|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Who am I? Reflections on the Meaning Of Parks on the Occasion of The Nation's Bicentennial |

|

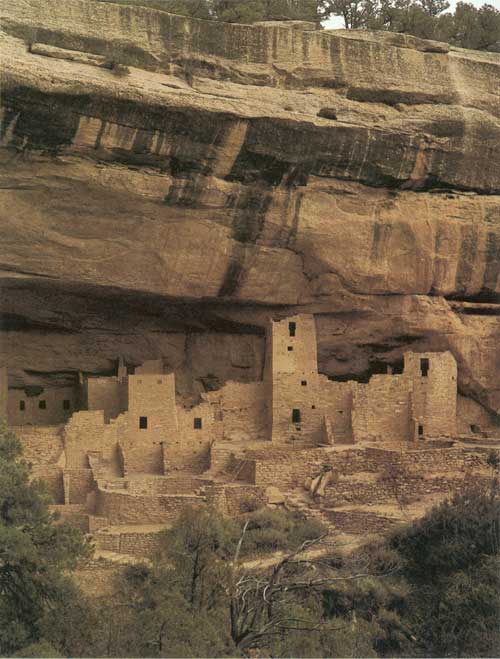

HISTORICAL AREAS

In the historical areas of the National Park System are preserved the epic pages of the national march. The prehistoric dwellings of a people who were on the continent long before Columbus came form a kind of preface to this volume. We tread the trails of the Spanish conquerors, the French fur trappers, the Oregon migrants. We come in actual touch with the sources of our greatness and prosperity. Here great deeds were done; heroic thoughts were transmitted; here great problems were grappled with and decisions made. Sometimes these areas are places of, or are surrounded by, great beauty; but the basic theme of these places is the will of man to throw off mental and physical shackles and to achieve.

|

Bread of the Ancients |

In the red-rock country of our Southwest there can be found a profusion of mortars and pestles with which the pre-Columbian Indians ground their seeds and maize. The mortar was a fragment of rock in which a basin had been found, or made. A pothole in the riverbed would do. The pestle, or mano, was a stone fashioned to fit the hand. This was infant technology, from which we have come a long way. We now remove the vitamins from cereals and then put them back.

There was one drawback to the Indian milling, the product was tough on the teeth. In the process of grinding, some of the particles of silica were bound to enter the meal, so there was a wearing-down similar to that which happens to aged ungulates. And no dentures.

The North American toolmaking man had rude implements: but he also had a feeling for beauty. There are stone axheads, for example, where the material was obviously chosen for its natural attractiveness, and then beautifully polished. How could polish make it more efficient: An ax is an ax, is it not? No; it can also be the personal expression of the budding aboriginal artist, who drew the sense of beauty from his environment and was accustomed to look for long hours at the moon and stars.

| The Tone of the Bell |

|

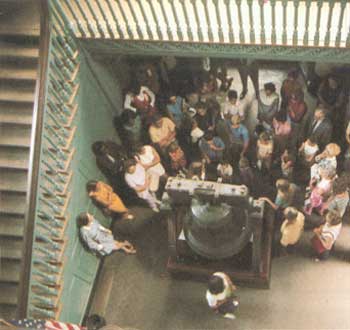

There are many bells, but for Americans there is only one Bell.

The colonial delegates who met in Carpenters' Hall in 1774, in the "City of Brotherly Love," were skilled in the study of political science. They had learned well the lesson from Montesquieu that "in constitutional states liberty is but a compensation for the heaviness of taxation; in despotic states the equivalent liberty is the lightness of taxation." The taxes levied upon the colonials by the British Crown were not really burdensome. But where a political voice in their own destiny was denied, even light taxes were unbearable. So the colonies, voting heavier taxes upon themselves, declared themselves free and independent.

The study of history is not a deterrent of mass error; that is plain. But from history we learn who and what we are, as individuals and as a nation. Not only at Independence Hall, but in all the National Park System's historical preserves, the thinking visitor is revealed to himself. He asks himself the questions: "What would I have done, under these circumstances? How would I have measured up to need and opportunity?"

The generations of school children who come to see and reverently to touch The Bell go home with that something which the schoolroom and the book can not impart.

|

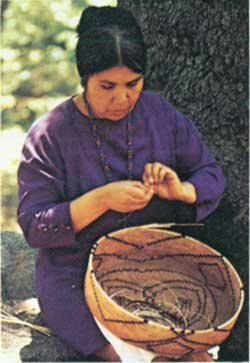

Julia Finds Her Niche |

Meet Julia Parker. Julia, an Indian girl who lives in Yosemite, was unhappy. One day, when talking with a friend, she mentioned her troubles. The Indian, she said, is losing what could be called his Indian-hood. The television and other "devices of the white man" were depicting Indians in a way that was demoralizing the younger folk. They were getting the wrong aspect on life. She felt at loose ends, herself. What could she do?

Could she weave baskets, her friend asked? No. She had never learned. "Isn't there one of the older women who could teach you?" Yes, she thought of one who could.

So Julia, gathering her fernroots and willow stems and redbud bark, weaves baskets. So far as she is concerned, she has a communication with nature. The Indian in North America exploited nature for his existence, but always with reverence. He knew who he was.

Sir Julian Huxley said that "Man must resume his unity with nature, while keeping his transcendency over nature." Yes; we do not want to revert to the cave, or even to the wax candle for reading. But as Julia knows, it must be a transcendency with reverence. Or it will be transcendency with disaster.

| What Does It Tell Me? |

|

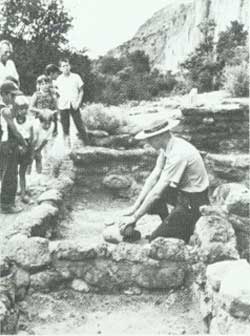

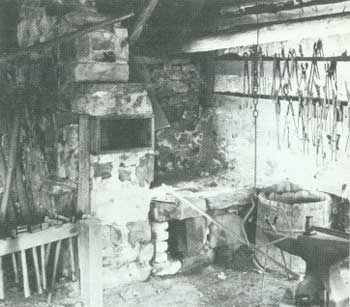

Emerson said: "The world exists for the education of each man. There is no age, or state of society, or mode of action in history, to which there is not something corresponding in his life." Thus, the visitor stands in the blacksmith shop at Hopewell Village, a national historic site, and sees himself as a part of that busy community life that went on in the latter part of the 18th century when the charcoal furnace of Mark Bird was smelting the nearby iron ores of southeastern Pennsylvania and casting the pigs into stoves and pots, kettles, and hammers, to supply a young but vigorously growing country. It was technology of a rude kind, compared with the prodigious machines of today, but it was nevertheless technology. Hopewell was a community that was almost wholly self sustaining. The thoughtful visitor, seeing these simple tools and devices, places himself back in those days. In his mind's eye he places himself as blacksmith, as miner, as woodcutter or teamster. There am I. Would I have been happy in that simple life? And what constitutes happiness? Is it the possession of much, or of the quality of existence. Questions like that. Finding one's self. Answering the question: "Who am I?"

|

Mule Power and Tranquility |

One of the delightful experiences for the visitor in the National Capital Parks is that journey on the barge that goes up the C&O Canal a few miles from Georgetown. It is a flashback to the day of slow motion, when people had time. Many a Washington and Virginia resident took the barge to go up the Potomac Valley to visit the folks. Going through the locks built of cut granite, you could reach out and pluck a spray of the mint that grew in the cracks of the walls. To make a julep, maybe. Technology! Fast moving mechanization! Hardly had the canal got on its financial feet—if it ever really did—when the steam locomotive made its appearance. The day that the first rail was laid, parallel to the canal, was the doom of this leisurely transportation, though the enterprise lingered for many years as a cheap way of moving certain kinds of freight. All the way to Cumberland the canal was dug. At Paw Paw the builders wondered whether to follow a big bend of the river, or tunnel under a mountain. They decided on a tunnel, and when you walk through the tunnel today you note that the wooden rail of the towpath is still slick to the hand where the boat-rope dragged along it. To visit the canal is to feel day before yesterday and to realize how far and fast you and the machine have come.

| The Drums of Conflict |

|

It was "our war"—that civil strife from '61 to '65; and the battlefields continue to draw a stream of visitors year after year: Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Antietam and Chancellorsville, and even those scenes that are seemingly less significant. Truly, there was no skirmish that did not play its role in the total drama. Pea Ridge, in Arkansas, for example. It was not a major battle, but it decided a major consideration: which way, Union or Confederate, Missouri would lean. The thoughtful visitor to the battlefield areas will have, besides his curiosity about weapons and strategy and tactics, sober reflections about the Civil War itself, and about the age-old moral problem of war. Many years ago Prof. William James, the great psychologist of Harvard, wrote a pamphlet entitled "The Moral Equivalent of War." James perceived that war brought out of combatants the best as well as the worst of human qualities: valor, self-sacrifice, compassion, magnanimity. He wondered whether there might not be, in peaceful social human relations, something that would equally summon up those noble attributes. Still, the search goes on...

|

Where Is the Villain? |

According to alarms being sounded, Man finds himself boxed in by his own fertility—both physical and intellectual. There seems to be too much of everything for our own survival. And it is natural, since we are not going to emerge from this crisis without penalties and discomfort, to seek the villain in the piece.

Technology—the civilizing instrument of toolmaking Man—has proceeded in a straight line from the exact scientist to the "ultimate consumer." All so perfectly natural, and to a certain point so laudable.

We don't want to reverse the trend of technology, go back to kerosene lamps and the slow, though excellent, grinding of the corn by the stones of Peirce Mill in Washington, D.C.'s Rock Creek Park. Where is the point of attack? Perhaps the comic-strip artist found the villain when he paraphrased the naval hero's words: "We have met the enemy and they are us."

| But it Flew! and Now . . . |

|

Whether it was an accident that the boy happened to be flying his kite on the massive sand dune near Cape Hatteras, or whether the photographer contrived the scene—what difference? It was felicitous.

The Wright Brothers Memorial marks the spot where human aviation, as now known, began. Their plane flew only a short distance; but it flew. And now you can be in Tokyo from Washington and in San Francisco from London in the time it took George Washington to get home to Mount Vernon when the roads were bad.

First, small airplanes. Then larger airplanes. Then giants of the sky that can carry hundreds of passengers and attain in the upper air a speed much above that of sound. It is an astounding example of the proficiency of scientific and technical Man.

It has drawbacks. The law of compensation seems naturally immutable. There is pollution, and there is a sonic boom to consider. Above populated areas, groundlings may not relish the shocks—nor will delicate instruments. Over the wilderness areas the wild creatures may enjoy it even less.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tilden1/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 12-Nov-2010