|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

Crucibles of Creativity: The Labs (continued)

Having recovered quickly from the defeat and failure of a decade of striving in iron mining, Edison decided in 1900 to make a better battery.

Huge and efficient generators of electricity were already in use. Called dynamos, they were progeny of the first 90 percent efficient generator developed by Edison—the "long-waisted Mary Ann." A necessary auxiliary to these dynamos was a means of storing power for a long period. The storage battery was in common use, but it was of lead-acid construction, heavy, and destroyed itself in rather short order. Edison, the master innovator in the power field, saw the need for a battery which would last longer and be lighter. He believed that electric motors were superior to gasoline engines for use by the infant auto industry and that a better battery would make electric cars truly competitive.

By 1901 the West Orange lab was gearing up for the new quest. He hired a staff of about 90 men under a chief chemist, gathered a huge assortment of materials to be tested by the Edison method, and began the search. For years they experimented intensively. Always, it seemed that when they had developed one characteristic in a battery which was desirable they found another which was not.

Edison obtained many patents during this period before finally coming up with a nickel-iron-alkaline battery. It was a great improvement over lead-acid types in several ways. It was slow to decompose and it was light. It also was reversible; that is, upon charging, the battery would reassume its internal physical structure. It held a charge for an extremely long time without recharging, but it was expensive and could not deliver enough power for its weight to make it useful in all-electric autos. Nor could it provide the heavy initial current needed to start a gasoline buggy.

Despite these problems, the nickel-iron-alkaline battery was a magnificent example of the Edison quality and was used in mining and railway devices. Some Edison batteries have been known to last a generation. He could well be proud of his handiwork.

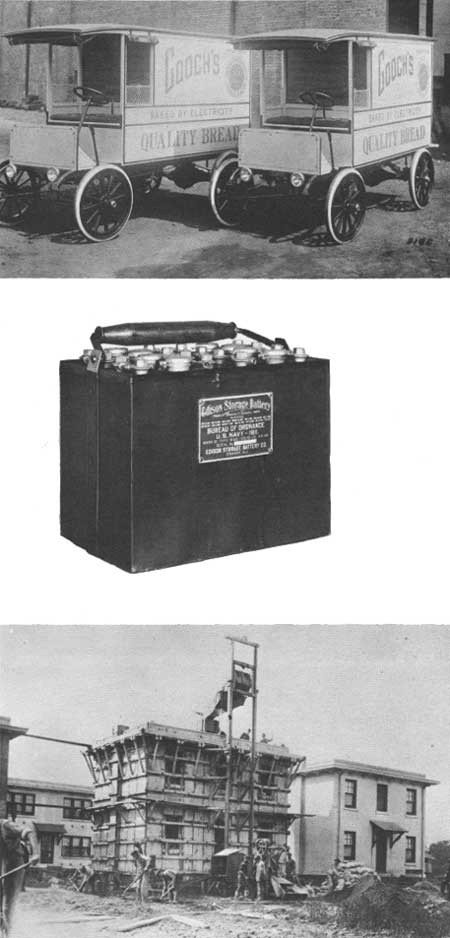

A bakery in Lincoln, Nebr., not only used Edison storage batteries to power its trucks but advertised its then novel way of baking bread, by electricity. While working on the nickel-iron-alkaline storage battery in the early 1900's, Edison also produced poured cement houses. |

A foray into the world of building construction consumed his interest for a while. He wanted to utilize the then idle heavy machinery at Ogdensburg. He converted it to manufacture cement and built a complex of factory buildings around the old lab entirely of reinforced concrete. He tried to interest the public in prefabricated, poured homes, remarkable structures which, when iron molds were removed, contained stairways, rooms, halls, cellars, and conduits—all of concrete. But the idea was too advanced for that day, and Edison gave it up.

As he took up new experiments and invented various devices, Edison would form manufacturing companies. He started almost 200 companies and corporations. Today power production utilities across America bear his name in the fashion of Consolidated Edison of New York City. McGraw-Edison Corporation is the direct descendant of Thomas A. Edison Industries, Inc., and only in 1972 did the corporation vacate the reinforced concrete production facilities around the red brick lab on Main Street in West Orange. And, of course, General Electric traces its lineage to him.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |