|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Who am I? Reflections on the Meaning Of Parks on the Occasion of The Nation's Bicentennial |

|

NATURAL AREAS

The national parks, and the scenic and scientific monuments, preserve for future generations of Americans, and for the world, those areas of transcendent beauty and wonder which we inherited. These are cultural treasures, as well as places for the refreshment of mind and spirit. They are the remaining "islands" in which life processes go on undisturbed, offering us the opportunity to understand a wilderness environment. In them one can observe the slow processes that have carved and shaped our earth and clothed it with plant and animal life. Without that comprehension, man cannot realize his own social life—so different, and yet with such vital correspondences!

|

Search for Continuity |

Dr. John C. Merriam, the famous paleontologist, was one of the fathers of interpretation in the National Park Service. With a group of other men of science, he laid the foundation in the '20s for the creation, in the national parks, of a communication network that has brought to visitors the truths that lie behind what the eye sees. No man was more effective, in his writings and lectures, in demonstrating the continuity—nature's flow from beginnings to present—in the billions of years since our planet came into being.

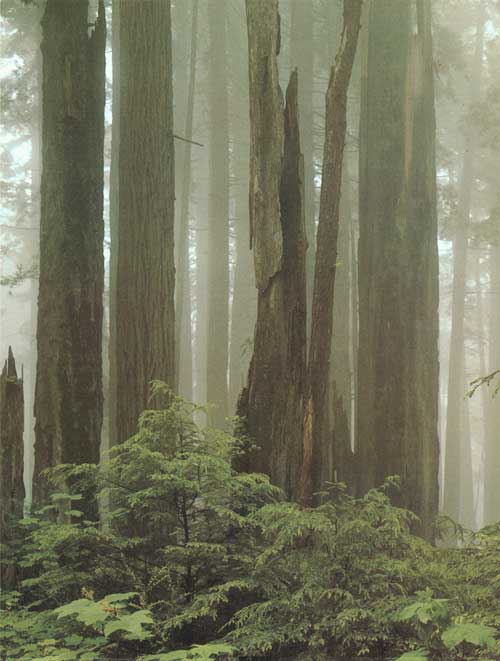

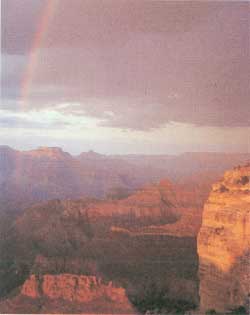

Merriam, sampling nature in Grand Canyon, at Yosemite, in the Redwoods, sought a continuity in human life that could be regarded as similar to that which he discovered in the organic and inorganic world. His last volume, printed before he died, was considered a bit on the emotional side by his tougher-minded scientific associates.

But it was a noble effort, and it demonstrated that Merriam himself had never failed to inquire, of himself, as he worked among fossil and living creatures, Who and what am I? Whence? How? By what causes am I the I that I am? A meaningful search, and it can be a consoling one.

| With the Eye of the Mind |

|

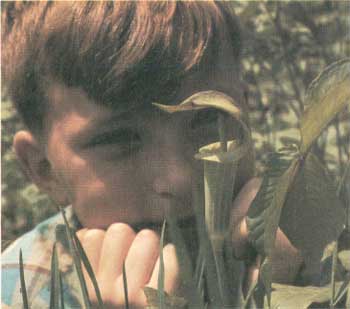

The child in the picture is looking at a wildflower in the Potomac River Valley. The child looks, examines, and enjoys the experience, but does not see. That seeing, we hope, will come later, as an adult. To quote Charles Darwin, the sight will then be with the "eye of the mind." Because, really to see, one must know how the flowering plant happens to be where it is; how it has adapted itself to the conditions where it grows; what is its relation to sun and shade; what life partners it has. There is a tiny flower in the great Redwood groves of California which over eons has been the companion of these forest giants. And in the subarctic conditions that prevail on the top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire, there is a flower that has its own particular butterfly, as consort. Whether you call it the study of ecology or the "awareness of environment," the National Park Service believes that part of its mission is to do all within its power to take the parks to the children, and the children to the parks, to begin the adventure of seeing with "the eye of the mind."

|

Stardust |

Noting that all the elements found in the universe, even the noble gases, are to be found here with and in us humans, a poetically minded scientist remarked that "we are stardust." It is a thrilling fact that thousands of years ago a Vedic eastern philosopher came to somewhat the same conclusion. "Tat Tvam asi," said the Sanskrit scroll: meaning "That are thou." Look around you: whatever your eyes meet, that is something of yourself. Inorganic and organic kinships alike. Transcendent as man is over other creatures, which have evolved from the first tiny forms that found how to flourish from the 20 percent of oxygen breathed into the atmosphere by plant-life, it is worth remembering that in dependence on this miracle of photosynthesis, we are one with the worm, the butterfly, the whale. As the key producers in the chain of life, plants alone have the power to take the sun's energy, and by combining it with air, water, and broken-down rock, produce a living tissue. We should bow to the trees and the grass when we come from the house in the morning. They are more important to us than a paved highway.

| A Matter of Words |

|

Environment. Ecology. These two words have abruptly come into the language of the dinner table and the commuter train. They are no longer the exclusive property of the natural scientist. Ecology. It is a coined word that was not in the Greek mind, though it is based, in part, on the Greek word "oikos," which meant "house." It signifies, now, the interrelationships and interdependence of the organic life within any habitat. Community, rather than individual, life. Life's chain, or web. But look at it another valid way. The good old English word "husbandry" meant the practice of ecological discernment and prudence by "the man of the house." As nature seeks equilibrium, though there is never perfect balance, so the husbandman seeks the wise balance in his "housekeeping." He puts back, instead of always taking out. For every debit, a credit. He does not regard nature as a slave, but as a generous silent partner. We can profitably consider that definition of ecology when we inquire as to who and what we are.

|

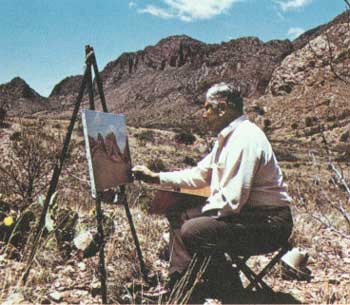

So He Sits at the Easel |

He sets up his easel on an outwash of the Chisos Mountains in Big Bend National Park, and paints what he feels. Maybe, when the picture is done, the art critic might say it wasn't very good. Well, what of it? He is not painting his feelings about nature to please the critic. Something of his very self is in the pigments that cover the canvas.

To some degree our artist in Texas has answered the question "Who am I." He finds that he cannot live by bread alone. Certainly he must have bread, or its equivalent. But there is beauty, too; and not just the beauty of scenery, or the beauty of the slanting sun that lights the walls of the Carmen Range. There is the beauty in the order of nature; of a certain justice in the natural world that forbids excess and encourages temperance. We like to think, too, that there is an essential good toward which we, among the myriad other forms of life, are moving. Not to be proved by calculus and microscope. But this painter of beauty in the desert responds to his belief. And, said Emerson, no matter what the exact testimony of belief may be, it is not as wonderful as the fact that man has the will to believe.

| As It Once Was |  |

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., inherited from his father a love of the serene out-of-doors. That he might view the noble scenery of forest and shore on Mount Desert Island in Maine in a leisurely way, he began to construct carriage roads. First these were for his personal use; but building them gave him a new and philanthropic idea. Why not give the roads to the Government, to become part of Acadia National Park? This he did, laying the foundation for yet another creative, cooperative partnership between private citizens and their Government so that future generations might know the quiet pleasures of a quality environment.

Thus, in Acadia, there are more than 50 miles of beautifully conceived roads on which mechanized vehicles cannot go, but which the hiker, the horseback rider, the buggy-driver, and the bicyclists can follow through some of the sweetest and most consoling landscape the eye of man has seen.

|

Who Will Give Up What? |

Here they are, husband and wife, far from suburbia and smog, backpacking in Rocky Mountain National Park. The air is crystalline. No trucks, no imitation of the Joneses. No slums, no violence, no furious pace of getting from nowhere in particular to the same place. A couple finding themselves. And, while they are hiking, though mostly they are silent, they do occasionally talk of home, where they have a nice house in the suburbs, with a plot of grass and, of course, a washer and a dryer in the basement.

"After all," he says to her, "this is fine—for a rejuvenating holiday. But if we are all Thoreaus, we'd have few comforts. Technology may have us down, but if we are on a retreat from the machine, somebody has to give up something that comes from the machine. What'll you give up, Kathryn?"

"Joe, I've been thinking about it. I don't really want to give up any of my gadgets. I'm used to the gadgets, and they're used to me. But it's obvious that we've strayed too far from an honest partnership with nature, and I'll pay my share of the price of getting clean."

Joe said nothing in reply. But he was thinking. And the back country of the Rockies is a place where you can really think.

| To Know |  |

To know, by seeing, the deciduous trees and the evergreens; to note the differences in leaf and form of the chestnut oaks from the red and white and pin and willow oaks, and of the hemlock and pine and spruce and fir; land-building and erosion; dunes, and rocks that were once wind-blown sands; and above all, the beauty of the landscape.

To know, by feeling, the barks of young and old birches and beeches and locusts and palms and madrones; and ferns and mosses and the thorned things of the desert.

To know, by odor, the clovers and the honeysuckles; and the pungency of the salt marsh, new cut grass and hay; the sulphur spring and the delicate scent of the wild strawberry.

To know, by taste, the resinous tang of the fir-balsam, the wintergreen flavor of the blackbirch twig; sassafras and sarsaparilla and many a root and herb.

To know, by hearing, the note or song of the warbler and the robin; the hoarse challenges of jay and raven; the cries of the sea birds and the laughter of the loon.

These, among a myriad of other experiences, should be the inheritance of children; and in the National Park System they can satisfy that precious need.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tilden1/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 12-Nov-2010