|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

An Obsession to Create

Thomas Edison was not born to a life of ease. He was pre-Civil War, small town, middle-class America. He may have been a genetic accident, for his precursors showed little of the potent drive or sponge-like mental powers of the boy who devoured the Detroit Free Library with only three months of school learning.

Financial insecurity was a way of life to the Edison family. To his mother, Edison attributed the "making of me." To his ne'er-do-well father, who once beat him and shamed him unmercifully in the town square, he displayed great generosity and affection in his later life.

Drive he had from the earliest—enormous power to resist physical and mental fatigue and a single-mindedness that more "well-adjusted" folk could never sustain. By his teens he was operating a lucrative business of his own by selling newspapers and goodies to passengers on the Grand Trunk Railroad in Michigan. His very youthful fascination for chemistry persisted in the lab-on-wheels he made in the corner of a stuffy and creaking baggage car.

During his teens he became nearly totally deaf by accident or illness. When he began a new career as a telegrapher at 16, the deafness certainly was a disadvantage, though at times he claimed it allowed him to concentrate and not be distracted by other telegraphic circuit noises.

In his late teens Edison the telegrapher was Edison the rebel. He could not abide the discipline and strictures imposed by others. He was an expert operator, but the boredom of the work drove him to break the rules, sometimes for pure amusement. Being fired or quitting jobs was a way of life. He moved from town to town, working in such places as Fort Wayne, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Nashville, Memphis, Louisville, and Boston.

Telegraphy problems consumed his interest in those years. He spent hours trying to work out ways to improve circuits, to automate, to increase the reach of that singing wire. In almost a fairy-tale fantasy he struck it rich at 23 in New York by inventing a vastly improved stock ticker, close cousin of the telegraph. He was rich, for a while, and he was on his way to a creative half century of life.

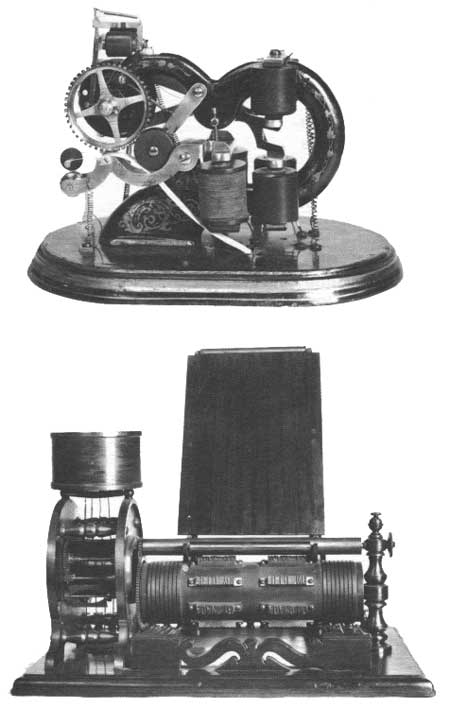

The electrographic vote recorder, below, and the stock ticker were Edison's first two inventions. He could not sell the vote tabulating machine, but he received $40,000 for his initial stock ticker improvements. He used most of that money to buy the building on Ward Street in Newark in which he produced the stock machines and numerous other inventions. |

In his twenties, communications problems continued to fascinate him. In those years, John Ott, Charles Batchelor, and John Kruesi joined his staff in Newark, N.J., and gave him the dedicated craftsmen and skilled artisans he needed to translate his many ideas into objects.

Innumerable small improvements in telegraphy apparatus came out of the shop where the money making stock ticker was produced. He worked hard at developing a two-message-at-a-time-on-one-wire device called a Duplex and was temporarily crushed when Joseph B. Stearns finished his improvement first and beat him to the Patent Office.

Edison later pursued a long-held dream of perfecting a device which would handle four messages at one time on the same wire. It was the Edison method: try, change, try, change, again and again. He had to complete the Quadruplex to his own great satisfaction and profit, for Western Union was as anxious as the young inventor to see this device materialize.

The establishment selected was wholly unpretentious and devoid of architectural beauty, but it was centrally located in Ward street, Newark, supplied with a comparative abundance of facilities and manned by a force of three hundred.... W. K. L. and Antonia Dickson, The Life and

Inventions of Thomas Alva Edison, 1894

|

They saw it finished in 1874, and fortune, fame, and future were made almost certain for Edison. He was becoming experienced at surviving the patent lawsuits, lies, idea-thievery and humbug that then typified the industrial life of America.

Years earlier, a more idealistic Edison had produced a clever electric vote tabulator for use by legislative bodies. But the members of those institutions did not want the device; it was too efficient, it would prevent dealing while voting. He rarely made the error of invention-for-its-own-sake again. Instead, he set his sights on fulfilling both the desire to create and the very human passion for fame and fortune.

America's inventors of the day were a rough and tumble lot. They bore little resemblance to such scientists of an earlier day as Joseph Henry, who was so self-effacing, scholarly, and gentlemanly that he would not lower himself to making money on a new idea by obtaining a patent. Henry considered science a Christian calling, and if the 19th century witnessed a dichotomy between pure and practical science it was best illustrated by the contrast between Henry on the one hand and Goodyear, Bell, Morse, McCormick, and Edison on the other.

Alexander Graham Bell was a contemporary of Edison and a competitor in the communications field. He was born the same year as Edison and lived nearly as long. Bell had an intense interest in teaching the deaf. To communicate with them he envisaged an "harmonic telegraph" and was fascinated by reports of Stearns' duplex telegraph in 1872. His wrestling with perfection problems brought him to envision further the manufacture of a "phonoautograph," a device which would translate sound waves into a meaningful pattern of curves on a smoked glass. All these hopes, combined with thousands of hours of work, brought Bell a patent in 1876 for the first device to transmit human speech by electricity—the telephone. Only a few hours after Bell filed for a patent, Elisha Gray filed a very similar sketch. Bell made a fortune; Gray did not.

One suspects some understandable jealousy on Edison's part regarding Bell's success. Edison had tinkered in the field, and Western Union soon engaged him to invent a better telephone. Edison was confident he could do much more with Bell's very crude instrument; its tiny squeaking was human speech only to those with vivid imaginations.

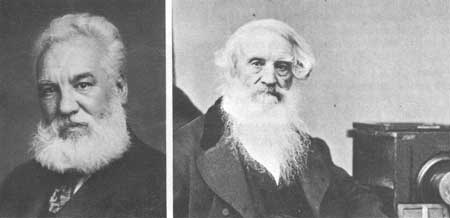

Alexander Graham Bell, left, and Samuel F. B. Morse were like Edison in that they concentrated their inventive energies on goods which would ease man's daily toil. Bell is best known for inventing the telephone and Morse for the telegraph. |

Edison's improvement, a carbon transmitter combined with Bell's magneto receiver, was a much more distinct instrument. But Edison was just one of many inventors seeking to improve Bell's instrument, and only a few weeks earlier Emile Berliner got the jump on some aspects of Edison's improvements in a caveat he filed with the Patent Office. After a 15-year court fight Edison was credited with developing the successful carbon transmitter.

Bell's conflict with Gray and Edison's with Berliner were typical of those days. Inventors were competing with each other all the time. They often would take another's idea and try to refine or change it in such a way that they could call the idea their own. Major firms such as Western Union and Bell Telephone would buy the ideas and in turn compete. It was the era of idea thievery, and great profits were the stakes. Edison admitted to being among the most vigorous of the idea thieves, but he added, one imagines with a twinkle, "I know how to steal."

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |