|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

Crucibles of Creativity: The Labs(continued)

In 1878, the pressures of mixing inventing with manufacturing were crushing Edison. He got away from it all briefly on a trip to Wyoming. He had invented a device for making precise heat measurements and wanted to test it during an eclipse of the sun. His experiments were not successful, but the respite from the lab and stimulating conversation rejuvenated his fatigued spirit. He returned to New Jersey determined to realize the dream of a practical electric lighting system for the homes of America.

While dabbling in the field the year before, he had met with all the frustrations well known to others who tried before him. Now, refreshed, he turned his immense energies to the problem. Early in his experiments he rejected the arc light as unworkable for home use and decided he had to match the gaslight advantages of infinite subdivision of power and controlled brilliance. It was a formidable challenge, even for Edison.

The Search For The Right Filament More Information |

He shrewdly calculated the economic aspects of gas versus electric illumination. He became a skilled gas engineer. He developed an intensive and extensive prospectus for an electric light industry before the fact of invention; he had not forgotten the folly of his vote tabulator. A masterful publicity campaign gained him the backing of men like J. P. Morgan and William Vanderbilt.

The laboratory phase of the search for a practical incandescent lamp began in earnest. Teams searched the world for filament materials. He tried many substances under all possible circumstances. The results were distressing. He early saw the need for developing a good vacuum in the lamp bulb and began to make calculations which would lead to the parallel circuitry used in homes today. He was reliving the frustrations of such lighting pioneers as Charles Brush, William Sawyer, and Joseph Swan.

The quest for an electric lamp and all the devices and machinery needed to make it useful in the home brought young Francis Upton to the Menlo Park staff. A theoretical mathematician, Upton was to prove invaluable in the light experiments, despite the constant teasing of his math-poor boss.

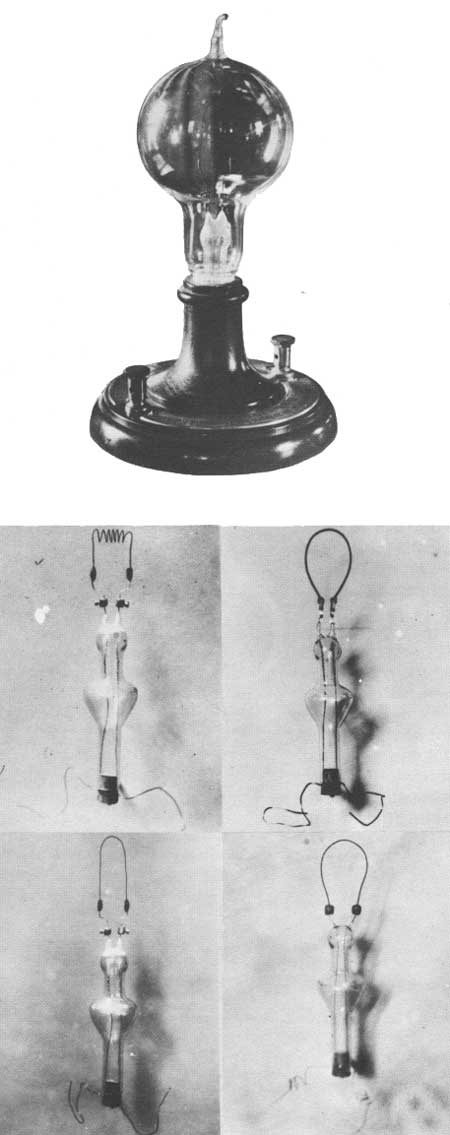

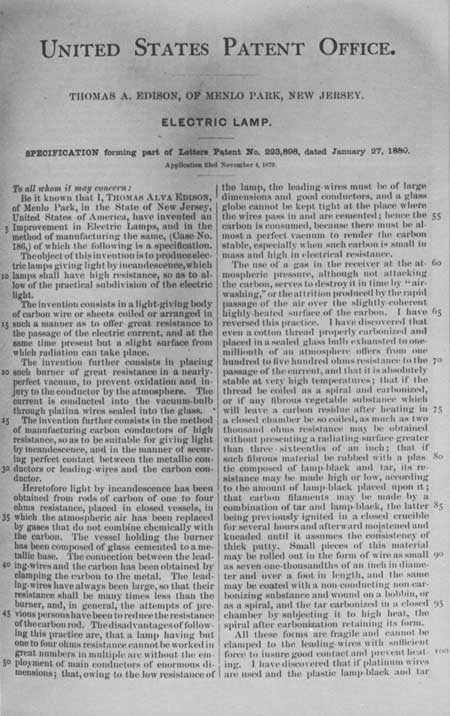

Beneath a replica of the first successful incandescent lamp are four experimental filaments. They are, clockwise from top left, carbonized spiral graphite sewing thread, carbonized bristol cardboard, carbonized cotton sewing thread, and carbo-hydro. A carbonized cotton sewing thread was used in the memorable test, October 19-21, 1879. |

For about a year Edison agonized with the bulb design and distribution system. His staff was overworked and hard pressed. Finally he narrowed his search for the proper filament to carbonized cotton threads. Starting on October 19, 1879, a bulb burned nonstop for 40 hours, burning out only when Edison turned up the power level. A new age was born. The Wizard of Menlo Park, as he was touted in the press of the day, had taken the shattered dreams of other men and made them work. He had made his most monumental contribution to American science and technology.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |