|

GETTYSBURG National Military Park |

|

The procession on Baltimore Street en route to the cemetery for

the dedicatory exercises, November 19.

Lincoln and Gettysburg (continued)

DEDICATION OF THE CEMETERY. Having agreed upon a plan for the cemetery, the Commissioners believed it advisable to consecrate the grounds with appropriate ceremonies. Mr. Wills, representing the Governor of Pennsylvania, was selected to make proper arrangements for the event. With the approval of the Governors of the several States, he wrote to Hon. Edward Everett, of Massachusetts, inviting him to deliver the oration on the occasion and suggested October 23, 1863, as the date for the ceremony. Mr. Everett stated in reply that the invitation was a great compliment, but that because of the time necessary for the preparation of the oration he could not accept a date earlier than November 19. This was the date agreed upon.

Edward Everett was the outstanding orator of his day. He had been a prominent Boston minister and later a university professor. A cultured scholar, he had delivered orations on many notable occasions. In a distinguished career he became successively President of Harvard, Governor of Massachusetts, United States Senator, Minister to England, and Secretary of State.

The Gettysburg cemetery, at the time of the dedication, was not under the authority of the Federal Government. It had not occurred to those in charge, therefore, that the President of the United States might desire to attend the ceremony. When formally printed invitations were sent to a rather extended list of national figures, including the President, the acceptance from Mr. Lincoln came as a surprise. Mr. Wills was there upon instructed to request the President to take part in the program, and, on November 2, a personal invitation was addressed to him.

Throngs filled the town on the evening of November 18. The special train from Washington bearing the President arrived in Gettysburg at dusk. Mr. Lincoln was escorted to the spacious home of Mr. Wills on Center Square. Sometime later in the evening the President was serenaded, and at a late hour he retired. Ar 10 o'clock on the following morning, the appointed time for the procession to begin, Mr. Lincoln was ready. The various units of the long procession, marshaled by Ward Lamon, began moving on Baltimore Street, the President riding horse back. The elaborate order of march also included Cabinet officials, judges of the Supreme Court, high military officers, Governors, commissioners, the Vice President, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Members of Congress, and many local groups.

Difficulty in getting the procession under way and the tardy return of Mr. Everett from his drive over the battleground accounted for a delay of an hour in the proceedings. At high noon, with thousands scurrying about for points of vantage, the ceremonies were begun with the playing of a dirge by one of the bands. As the audience stood uncovered, a prayer was offered by Rev. Thomas H. Stockton, Chaplain of the House of Representatives. "Old Hundred" was played by the Marine Band. Then Mr. Everett arose, and "stood a moment in silence, regarding the battlefield and the distant beauty of the South Mountain range." For nearly 2 hours he reviewed the funeral customs of Athens, spoke of the purposes of war, presented a detailed account of the 3-days' battle, offered tribute to those who died on the battlefield, and reminded his audience of the bonds which are common to all Americans. Upon the conclusion of his address, a hymn was sung.

This is the only known close, up photographic view of the

rostrum (upper left) at the dedication of the National Cemetery.

The view shows a part of the audience which was estimated at

15,000.

Bachrach photograph.

Then the President arose and spoke his immortal words:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom— and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

A hymn was then sung and Rev. H. L. Baugher pronounced the benediction.

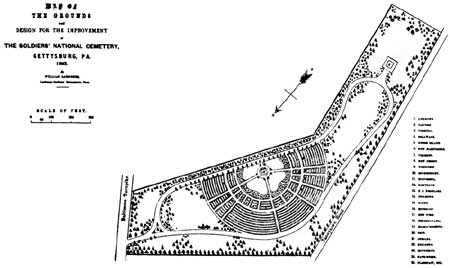

Plan of the National Cemetery drawn in the autumn of 1863 by the

notable landscape gardener, William Saunders.

(click on image above for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |