|

GETTYSBURG National Military Park |

|

Lincoln and Gettysburg (continued)

GENESIS OF THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS. The theme of the Gettysburg Address was not entirely new. President Lincoln was aware of Daniel Webster's statement in 1830 that the origin of our government and the source of its power is "the people's constitution, the people's government; made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people." Lincoln had read Supreme Court Justice John Marshall's opinion, which states: "The government of the Union . . . is emphatically and truly a government of the people. . . . Its powers are granted by them and are to be exercised directly on them, and for their benefit." In a ringing anti-slavery address in Boston in 1858, Rev. Theodore Parker, the noted minister, defined democracy as "a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people." On a copy of this address in Lincoln's papers, this passage is encircled with pencil marks. But Lincoln did not merely repeat this theme; he transformed it into America's greatest patriotic utterance. With the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln gave meaning to the sacrifice of the dead—he gave inspiration to the living.

Rather than accept the address as a few brief notes hastily prepared on the route to Gettysburg (an assumption which has long gained much public acceptance), it should be regarded as a pronouncement of the high purpose dominant in Lincoln's thinking throughout the war. Habitually cautious of words in public address, spoken or written, it is not likely that the President, on such an occasion, failed to give careful thought to the words which he would speak. After receiving the belated invitation on November 2, he yet had ample time to prepare for the occasion, and the well-known correspondent Noah Brooks stated that several days before the dedication Lincoln told him in Washington that his address would be "short, short, short" and that it was "written, but not finished."

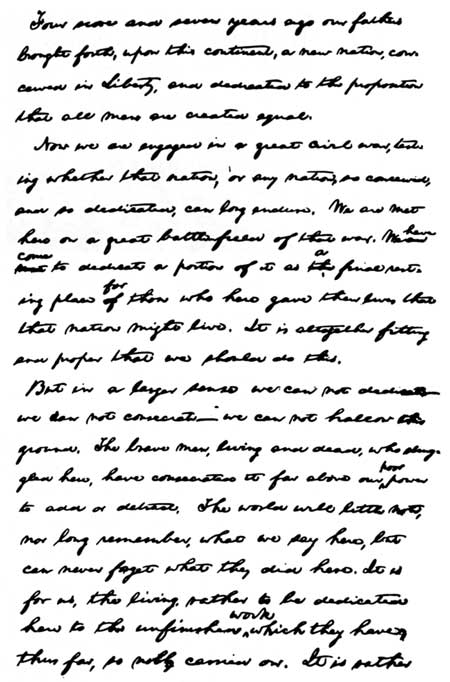

First page of the second draft of the Gettysburg Address. This

copy, made by Lincoln on the morning of November 19, was held in his

hand while delivering his address.

Reproduced from the

original in the Library of Congress.

THE FIVE AUTOGRAPH COPIES OF THE GETTYSBURG

ADDRESS. Even after his arrival at Gettysburg the President

continued to put finishing touches to his address. The first page of the

original text was written in ink on a sheet of Executive Mansion paper.

The second page, either written or revised at the Wills residence, was

in pencil on a sheet of foolscap, and, according to Lincoln's secretary,

Nicolay, the few words changed in pencil at the bottom of the first page

were added while in Gettysburg. The second draft of the address was

written in Gettysburg probably on the morning of its delivery, as it

contains certain phrases that are not in the first draft but are in the

reports of the address as delivered and in subsequent copies made by

Lincoln. It is probable, as stated in the explanatory note accompanying

the original copies of the first and second drafts in the Library of

Congress, that it was the second draft which Lincoln held in his hand

when he delivered the address.

Quite opposite to Lincoln's feeling, expressed soon after the delivery of the address, that it "would not scour," the President lived long enough to think better of it himself and to see it widely accepted as a master piece. Early in 1864, Mr. Everett requested him to join in presenting manuscripts of the two addresses given at Gettysburg to be bound in a volume and sold for the benefit of stricken soldiers at a Sanitary Commission Fair in New York. The draft Lincoln sent became the third autograph copy, known as the Everett-Keyes copy, and it is now in the possession of the Illinois State Historical Library.

George Bancroft requested a copy in April 1864, to be included in Autograph Leaves of Our Country's Authors. This volume was to be sold at a Soldiers' and Sailors' Sanitary Fair in Baltimore. As this fourth copy was written on both sides of the paper, it proved unusable for this purpose, and Mr. Bancroft was allowed to keep it. This autograph draft is known as the Bancroft copy, as it remained in that family for many years. It has recently been presented to the Cornell University Library. Finding that the copy written for Autograph Leaves could not be used, Mr. Lincoln wrote another, a fifth draft, which was accepted for the purpose requested. It is the only draft to which he affixed his signature. In all probability it was the last copy written by Lincoln, and because of the apparent care in its preparation it has become the standard version of the address. This draft was owned by the family of Col. Alexander Bliss, publisher of Autograph Leaves, and is known as the Bliss copy. It now hangs in the Lincoln Room of the White House, a gift of Oscar B. Cintas, former Cuban Ambassador to the United States.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |