|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

Crucibles of Creativity: The Labs (continued)

The Edison of middle age tended to be less flexible than Edison the young man. He was inclined to dismiss competitors' innovations which in his early days he would have "borrowed" and refined. One cannot escape the conclusion that despite all its wonderful equipment, materials, and staff, the West Orange lab simply never approached Menlo Park in degree of creativity.

Fierce competition forced him to turn his attention once again to the phonograph. He saw others close to reaping profits from their versions of home entertainment phonographs. So, during the 1880's and 1890's, he developed improved model after improved model of the Edison phonograph. The competition was growing stiff, and holding a large share of the market was Edison's lifeline to solvency. He held on to it tenaciously.

Though the phonograph business demanded the attention of a large part of his staff, it did not completely subvert the original intent of the lab. Experimental products in diverse fields were produced. Some succeeded, but many failed.

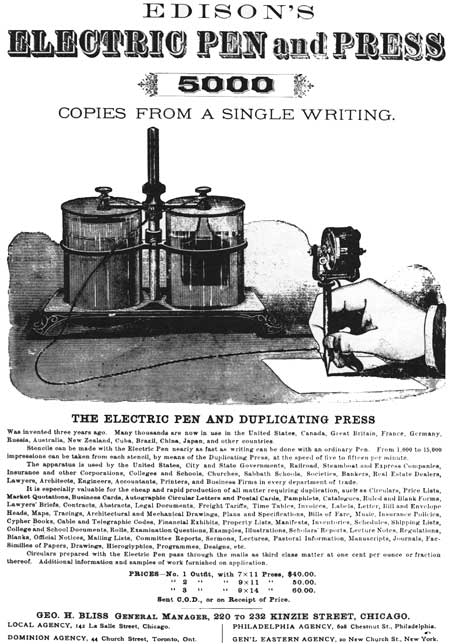

One of Edison's lesser known inventions was the electric pen and press, touted here in an advertisement. Two offshoots of the entertainment phonograph were the dictating machine and the talking doll. The doll did not sell very well, but that failure was minor when compared to the millions of dollars involved in his unsuccessful New Jersey ore-mining operation (below). |

This was a trying period for Edison. He was losing his firm grip on the electrical business. More and more people, such as George Westinghouse and Elihu Thomson, were competing with him. Edison stubbornly stuck with his direct-current system and openly sparred with Westinghouse, an alternating-current proponent. Edison's factory payrolls, meanwhile, were constantly rising and getting more difficult to meet. He decided to bolster the electrical business by joining forces with a financial syndicate. The Edison Electric Light Company became the central part of Edison General Electric Company. Edison still had some say in the affairs of the firm, but against his wishes he soon lost most of that power when Edison General Electric merged with its chief competitor, Thomson-Houston. The firm was called the General Electric Company. Edison's name had been dropped.

Edison was dejected by all these financial dealings and even before the final merger decided to leave his electric power involvements and immerse himself in a new search. By 1890 the high-grade iron ore in the eastern States had been exhausted and machinery had not been developed to economically utilize the great quantities of lower-grade ore. Edison decided to find a way. He purchased a large area near Ogdensburg, N.J., and constructed a huge facility for crushing, processing, and extracting iron. The facility was supposed to smash and crush boulders the size of an upright piano. Full of problems and breakdowns, it drained the money and time of Edison for years. He sank $2 million into this venture and was in debt for hundreds of thousands more. In 1899 he was laboring to keep his constantly improving machinery operating, trying to get ahead of the heavy losses he was taking. But one day Charles Batchelor brought him the news that the vast Mesabi range deposits in the Midwest were to be extracted by open-pit mining and that economical transportation eastward on the Great Lakes had been made feasible. Iron ore fell to $2.65 a ton in Cleveland. Edison's New Jersey & Pennsylvania Concentrating Works was ruined; the company was broke.

New Jersey ore-mining operation. |

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |