|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

He Made Science Serve

Thomas A. Edison has been characterized as a lone wolf in post-Civil War America's technological revolution. Popular literature of his day tended to paint him in the colors of the rugged loner, sort of proto-Tom Swift, a frontiersman of science. In fact, this dramatic portrait is nonsense.

As Josephson suggests, mathematician Norbert Wiener's description of Edison as a "transitional figure" in American science is much closer to the truth. Edison's organization of artisans, technicians, and trained scientific theoreticians became a model for the complex research laboratories of the 20th century. The development of the Edison inventions depended not on high insights alone but on the brainpower, sweat, and imagination of a highly motivated team. The team at the invention factory helped make the Edison name the popular and real equal of a Roosevelt, a Wilson, a Grant, a Pershing, a Ford, a Cobb, a Fairbanks.

In his later years, Edison many times closed his mind to constructive criticism from his assistants. Edison got so he would not accept much of the advice he received from his employees and even his sons. He became more crusty and withdrawn. The result was that the invention factory lost much of its relevance and fell back from the vanguard of American technology during the 20th century. Creativity decreased as his visionary scope narrowed.

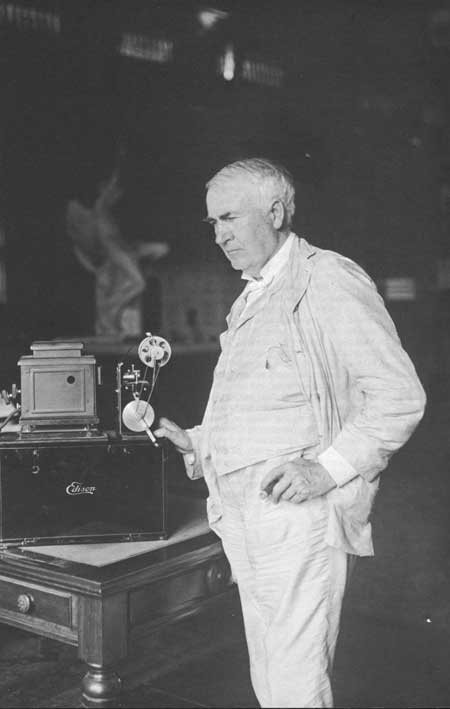

Edison examines the Projecting Kinetoscope, or movie projector, in the library of his West Orange laboratory. |

Edison was no social reformer, but his concept of invention for useful and practical purposes, assisting in the alleviation of human labor and boredom, was a humanizing influence on American science. In subordinating invention to commercial and popular need, Edison advanced his own for tunes and the quality of life in a nation of men, women, and children barely liberated from dawn-to-dusk labor in field, sweatshop, and kitchen.

The needs of a people and a nation and his own almost mystical unquenchable obsession to create, to improve, and to build were Edison's taskmasters. Few men have ever worked harder and longer for any master anywhere. If he did not share the virginal and pristine ethics of a Faraday or Henry in his approach to invention, he did worlds more than both men to bring increased pleasure and comfort to the people of his day. He made the business of inventing both productive and less hazardous through both the genius he debunked and through the hard work and sweat he claimed.

And he put to rest forever the assertion of an earlier day that invention was a "divine accident."

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |