|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

Crucibles of Creativity: The Labs (continued)

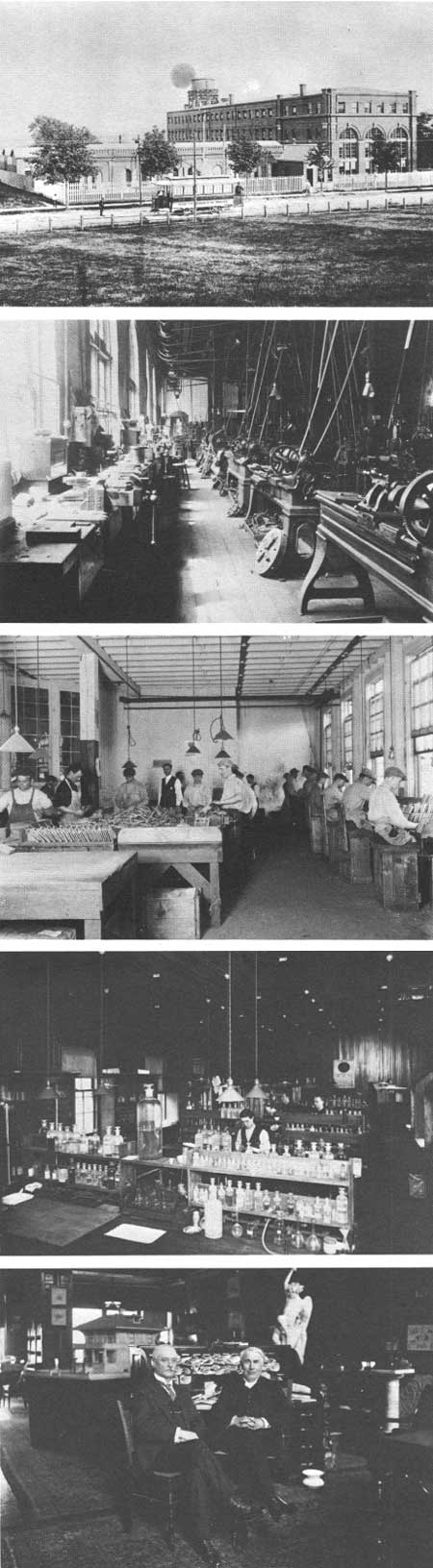

West Orange, N.J., was "country" in those days. Edison selected this sparsely populated and quiet town to be the site of a new "invention factory" 10 times the size of Menlo Park. The lab, just a mile from Glenmont, was finished in 1887. It was magnificent. All of the main structures were brick, and the largest, Building 5, had three stories with a total of 30,000 square feet of floor space. In Building 5 were shops containing very heavy and precise machinery of many kinds, a library which eventually had 10,000 books, a music room, a darkroom, and a stockroom replete with the most common and most scarce substances of the natural world.

They Worked For Edison At West Orange More Information |

One-story brick buildings laid out at right angles to No. 5 contained the latest equipment for making precise electrical measurements, carrying out complex chemical experiments, and developing prototype equipment parts. A picket fence enclosed the whole complex to protect the secrecy of experiments, and guards admitted visitors by invitation only. One time Edison himself was refused entrance until an assistant went to the gate to identify him.

The intimacy of Menlo Park was gone. Instead of the dozen or so top assistants, Edison now had about 50. He was further removed from the front-line action, and management chores in his growing manufacturing plant took much of his time. Although he sometimes secreted himself with an assistant in a section of the lab to work out some thorny problem, he spent much time at his desk in the huge library. Often lab section heads and manufacturing management people reported to him there.

"The chemical room is a favorite of Edison," according to the Dicksons, "and here he often may be found, draped in an unsightly toga, the groundwork of which may once have been brown, but which is now embellished with strange devices in magenta, arsenic-green and yellow, the result of divers chemical catastrophes. He seems to be inhaling the evil smells with a gusto . . . ." |

Though larger, the West Orange lab was like its predecessor at Menlo Park in that it was the only private research lab devoted to a broad spectrum of invention and not the slave of one industry. Josephson wrote that "The strategic importance of Edison's original model of the private research center, as the handmaiden of technology, was quickly grasped by the masters of some of our large industrial corporations." These new company labs, like Westinghouse and Bell, were not successful for some time, perhaps because they did not have an Edison at the helm.

The main building at West Orange contained offices, a library, a large stock room, and all kinds of experimental rooms. Both the first and second floors had a machine shop. Many of the various experiments and production activities were carried out in buildings near the compound or in other locations, such as the primary battery assembly plant and the Edison Chemical Works lab in Silver Lake, N.J. At his desk in the library, Edison often met with top assistants and with guests, in this case Rudolph Diesel, developer of the compression-ignition engine. |

The road to a new Edison product was a fairly standard one although experimentation toward one goal often would reveal something so new that the offshoot would prove more important than the original. The original idea came most often from the fertile mind of Edison, the result of creative synthesizing. Many times other theoreticians on the staff would assist in the idea formulation phase. Then the idea, embodied in rough sketches and notes, would be reduced to drawings and plans by others. Slowly a prototype model would be detailed on paper. Then the plan would go to the shops for building and to the field or lab for testing. For every successful improvement or innovation there were many dead ends and failures.

Edison gathers with his top employees outside the laboratory in July 1893. The men, front row from left, are Charles Brown, J. Gladstone, Thomas Maguire, John Ott, Edison, Charles Batchelor, Walter Mallory, J. Randolph, J. Harris; second row, A. Stewart, W. Miller, Jonas Aylsworth, J. Marshall, Arthur Kennelly, P. Kenny, W. K. L. Dickson, T. Banks, H. Miller; third row, S. Burn, Charles Wurth, F. Phelps Jr., Fred Ott, E. Thomas, R. Lozier, William Heise, W. Logue, H. Gagan, A. Wangemann; fourth row, L. Sheldon, R. Arnot, C. Kaiser, J. Martin, H. Reed, C. Dally, F. Devonald, and A. Thompson |

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |