on a siding provided offices and living quarters for railroad employees. A row of tents, many with false board fronts, faced the railroad across a single dirt street. They housed hotels, lunch counters, saloons, gambling dens, a few stores and shops, and the nests of the "soiled doves." Signs advertised such alcoholic potations as "Red Cloud," "Red Jacket," and "Blue Run." Liquor sales boomed. Water was scarce. The nearest source was 6 miles away, and the railroads were forced to haul long strings of tank cars full of water to Promontory from springs 30 to 50 miles distant.

A large number of "hard cases" descended on Promontory, including, reported the correspondent of the Sacramento Bee, "Behind-the-Rock Johnny, hero of at least five murders and unnumbered robberies." Three-card monte, ten-die, strap game, chuck-a-luck, faro, and keno flourished in the gambling tents. A gang of cutthroat gamblers and confidence men called the "Promontory Boys" set up headquarters and were "thicker than hypocrites at a camp meeting of frogs after a shower." Their modus operandi was to put "cappers" aboard the trains at Kelton or Corinne to gain the confidence of passengers. At Promontory the cappers led their victims to one of the gambling tents and into the clutches of the Promontory Boys.

Promontory's life as a "hell on wheels" boomtown was a short but lively one. J. H. Beadle, editor of the Utah Daily Reporter, summed up its character when he wrote: "4,900 feet above sea level, though theologically speaking, if we interpret scripture literally, it ought to have been 49,000 feet below that level; for it certainly was, for its size, morally nearest to the infernal regions of any town on the road."

The trestles on the Union Pacific line ascending the east slope of the Promontory continued to be a source of concern. A Government inspector, Isaac N. Morris, in May 1869 reported to President Grant on this part of the line, grudgingly approving all except the trestles.

For a mile and a half [going east from Promontory] the ties . . . are virtually laid on the ground, but the road then passes through several sand-banks, some comparatively small and some of formidable proportions, with intervening spaces of nearly level surface; thence it passes through rock excavations, one being some forty feet deep and a quarter of a mile long through the heaviest body of the mountain, overlooking Salt Lake; thence it sweeps around the mountain's side to its base, describing in its course a succession of short curves, so sharp indeed that an ascending and descending train would collide before either would be aware of the proximity of the other. I measured the width of the cuts, and found them so nearly in compliance with the standard of construction that they may be so regarded. Before reaching the descending curve running on the side of the mountain, two dells or ravines are crossed on trestle-work, one as nearly as I could judge . . . about two hundred and fifty feet long and thirty feet deep. These trestle-structures, unknown to the law, but familiar to the line of the road, and one over Blue Creek, not far distant, are very frail and dangerous. It is the purpose of the company, I was told, to fill up these ravines so as to have a solid road bed over them. The sooner this is done the better for the safety of lives and property. . . .

Promontory in late summer, 1869.

Union Pacific

After the Central Pacific took over the line from Promontory to the terminus near Ogden, it eliminated the two trestles on the slope. The company did this apparently sometime during 1870 by laying track on its own grade, installed during the great railroad race. Thus the new line followed the C.P. grade from somewhere near the eastern base of the Promontory, across the Big Fill parallel to the Big Trestle, across another fill parallel to the trestle connecting Carmichael's and Clark's Cuts, and thence in a sweep to the north across the valley to the Summit.

With transfer of the terminus to Ogden in early 1870, the lusty days of Promontory came to an end. The Central Pacific, however, built a station, water tank, and roundhouse at Promontory. Locomotives pulling heavy trains required additional power to climb the east slope, and the company kept helper-engines at the summit for this purpose. The town also became headquarters of a railroad cattle enterprise, and the company built the "Crocker Mansion" about 1 mile to the northwest. With eight bedrooms and as many bathrooms, it was a showplace of northern Utah. It later deteriorated and was moved to the nearby community of Howell.

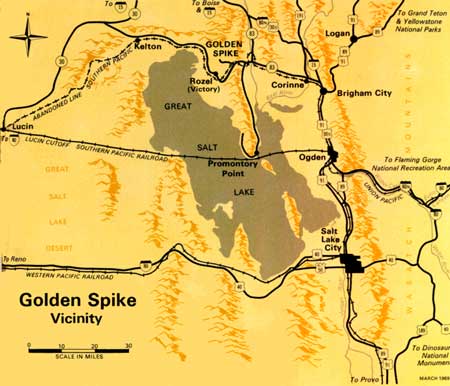

In 1902 the Southern Pacific Railroad, which had absorbed the Central Pacific, decided to shorten the line by building a trestle across Great Salt Lake. When finished in 1904, the Lucin Cutoff replaced the original line running north of the lake, although the Promontory line continued to be used occasionally when bad weather threatened the cutoff. Finally, in 1942, the company tore up the rails between Lucin and Corinne and contributed the scrap iron to the war effort. Amid ceremonies with two engines facing each other, workmen began the task by pulling up the "last spike" at Promontory.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |