|

HOPEWELL VILLAGE National Historic Site |

|

A scene in Hopewell Village showing the Big

House, or iron-master's residence, in the right background and the

office and store in the foreground.

Photo by Hallman.

The Iron Plantations

The feudallike colonial iron plantations of Pennsylvania often comprised several thousand acres of land. This was mostly woodland, because charcoal, the fuel used at early ironworks, required enormous quantities of cordwood. Besides the main works, each had its shops, its dwelling houses and gardens, its orchards and grain fields, and sometimes its grist-mills and sawmills. The people literally lived at their jobs, in a compact community which was more or less self-sufficient.

The furnace itself was a truncated pyramid of stone, built near the side of a small hill or bank. Across the opening between was a covered bridge, or "bridge house," over which the "fillers" carried iron ore, charcoal, and limestone to the furnace top, where this "charge" was dumped into the stack. When in blast, the furnace was an impressive sight. Its brilliant flames lit up the night sky for miles around, accompanied by the intermittent roar of the blast. At the other end of the bridge house stood one or more large buildings for storing charcoal. Blast to operate the furnace was furnished by a simple system of machinery geared to a large water wheel. Long ditches, called "races," brought water to the wheel from the surrounding hills or the furnace pond and then conveyed it off again when its power had been spent. Within the casting house, adjoining the furnace on one side, the molten iron was run out into waiting molds of scorched and blackened sand. From the furnace structure, the impure "slag" was drawn off through a "cinder hole" above the hearth, later to be dumped outside. Iron lost in the slag was salvaged by means of a crusher, or "stamping mill," which some furnaces installed near the wheel. Both the ore and slag piles were close to the stack.

A section of the East Head Race and retaining

wall, partially reconstructed by the National Park Service. About a mile

long, it originates in the Baptism Creek area (to right above).

Hopewell Furnace is a quarter of a mile to the west.

Photo by Finch.

Some of these early works consisted only of a furnace or forge, while others had both. The forge, where cast "pig iron" was refined and hammered into blooms, or bars of wrought iron, was generally not far from the village center. This, too, was operated by water power. Within the forge, half-naked men of strong physique swung the white-hot, pasty metal from the hearths to great hammers by means of wide-jawed tongs. Under the steady strokes of these hammers, and amid a shower of sparks, they drew the bars to given sizes. Bar iron from the forges was used by blacksmiths to make tools, implements, and ironware of different kinds.

The Big House stood on a low hill overlooking

the furnace.

Photo by Hallman.

On a low hill, overlooking the furnace or forge, stood the Big House, or ironmaster's residence, surrounded by a garden in which bloomed pinks, lilies, hollyhocks, and other old-fashioned flowers. This building had large rooms, with wide, open fireplaces, and fine furnishings often imported from Europe. Together with the immediately adjacent grounds and outbuildings, it represented all there was of elegance in such a community.

Far less commodious were the workmen's homes, sometimes called tenant houses. They were usually small stone structures or were built of logs and plaster with stone chimneys. All were poorly furnished, without rugs or carpets. Cooking was done at the kitchen fireplace, which also provided heat in winter. Pewter dishes and spoons, iron knives and forks, and wooden bowls and trenchers were the utensils used at meal time. The bedrooms were bare and rarely contained mirrors, tables, drawers, wardrobes, or even chairs.

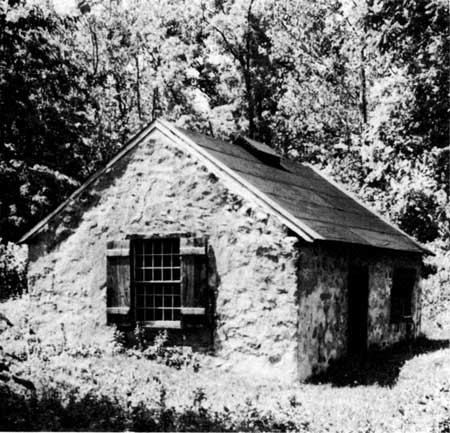

The blacksmith shop at Hopewell Village before

restoration. Here horses and mules were shod, woodchopper's axes

steeled, and metal posts and fixtures for wagons and equipment

made.

There were also subsidiary work buildings. Among these were the blacksmith shop, where draft animals were shod and where necessary tools and other hardware were produced; the wheelwright shop, where the several types of wagons used for hauling were constructed or repaired; and the barns and sheds, where horses, oxen, mules, and other domestic animals were housed.

In the midst of the community was the ironmaster's office and store. Here the business records were kept, and food, clothing, and other supplies sold to the workers. Such stores were necessities because of the long distance from settled boroughs and the money scarcity. The ironmaster credited his workers with their daily earnings on one side of his ledger, and on the other he entered the merchandise they purchased. The latter often included rum, shoes, and other manufactured articles which he received in exchange for iron sent to Philadelphia.

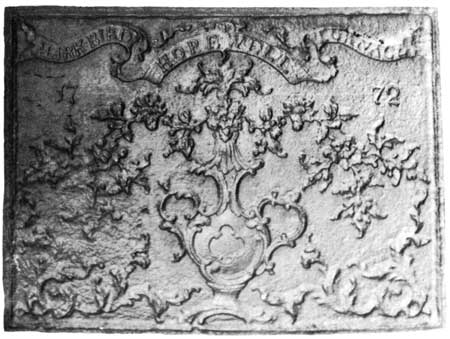

Hopewell stove plate bearing the date 1772.

Nearly all the Pennsylvania furnaces, Hopewell included, cast stoves and hollow ware, such as pots and kettles, in addition to manufacturing pig iron, which was usually their chief product. The first stove castings were flat pieces of iron with tulips, hearts, Biblical figures, and mottoes for decoration. One old stove plate marked "Hopewell Furnace," together with several later (flask cast) Hopewell stoves, can still be seen at Hopewell Village National Historic Site, while other representative castings are in the collections of the Historical Society of Berks County, in Reading, and of the Bucks County Historical Society, at Doylestown, Pa. The early stoves were "open sand" cast; that is, the pattern of the individual plates, carved in relief on mahogany or other hardwood, was impressed directly into the open sand and molten metal poured over it to the desired thickness. "Flask" casting, a more intricate process, came into general practice after the Revolution, especially in the nineteenth century. Coupled with the air furnace and cupola, which resmelted pig iron it made for better grade and finer detail in the finished product.

Iron making was only a part of the work on these plantations. All the cereals were grown, and even flax and hemp were produced. Sometimes a flock of sheep provided wool for the making of warm winter garments. In haytime and harvest the village women and children turned out to work long hours in the fields, gathering most of the crop; and during the winter months they spun thread and wove cloth in their homes. Thus, everyone contributed something to the general economic sustenance.

Social life was a closely knit affair. Although the workers generally led an existence of hard labor, they found some amusement in occasional barn dances, corn huskings, and country parties. Once or twice a year the more fortunate among them traveled to the nearest borough fair. Strong drink dulled the steady grind of toil, for there was much use of rum, whisky, gin, cider, and beer. Many ironmasters found drunkenness a real problem.

Ironmasters possessed fine carriages. This

nineteenth-century tallyho is from the Edward Brooke collection at

Hopewell.

Ironmasters generally lived elegantly, often imitating the life of the English gentry. Many kept a pack of hounds and loved to hunt the fox. Brilliant social gatherings and frequent travels in elegant "pleasure carriages" did much to enliven plantation life. The story of the fabulous "Baron" Henry William Stiegel is well known.

Churches were few in eighteenth century Pennsylvania, so itinerant preachers, traveling the silent forests on horseback, provided what little there was of religious instruction. Education was limited to the children of the ironmaster, and perhaps of the better-paid workmen, and was often supplied by the plantation clerk.

Picturesque roads led from the ironworks to the world outside, with quaint signboards here and there adding to the attractiveness of nature. Along these roads, long before the middle of the eighteenth century, heavy freight wagons, or Conestogas as they later became known, transported merchandise, goods, and produce to and from Philadelphia, and between the boroughs and towns. Pig iron, castings, and bar iron were hauled in open carts over tortuous roads to the main highways. The cost of carriage under these conditions was exceedingly high. One ton of pig iron which sold for £5 at Colebrookdale Furnace cost from £1 to £2 to carry to Philadelphia, only 40 miles away.

Plantations close to rivers, especially those along the Schuylkill, sometimes used them to transport their products to market. But it was not until the early part of the nineteenth century, with the coming of the canals, that waterways came into extensive use.

Few travelers in the eighteenth century visited the iron plantations because of their remoteness from settled areas. Among the few were Peter Kalm, the naturalist, Israel Acrelius, pastor of Christina parish in Delaware, and S. G. Hermelin, metallurgist—all Swedes—as well as Dr. Johann Schoepf, surgeon to Hessian troops during the Revolution to whom we owe much for details and descriptions. Many stories and legends came out of these early plantations, particularly concerning the ironmasters. Most famous perhaps is the legend of the hounds, associated in slightly different variations with a number of furnaces.

One version concerns a despotic, violent-tempered ironmaster much addicted to drink and the hunt. He returned from the hunt one day, according to the story, enraged because his hounds had played him false. Leading his entire pack up the furnace bridge to the blazing tunnel-head, with whip in hand, he drove them one by one into the inferno below. Only his favorite dog remained, quivering with fear. But after a moment s hesitation, he picked her up and cast her bodily into the furnace. A low, fearful moan, and it was all over! The ironmaster never hunted again. Losing all interest in life, he sat day after day before his fireplace, dulling his senses with drink. Then one morning, when he failed to appear, his servants found him dead in bed, whip in hand and eyes set in terror. Many a worker, in the years that followed, swore that on lonely winter nights he had actually heard the baying of the hounds and seen the terribly frightened ironmaster flee before them.

But ironmasters generally were men of good character. They were kindly and took genuine interest in the welfare of their men. The Colemans, Mayburys, Olds, Grubbs, William and Mark Bird, Thomas Potts and his sons and descendents, Stiegel, Rutter, and Nutt—all treated their men sympathetically.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |