|

MORRISTOWN National Historic Park |

|

The First Winter Encampment in Morris

County

SITUATION: JANUARY 1777. Sir William Howe had been mistaken. Near the middle of December 1776, as Commander in Chief of His Majesty's army in America, he believed the rebellion of Great Britain's trans-Atlantic colonies crushed beyond hope of revival. "Mr." Washington's troops had been driven from New York, pursued through New Jersey, and forced at last to cross the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. The British had captured Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, the only American general they thought possessed real ability. Some mopping up might be necessary in the spring, but the arduous work of conquest was over. Howe could spend a comfortable winter in New York, and Lord Cornwallis, the British second in command, might sail for England and home.

Then suddenly, with whirlwind effect, these pleasant reveries were swept away in the roar of American gunfire at Trenton in the cold, gray dawn of December 26, and at Princeton on January 3. Out generaled, bewildered, and half in panic, the British forces pulled back to New Brunswick. Now they were 60 miles from their objective at Philadelphia, instead of 19. Worst of all, they had been maneuvered into this ignominious retreat by a "Tatterde-mallion" army one-sixth the size of their own, and they were on the defensive. "We have been boxed about in Jersey," lamented one of Howe's officers, "as if we had no feelings." George Washington with his valiant comrades in arms had weathered the dark crisis. For the time being at least, the Revolution was saved.

The Ford Powder Mill, built by Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., in 1776. |

The Old Morris County Courthouse of Revolutionary War times. |

FROM PRINCETON TO MORRISTOWN. Washington's original plan at the beginning of this lightninglike campaign was to capture New Brunswick, where he might have destroyed all the British stores and magazines, "taken (as we have since learnt) their Military Chest containing 70,000 £ and put an end to the War." But Cornwallis, in Trenton, had heard the cannon sounding at Princeton that morning of January 3, and, just as the Americans were leaving the town, the van of the British Army came in sight. By that time the patriot forces were nearly exhausted, many of the men having been without any rest for 2 nights and a day. The 600 or 800 fresh troops required for a successful assault on New Brunswick were not at hand. Washington held a hurried conference with his officers, who advised against attempting too much. Then, destroying the bridge over the Millstone River immediately east of Kingston, the Continentals turned north and marched to Somerset Court House (now Millstone), where they arrived between dusk and 11 o'clock that night.

Washington marched his men to Pluckemin the next day, rested them over Sunday, January 5, and on the Monday following continued on northward into Morristown. There the troops arrived, noted an American officer, "at 5 P. M. and encamped in the woods, the snow covering the ground." Thus began the first main encampment of the Continental Army in Morris County.

The Ford Mansion, shelter for Delaware troops in 1777 and occupied

as Washington's headquarters during the terrible winter of

1779—80.

THE NEW BASE OF AMERICAN OPERATIONS. A letter dated May 12, 1777, described the Morristown of that day as "a very Clever little village, situated in a most beautiful vally at the foot of 5 mountains." Farming was the mainstay of its people, some 250 in number and largely of New England stock, but nearby ironworks were already enriching a few families and employing more and more laborers. Among the 50 or 60 buildings in Morristown, the most important seem to have been the Arnold Tavern, the Presbyterian and Baptist Churches, and the Morris County Courthouse and Jail, all located on an open "Green" from which streets radiated in several directions. There were also a few sawmills, gristmills, and a powder mill, the last built on the Whippany River, in 1776, by Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., commander of the Eastern Battalion, Morris County Militia. Colonel Ford's dwelling house, then only a few years old, was undoubtedly the handsomest in the village.

Washington's immediate reasons for bringing his troops to Morristown were that it appeared to be the place "best calculated of any in this Quarter, to accomodate and refresh them," and that he knew not how to obtain covering for the men elsewhere. He must have been impressed also with the demonstrated loyalty of Morris County to the patriot cause, even in those dreary, anxious weeks of late 1776 when its militia helped considerably to stave off attempted enemy incursions directly westward from the vicinity of New York. Finally, there were already at Morristown three Continental regiments previously ordered down from Fort Ticonderoga, and union with these would strengthen the forces under his personal command.

The Arnold Tavern, where Washington reputedly stayed in

1777.

Even so, Washington hoped at first to move again before long, and it was only as circumstances forced him to remain in this small New Jersey community that its advantages as a base for American military operations became fully apparent. From here he could virtually control an extensive agricultural country, cutting off its produce from the British and using it instead to sustain the Continental Army. In the mountainous region northwest of Morristown were many forges and furnaces, such as those at Hibernia, Mount Hope, Ringwood, and Charlottenburg, from which needed iron supplies might be obtained. The position was also difficult for an enemy to attack. Directly eastward, on either side of the main road approach from Bottle Hill (now Madison) large swamp areas guarded the town. Still further east, almost midway between Morristown and the Jersey shore, lay the protecting barriers of Long Hill, and the First and Second Watchung Mountains. Their parallel ridges stretched out for more than 30 miles, like a huge earthwork, from the Raritan River on the south toward the northern boundary of the State, whence they were continued by the Ramapos to the Hudson Highlands. In addition to all this, the village was nearly equidistant from Newark, Perth Amboy, and New Brunswick, the main British posts in New Jersey, so that any enemy movement could be met by an American counterblow, either from Washington's own outposts or from the center of his defensive-offensive web at Morristown itself. A position better suited to all the Commander in Chiefs purposes, either in that winter of 1777 or in the later 1779—80 encampment period, would have been hard to find.

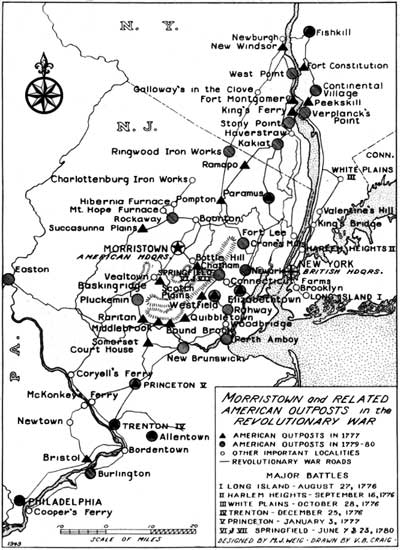

Morristown and Related American Outposts in the

Revolutionary War.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

WINTER QUARTERS FOR OFFICERS AND MEN. Local tradition has it that upon arriving in Morristown, on January 6, Washington went to the Arnold Tavern, and that his headquarters remained there all through the 1777 encampment period. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene lodged for a time "at Mr. Hoffman's,—a very good-natured, doubtful gentleman." Captain Rodney and his men were quartered at Colonel Ford's "elegant" house until about mid-January, when they left for Delaware and home.

Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne, on rejoining Washington in the spring of 1777, is said to have stayed at the homestead of Deacon Ephraim Sayre, in Bottle Hill. It has been stated that other officers, and a large number of private soldiers as well, were given shelter in Morristown or nearby villages by the Ely, Smith, Beach, Tuttle, Richards, Kitchell, and Thompson families.

Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene. |

Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne. |

According to the Reverend Samuel L. Tuttle, a local historian writing in 1871, there was also a campground for the troops about 3 miles south east of Morristown on what were then the farms of John Easton and Isaac Pierson, in the valley of Loantaka Brook. Tuttle obtained his information from one Silas Brookfield and other eyewitnesses of the Revolutionary scene, who claimed that the troops built a village of log huts at that location. It is highly curious that not one of Washington's published letters or orders refers to such buildings, nor are they mentioned in any other contemporary written records studied to date.

INSTABILITY OF THE ARMY. However the troops were sheltered, it was not long before the army which had fought at Trenton and Princeton began to melt away. Deplorable health conditions, lack of proper clothing, insufficient pay to meet rising living costs, and many other instances of neglect had discouraged the soldiery all through the 1776 campaign. The volunteer militiamen were particularly dissatisfied. Some troops were just plain homesick, and nearly all had already served beyond their original or emergency terms of enlistment. They had little desire for another round of hard military life.

Washington described his situation along this line in a letter of January 19 addressed to the President of Congress: "The fluctuating state of an Army, composed Chiefly of Militia, bids fair to reduce us to the Situation in which we were some little time ago, that is, of scarce having any Army at all, except Reinforcements speedily arrive. One of the Battalions from the City of Philadelphia goes home to day, and the other two only remain a few days longer upon Courtesy. The time, for which a County Brigade under Genl. Muffin came out, is expired, and they stay from day to day, by dint of Solicitation. Their Numbers much reduced by desertions. We have about Eight hundred of the Eastern Continental Troops remaining, of twelve or fourteen hundred who at first agreed to stay, part engaged to the last of this Month and part to the middle of next. The five Virginia Regts. are reduced to a handful of Men, as is Col Hand's, Smallwood's, and the German Battalion. A few days ago, Genl Warner arrived, with about seven hundred Massachusetts Militia engaged to the 15th [of] March. Thus, you have a Sketch of our present Army, with which we are obliged to keep up Appearances, before an Enemy already double to us in Numbers."

FOOD AND CLOTHING SHORTAGES. Meanwhile, as the Commander in Chief noted in another letter of nearly the same date, his few remaining troops were "absolutely perishing" for want of clothing, "Marching over Frost and Snow, many without a Shoe, Stocking or Blanket." Nor, due to certain inefficiencies in the supply services, was the food situation any better. "The Cry of want of Provisions come to me from every Quarter," Washington stormed angrily on February 22 to Matthew Irwin, a Deputy Commissary of Issues: "Gen. Maxwell writes word that his People are starving; Gen. Johnston, of Maryland, yesterday inform'd me, that his People could draw none; this difficulty I understand prevails also at Chatham! What Sir is the meaning of this? and why were you so desirous of excluding others from this business when you are unable to accomplish it yourself? Consider, I beseech you, the consequences of this neglect, and exert yourself to remove the Evil." Even in May, near the end of the 1777 encampment, there was an acute shortage of food.

RECRUITMENT GETS UNDER WAY. In this situation, Washington wrought mightily to "new model" the American fighting forces. Late in 1776, heeding at last his pressing argument for longer enlistments, Congress had called upon the States to raise 88 Continental battalions, and had also authorized recruitment of 16 "additional battalions" of infantry, 3,000 light horse, three regiments of artillery, and a corps of engineers. A magnificent dream of an army 75,000 strong! Washington knew, however, that it was more than "to say Presto begone, and every thing is done." Very early that winter he sent many of his general officers into their own States to hurry on the new levies. Night and day, too, he was in correspondence with anyone who might help in the cause, writing prodigiously. Still the business lagged painfully. "I have repeatedly wrote to all the recruiting Officers, to forward on their Men, as fast as they could arm and cloath them," the Commander in Chief advised Congress on January 26, "but they are so extremely averse to turning out of comfortable Quarters, that I cannot get a Man to come near me, tho' I hear from all parts, that the recruiting Service goes on with great Success." For nearly 3 months more, as events turned out, he had to depend for support on ephemeral militia units, "here to-day, gone to-morrow." April 5 found him still wondering if he would ever get the new army assembled.

Sketches of the Baptist Church(left) and the

Presbyterian Church (right) at Morristown, both used as

smallpox hospitals in 1777.

SICKNESS AND DEATH. But the patriot cup of woe was not yet filled, and there was still another evil to fight. This was smallpox, which together with dysentery, rheumatism, and assorted "fevers" had victimized hundreds of American troops in 1776. Now the dread disease threatened to run like wildfire through the whole army, old and new recruits alike.

Medical knowledge of that day offered but one real hope of saving the Continental forces from this "greatest of all calamities," namely, to communicate a mild form of smallpox by inoculation to every soldier who had not yet been touched by the contagion, thus immunizing him against its more virulent effects "when taken in the natural way." Washington was convinced of this by the time he arrived at Morristown on January 6. He therefore ordered Dr. Nathaniel Bond to prepare at once for handling the business of mass inoculation in northern New Jersey, and instructed Dr. William Shippen, Jr., to inoculate without delay both the American troops then in Philadelphia and the recruits "that shall come in, as fast as they arrive." During the next 3 months, similar instructions or suggestions were sent to officers and civil authorities connected with recruitment in New York, New Jersey, New England, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

Undertaken secretly at first, the bold project was soon going full swing throughout Morristown and surrounding villages. Inoculation centers were set up in private houses, with guards placed over them to prevent "natural" spread of the infection. The troops went through the treatment in several "divisions," at intervals of 5 or 6 days. Washington waxed enthusiastic as the experiment progressed. "Innoculation at Philadelphia and in this Neighbourhood has been attended with amazing Success," he wrote to the Governor of Connecticut, "and I have not the least doubt but your Troops will meet the same." As of March 14, however, about 1,000 soldiers and their attendants were still incapacitated in Morristown and vicinity, leaving but 2,000 others as the army's total effective strength in New Jersey. A blow struck by Sir William Howe at that time might have been disastrous for the Americans. Fortunately, it never came.

The episode was not without its tragic side, however. Since smallpox in any form was highly contagious, civilians in the whole countryside near the camp also had to be inoculated along with the army. Some local people, and a small number of soldiers as well, contracted the disease naturally before the project got under way, or perhaps refused submission to the treatment. Isolation hospitals for these unfortunates were established in the Presbyterian and Baptist Churches at Morristown, and in the Presbyterian Church at Hanover. The patients died like flies. In the congregation of the Morristown Presbyterian Church alone, no less than 68 deaths from smallpox were recorded in 1777. Those who survived the ordeal were almost always pockmarked by it.

WASHINGTON TIGHTENS HIS GRIP ON NEW JERSEY. Running the gauntlet of these and other problems, all at the same time, was discouraging for Washington, to say the least. Few generals have ever been more skilled, however, in ferreting out their opportunities, or in making better use of them. Nearly on a par with his remarkable victories at Trenton and Princeton was the way in which he reasserted patriot control over most of New Jersey during the winter and spring of 1777, excepting only the immediate neighborhood of New Brunswick and Perth Amboy. Even there, as time went on, the American pressure became more or less constant.

Stationing bodies of several hundred light troops at Princeton, Bound Brook, Elizabethtown, and other outlying posts, the Commander in Chief inaugurated from the beginning what might be termed a "scorched earth" policy. First came an order, on January 11, "to collect all the Beef, Pork, Flour, Spirituous Liquors, &c. &c. not necessary for the Subsistence of the Inhabitants, in all the parts of East Jersey, lying below the Road leading from Brunswick to Trenton." This was followed, on February 3, by instructions for removing out of enemy reach "all the Horses, Waggons, and far Cattle" his generals could lay their hands on. Payment for these items was to be guaranteed, but they might be taken by force from Tories and others who refused to sell. Washington likewise ordered the incessant hampering of all enemy attempts to obtain food and forage. "I would not suffer a man to stir beyond their Lines," he wrote to Col. Joseph Reed, "nor suffer them to have the least Intercourse with the Country."

Conditions being what they were, the success with which these orders were carried into effect is astounding. Gradually, more provisions found their way to Morristown. On the other hand, hardly an enemy foraging party could leave its own camp without being set upon by the Americans. Newspapers, letters, and diaries of the period are filled with accounts of recurrent clashes between detachments of the two armies some involving several thousand men. There were no great casualties on either side, but the Continentals seldom came off second-best. "Amboy and Brunswick," wrote one historian, "were in a manner besieged." Both enemy troops and horses grew sickly from want of fresh food, and many of them died before spring. In New York itself, where Sir William Howe kept headquarters, all kinds of provisions became "extremely dear" in price. Firewood was equally scarce in city and camp.

Thus, by enterprise and daring expedients, Washington greatly discomfited the British Army, reduced still further its waning influence in New Jersey, and simultaneously maintained his own small force in action, preventing the men's minds from yielding to despondence.

THE PROSPECT BRIGHTENS. As spring advanced and roads became more passable, the new Continental levies finally began to come in. "The thin trickle became a rivulet, then a clear stream, though never a flood." By May 20, Washington had in New Jersey 38 regiments with a total of 8,188 men. Five additional regiments were listed, but showed no returns at that time. Moreover, this new army was on a fairly substantial footing, the enlistments being either for 3 years, or for the duration of the war. There was also an abundance of arms and ammunition, including 1,000 barrels of powder, 11,000 gunflints, and 22,000 muskets sent over from France. "From the present information," wrote Maj. Gen. Henry Knox to his wife, "it appears that America will have much more reason to hope for a successful campaign the ensuing summer than she had the last."

Now, with the prospects thus brightening, there might be something of a brief social season to relieve the strain of hard work. Martha Washington had arrived at headquarters on March 15, and other American officers looked forward to being joined by their wives. An intimate word picture of the Commander in Chief in his lighter moods was drawn by one such camp visitor, Mrs. Martha Daingerfield Bland, in a letter written to her sister-in-law from Morristown on May 12: "Now let me speak of our Noble & Agreeable Commander (for he Commands both sexes . . .) We visit them [the Washingtons] twice or three times a week by particular invitation—Ev'ry day frequently from Inclination, he is Generally busy in the fore noon—but from dinner til night he is free for all Company his Worthy Lady seemes to be in perfect felicity while she is by the side of her old Man as she Calls him, We often make partys on Horse backe the Genl his Lady, Miss Livingstons & his aid de Camps . . . at Which time General Washington throws of[f] the Hero—& takes up the chatty agreeable Companion—he can be down right impudent some times—such impudence, Fanny, as you & I like...."

END OF THE 1777 ENCAMPMENT. General Howe had meanwhile determined, as early as April 2, to embark on another major attempt to capture Philadelphia, this time by sea approach. He apparently kept his own counsel, however, and up to the last minute neither the American nor the British Army knew his real intentions. The garrisons at Perth Amboy and New Brunswick left their cramped winter quarters for encampments in the open soon after the middle of May. This colored reports that Howe was about to attack Morristown, or that, while his main force advanced by land towards Philadelphia, a band of Loyalists would march from Bergen into Sussex County to aid a rising of the Tories there.

Made uneasy by these and other British movements, Washington decided that the time had come to leave Morristown. On May 28, therefore, leaving behind a small detachment to guard what military stores were still in the village, he accordingly moved the Continental Army to Middlebrook Valley, behind the first Warchung Mountain a short distance north of Bound Brook, and only 8 miles from New Brunswick. This was a natural position from which the Americans could both defy attack and threaten any overland expedition the enemy might make. Such was the relationship of the two armies as the curtain went up on the ensuing summer campaign. The encampment of 1777 at Morristown had drawn to a close.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |