|

MORRISTOWN National Historic Park |

|

Map of Morristown prepared by Robert Erskine, F.R.S.,

Geographer General of the Continental Army, dated December 12, 1779.

Courtesy of the New York Historical Society.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Jockey Hollow: the "Hard" Winter of 1779—80

INTERMISSION: WAR IN DEADLOCK. Nearly two and a half years passed by before the main body of the Continental Army again returned to Morristown. During that interval the British both captured and abandoned Philadelphia, Burgoyne's Army surrendered to the Americans at Saratoga, and France and Spain entered the conflict against Great Britain. Washington's soldiers had stood up under fire on numerous occasions, besides weathering the winter encampment periods at Valley Forge in 1777—78, and at Middlebrook in 1778—79. On the other hand, the financial affairs of the young United States had gone from bad to worse. Hoped-for benefits from the French Alliance had not yet materialized, and the 3-year enlistments in the Continental Army had only 4 or 5 months more to run before their expiration. Moreover, while the military scales somewhat balanced in the North, the enemy held Savannah, and there were rumors that Sir Henry Clinton, Howe's successor, would soon leave New York by sea to attack Charleston. With the final issue still in doubt, America approached what was destined to be the hardest winter of the Revolutionary War.

MORRISTOWN AGAIN BECOMES THE MILITARY CAPITAL. Such was the general condition of affairs when, on November 30, Washington informed Nathanael Greene, then Quartermaster General, that he had finally decided "upon the position back of Mr. Kembles," about 3 miles southwest of Morristown, for the next winter encampment of the Continental forces under his immediate command. As he later wrote to the President of Congress, this was the nearest place available "compatible with our security which could also supply water and wood for covering and fuel."

The site thus chosen lay in a somewhat mountainous section of Morris County known as Jockey Hollow, and included portions of the "plantation" owned by Peter Kemble, Esq., and the farms of Henry Wick and Joshua Guerin. Some of the American brigades being already collected at nearby posts, Greene at once sent word to their commanders of Washington's decision: "The ground I think will be pretty dry; I shall have the whole of it laid off this day; you will therefore order the troops to march immediately; or if you think it more convenient tomorrow morning. It will be well to send a small detachment from each Regiment to take possession of their ground. You will also order on your brigade quarter master to draw the tools for each brigade and to get a plan for hurting which they will find made our at my quarters."

Simultaneously with this instruction which was dated December 1, Washington himself arrived in Morristown, during a "very severe storm of hail & snow all day." He promptly established his headquarters at the Ford Mansion, presumably at the invitation of Mrs. Theodosia Ford, widow of Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., who was then living in the house with her four children. Morristown had again become the American military capital.

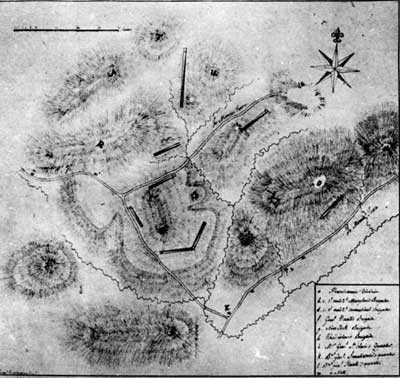

Position of the Continental Army at Jockey

Hollow in the winter of 1779-80.

Drawn by Capt. Bichet de

Rochefontaine, a French engineer.

BUILDING THE "LOG-HOUSE CITY." Events now moved swiftly. Many of the American troops reached Morristown during the first week of December, and the rest arrived before the end of that month. Estimates vary as to their total effective strength, but it was probably not under 10,000 men, nor over 12,000, at that particular time. Eight infantry brigades—Hand's, New York, 1st and 2d Maryland, 1st and 2d Connecticut, and 1st and 2d Pennsylvania—took up compactly arranged positions in Jockey Hollow proper. Two additional brigades, also of infantry, were assigned to campgrounds nearby: Stark's Brigade on the east slope of Mount Kemble, and the New Jersey Brigade at "Eyre's Forge," on the Passaic River, somewhat less than a mile further southwest. Knox's Artillery Brigade took post about a mile west of Morristown, on the main road to Mendham, and there also the Artillery Park of the army was established. The Commander in Chief's Guard occupied ground directly opposite the Ford Mansion. All the positions noted are shown exactly on excellent maps of the period prepared by Robert Erskine, Washington's Geographer General, and by Capt. Bichet de Rochefontaine, a French engineer. A brigade of Virginia troops was included in original plans for the encampment, but it was ordered southward soon after arriving at Morristown, and played no major part in the story here related.

As they arrived in camp, the soldiers pitched their tents on the frozen ground. Then work was begun at once on building log huts for more secure shelter from the elements. This was a tremendous undertaking. There was oak, walnut, and chestnut timber at hand, but the winter had set in early with severe snowstorms and bitter cold. Dr. James Thacher, a surgeon in Stark's Brigade, testified that "notwithstanding large fires, we can scarcely keep from freezing." Maj. Ebenezer Huntington, of Webb's Regiment, wrote that "the men have suffer'd much without shoes and stockings, and working half leg deep in snow." In spite of these handicaps, however, nearly all the private soldiers had moved into their huts around Christmastime, though some of the officers' quarters, which were left till last, remained unfinished until mid-February. A young Connecticut schoolmaster who visited the camp near the end of December described it as a "Log-house city," where his own troops and those of other States dwelt among the hills "in tabernacles like Israel of old." About 600 acres of woodland were cut down in connection with the project.

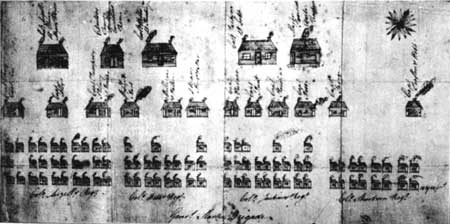

The "hutting" arrangement for General Stark's

Brigade, 1779—80.

From an original manuscript once owned by

Erskine Hewitt, of Ringwood, N. J.

Each brigade camped in the Jockey' Hollow neighborhood occupied a sloping, well-drained hillside area about 320 yards long and 100 yards in depth, including a parade ground 40 yards deep in front. Above the parade were the soldiers' huts, eight in a row and three or four rows deep for each regiment; beyond those the huts occupied by the captains and subalterns; and higher still the field officers' huts. Camp streets of varying widths separated the hut rows. This arrangement is clearly shown in a contemporary sketch of the Stark's Brigade Camp.

|

|

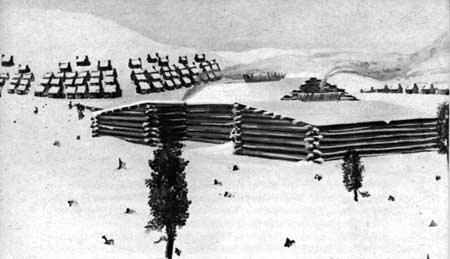

| Reconstructions of typical log huts used by the officers (left) and by soldiers of the line (right) in the winter encampment of 1779—80. | |

Logs notched together at the corners and chinked with clay formed the sides of the huts. Boards, slabs, or hand-split shingles were used to cover their simple gable roofs, the ridges of which ran parallel to the camp streets. All the soldiers' huts, designed to accommodate 12 men each, were ordered built strictly according to a uniform plan: about 14 feet wide and 15 or 16 feet long in floor dimensions, and around 6-1/2 feet high at the eaves with wooden bunks, a fireplace and chimney at one end, and a door in the front side. Apparently, windows were not cut in these huts until spring. The officers' cabins were generally larger in size, and individual variation was permitted in their design and construction. Usually accommodating only two to four officers, they had two fireplaces and chimneys each, and frequently two or more doors and windows. Besides these two main types of huts, there were some others built for hospital, orderly room, and guardhouse purposes. The completed camp seems to have contained between 1,000 and 1,200 log buildings of all types combined.

The Pennsylvania Line campground in 1779—80, with

a hospital hut in the foreground.

From a recent painting in the park collection.

TERRIBLE SEVERITY OF THE WINTER. Weather conditions when the army arrived at Morristown were but a foretaste of what was yet to come, and long before all the huts were up, the elements attacked Washington's camp with terrible severity. As things turned out, 1779—80 proved to be the most bitter and prolonged winter, not only of the Revolutionary War, but of the whole eighteenth century.

One observer recorded 4 snows in November, 7 in December, 6 in January, 4 in February, 6 in March, and 1 in April—28 falls altogether, some of which lasted nearly all day and night. The great storm of January 2—4 was among the most memorable on record, with high winds which no man could endure many minutes without danger to his life. "Several marquees were torn asunder and blown down over the officers' heads in the night," wrote Dr. Thacher, "and some of the soldiers were actually covered while in their tents, and buried like sheep under the snow." When this blizzard finally subsided, the snow lay full 4 feet deep on a level, drifted in places to 6 feet, filling up the roads, covering the tops of fences, and making it practically impossible to travel anywhere with heavy loads.

What made things still worse was the intense, penetrating cold. General Greene noted that for 6 or 8 days early in January "there has been no living abroad." Only on 1 day of that month, as far south as Philadelphia, did the mercury go above the freezing point. All the rivers froze solid, including both the Hudson and the Delaware, so that troops and even large cannon could pass over them. Ice in the Passaic River formed 3 feet thick, and, as late as February 26, the Hudson above New York was "full of fixed ice on the banks, and floating ice in the channel." The Delaware remained wholly impassable to navigation for 3 months. "The oldest people now living in this country," wrote Washington on March 18, "do not remember so hard a Winter as the one we are now emerging from."

LACK OF ADEQUATE CLOTHING. Not even good soldiers warmly clothed could be expected to endure this ordeal by weather without some complaint. How much more agonizing, then, was such a winter for Washington's men in Jockey Hollow, who were again poorly clad! A regimental clothier in the Pennsylvania Line referred to some of the troops being "naked as Lazarus." By the time their huts were completed, said an officer in Stark's Brigade, not more than 50 men of his regiment could be returned fit for duty, and there was "many a good Lad with nothing to cover him from his hips to his toes save his Blanket." As late as March, when "an immense body of snow" still remained on the ground, Dr. Thacher wrote that the soldiers were "in a wretched condition for the want of clothes, blankets and shoes."

SHORTAGE OF PROVISIONS AND FORAGE. Still more critical was the lack of food for the men, and forage for the horses and oxen on which every kind of winter transportation depended. December 1779 found the troops subsisting on "miserable fresh beef, without bread, salt, or vegetables." When the big snows of midwinter blocked the roads, making it totally impossible for supplies to get through, the army's suffering for lack of provisions alone became almost more than human flesh and blood could bear. Early in January 1780, said the Commander in Chief, his men sometimes went "5 or Six days together without bread, at other times as many days without meat, and once or twice two or three days without either. . . . at one time the Soldiers eat every kind of horse food but Hay."

Thanks to the magistrates and civilian population of New Jersey, an appeal from Washington in this urgent crisis brought cheerful, generous. relief. This alone saved the army from starvation, disbandment, or such desperate, wholesale plundering as must have eventually ruined all patriot morale. By the end of February, however, the food situation was once more acute. Wrote General Greene: "Our provisions are in a manner gone; we have not a ton of hay at command, not magazines to draw from." Periodic food shortages continued to plague the troops during the next few months. As late as May 9, there was only a 3-days' supply of meat on hand, and it was estimated that the flour, if made into bread, could not last more than 15 or 16 days. Officers and men alike literally lived from hand to mouth all through the 1779—80 encampment period.

MONEY TROUBLES AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES. The cause of many difficulties faced by Washington that winter appears to have been the near chaotic state of American finances. Currency issued by Congress tumbled headlong in value, until in April—June 1780 it took $60 worth of "Continental" paper to equal $1 in coin. "Money is extreme scarce" wrote General Greene on February 29, "and worth little when we get it. We have been so poor in camp for a fortnight that we could not forward the public dispatches for want of cash to support the expresses." Civilians who had provisions and other necessaries to sell would no longer "trust" as they had done before; and without funds, teams could not be found to bring in supplies from distant magazines. Reenlistment of veteran troops and recruitment of new levies became doubly difficult. Even the depreciated money wages of the army were not punctually paid, being frequently 5 or 6 months in arrears. Dr. Thacher wailed at length about "the trash which is tendered to requite us for our sacrifices, for our sufferings and privations, while in the service of our country." No wonder that desertions soon increased alarmingly, and that many officers, no longer able to support families at home, resigned their commissions in disgust! At the end of May an abortive mutiny of two Connecticut regiments in Jockey Hollow, though quickly suppressed, foreshadowed the far more serious outbursts fated to occur within a year.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |