|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Who am I? Reflections on the Meaning Of Parks on the Occasion of The Nation's Bicentennial |

|

For many years our country, and to some degree the entire world, has been buying physical comforts on a credit card, with the fond hope that the creditor might forget to render the bill. Not so. Nature is a lenient creditor of man, infinitely patient with his impertinent behavior, but insistent upon the ultimate payment. The bill has now come in.

People throughout the land are calling for an end to our pollution of the air and the waters of rivers and lakes—and thus even of the oceans—all brought about by an ever-increasing technological proliferation based upon the illusion that growth is good simply because it is growth. Even economists are beginning to doubt that old fable.

But aside from the conquest of water and air pollutions, and we surely have the technological skills for that, the moment of truth has arrived about many other things menacing to human life upon our planet, which we have been viewing through roseate spectacles. There is the pressing problem of our cities, with their slums and the neuroses brought on by noise, foul air, great stretches of ugliness almost beyond belief, and the tendency toward violence and abnormality caused by mere crowding. Already more than 70 percent of our population is urban or suburban, and the people who study such things expect this trend to continue rather than diminish.

Admiral Rickover has said that "there is a tendency in modern thinking to ascribe to technology a momentum of its own—beyond human direction or restraint." Do we confess that the machine, which has been the source of so many benefits to us, has become our master, taking away from us the choices and diversities that make human life a joy instead of a dull and meaningless chore?

Since the roof suddenly seems to be falling in upon us, it is natural to look for the villain in the drama. Who did this to us? Was it science? Was it the applied scientist or engineer who took the discovery of natural truths and utilized them for devices of comfort and luxury? Or are all our machines innocent in themselves and a menace only when they reach a certain magnitude?

One of the ancient Greek philosophers may have given us the answer when he announced his maxim "Nothing in Excess." There may, indeed, be a "golden mean," beyond which man finds he has trapped himself by his own genius.

In searching for the answers—and they must be found—there are two aspects of the situation that give us grounds for optimism. One is that we are now keenly alerted to the dangers. For years men and women of foresight have issued warnings about the perils which lie down the road we are traveling. They were regarded as dreamers of nightmares. Now, in newspapers and magazines, in books and on television, the alerts are sounding. The crisis has become a matter of common concern.

The other aspect is the support of the people. Without their help we can do nothing. With it, we can do anything. In a government of the people, this is an eternal truth and perhaps the only way out of our predicament. The majority of the citizens must apprehend, sympathize, and commit themselves to action.

Here, then, is the reason for this present brief message. It is undeniable that, as a people, we have drifted away from the feeling of our unity with nature—and with each other. We have ceased to wonder. We have forgotten, in the enjoyment of an apparent affluence, to ask ourselves the question, in meditative moments, Who am I? Where did I come from? What is my relationship to the natural environment and to the social scheme? Physically, and as a strange and wonderful product of the evolution of mind, what are my limitations? If we do not know our limitations, our aspirations will sour.

In the National Park System, the nearly 300 sites—areas preserved for beauty, for superlative exhibitions of natural phenomena, for our own history and the history of the pre-Columbian inhabitants of the continent, for memorials of our national progress—offer the ideal places where, as part of the relaxation from the daily grind, millions of our people can find themselves.

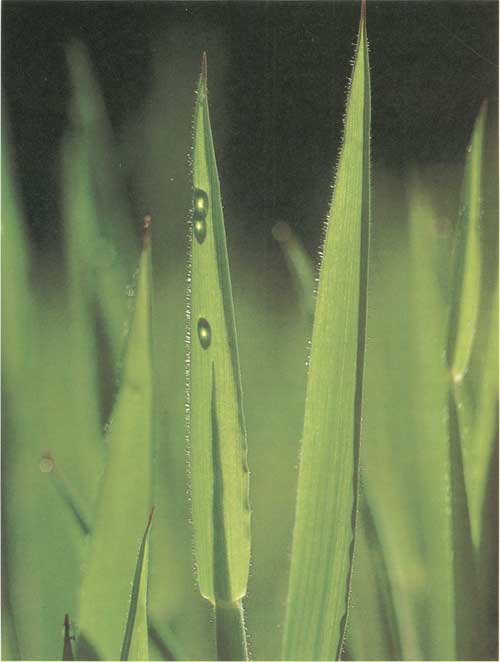

The illustrations on the following pages show the way millions of Americans—men, women, children, and, above all, family groups—use these priceless areas, not merely for the re-creation of their physical well-being but for the discovery of the delicate entity that make You You and Me Me.

Freeman Tilden

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tilden1/intro.htm

Last Updated: 12-Nov-2010