|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

Crucibles of Creativity: The Labs (continued)

The Phonograph Became An Industry More Information |

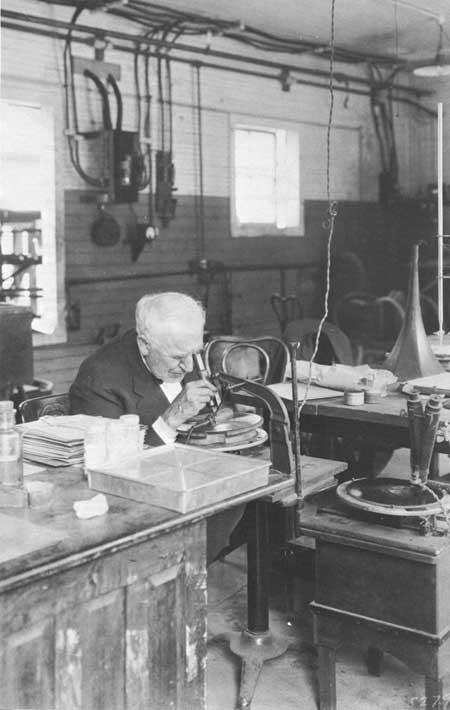

Through all the years of travail and failure which characterized many of Edison's quests at the West Orange lab, one invention, the phonograph, was always in various stages of development. Phonographs bearing the Edison name were refined there for 42 years from the earliest cylinder models to disc console models of remarkable fidelity for non-electronic devices. The competition was fierce during this time. Chichester Bell and Charles Tainter's Graphophone, Emile Berliner's Gramophone, the Victor Talking Machine Co.'s Victrola, and other devices were competing with Edison's phonograph. Edison's various models held the quality edge, but toward the end of his life the new processes and devices which he had resisted began to erode this predominance.

Beginning in 1912, Edison produced disc records, which he maintained were not as good as the cylinders |

Nonetheless, the phonograph served Edison the middle-aged and older man in much the same way the stock printer served Edison the young man; it was like a steady job, always there, supporting him when a spectacular venture would fail or be only partially successful. Competition constantly forced an upgrading of the Edison product and kept lab personnel challenged and innovative for almost a half-century. And this omnipresent, close-knit interaction of research and manufacturing exemplified the most basic and perhaps most important Edison invention of all, the prototype modern industrial research laboratory.

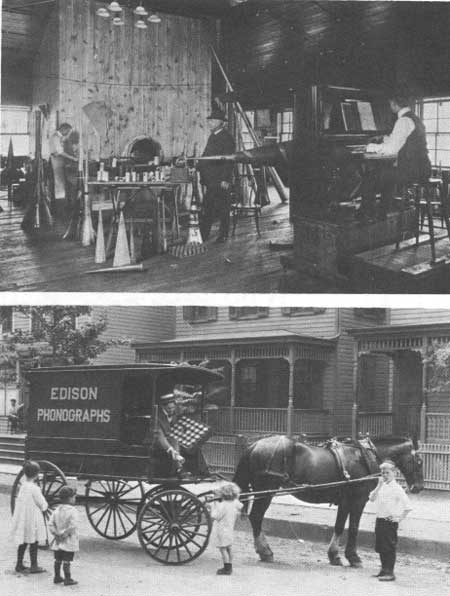

Recording George Boehme on the piano in the music room on the top floor of Building 5 at West Orange, are Albert Kipfer, (top) and A. Theodore E. Wangemann, the sound engineer. Records and cylinder phonographs, such as the Amberola, were sold door to door in some places (bottom). |

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |