|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Who am I? Reflections on the Meaning Of Parks on the Occasion of The Nation's Bicentennial |

|

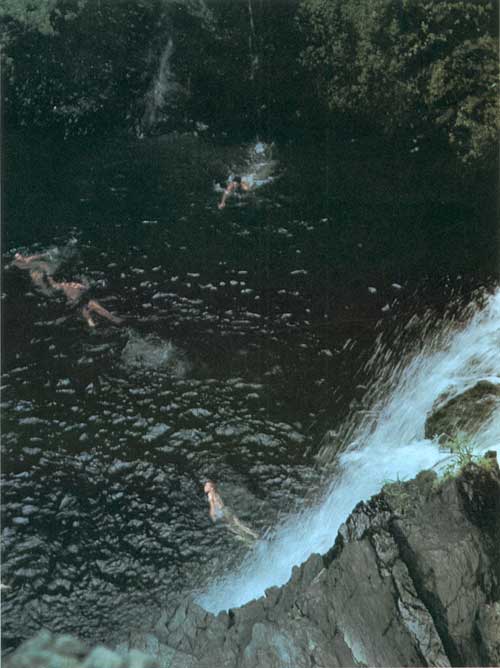

RECREATIONAL AREAS

Wholesome, restorative, and happy physical recreation is the primary purpose of the national seashores, the parkways, and the national recreation areas. Here one escapes from the drag of humdrum dailiness and indulges in the play-spirit, using the ocean beach, the impounded lake, the easy progress through ribbons of roadside natural beauty—all to gain mental and spiritual renewal. But of course all such areas have other values beyond those of simple recreation. There may be steep-walled canyons to explore by boat; there is always the strange life community that inhabits the seashore duneland, and if you wish to mingle a little adventure into the natural environment along with your holiday romping, the option is yours.

|

The Thing Itself |

It is much more than a century ago that Edward Hitchcock was President of Amherst College, in Massachusetts. It was a small college by today's standards, and the doctor was not merely the head, but also taught a class in geology. And, for the period, he was an outstanding geologist. It was he who studied the dinosaur tracks in the Connecticut Valley and started the scientific specialty of ichnology. But to his faculty, Hitchcock was eccentric and annoying. He made it a practice to take his students out into the field; to study the rocks and freshen their surfaces with a hammer; to collect specimens. Worse than that, he actually invited youths and maidens of the village to go a-trailing with his class. The faculty was appalled at this undignified, unprofessional conduct. It reflected on the college; it paled the luster of the teaching art. The students should be in the classroom, and learn from textbooks. Fortunately we have passed, long since, that kind of pedagogical nonsense. To know the natural world, to know one's self, is to go where things are: To begin in the primary grades of school to look, to listen, to touch, to taste, to smell. And, as adults, never to cease knowing nature by meeting her in person. That is the ideal of "interpretation" in the National Park Service.

| Be a Happy Amateur |

|

The lovely old word "amateur" has been sadly mishandled. To most persons the word now means bungler, a botcher, a producer of poor results. But the old meaning of the word was based upon the Latin word "to love," and it described a person who did things, or made things, not for the material gain involved, but for sheer love of it. Many of the great scientists of the Latin Renaissance in Europe were amateurs. They did not professionalize.

Fortunate are the men and women who, while they are earning their daily bread, commuting to the office or factory, and tied to the desk or machine, yet find time to go into the fields and woods and find their place in nature.

How could that lawyer in Denver, who knows more about the hummingbird than anyone else—how could he ever be bored? Or that Ohio woman—not a paid specialist—to whom you would go if you wished to know all about sparrows? Or a man in Arizona who can speedily flake an arrowpoint or a spearpoint as good as any aboriginal product? Such happy amateurs bored? Nonsense.

|

On a Glacial Boulder |

At the entrance gate of Indiana Dunes State Park there is a glacial boulder left by the continental ice sheet that departed from the northeastern part of our country not more, perhaps, than 12,000 years ago. Affixed to the rock is a plaque, with this verse:

All things by immortal power, near or far,

Hiddenly to each other linked are:

Thou canst not stir a flower

Without troubling of a star.

This quaint way of expression is by the poet Francis Thompson, who probably never in his life used the word "ecology." But this is the concept that the interpreters of the National Park Service try to enunciate to their visitors at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore and at other parks: the binding relationship of each fact of the cosmos to each other fact. Emerson's beautiful poem called "Each and All" is based upon the same idea of relationships.

Incidentally, this plaque, with its verse, was probably chosen for the entrance gate by Col. Richard Lieber, a philosopher in the world of parks whose humane impulses and generous imagination were so important in the early days of the State parks movement.

| The Way of Nature |

|

The couple is walking a restful lane that leads from the Blue Ridge Parkway in the southern Appalachians. There is time to stroll and time to make meaningful talk in this quiet haven. As interesting as the human adventure is the split rail fence that borders the trail. Rived out of chestnut, without a doubt.

There was a day in spring when this Appalachian forest was poseyed with the creamy white blossoms of the American chestnut as far as the eye could see. Then came a blight from abroad; and now this noble tree which provided the hill folks with rafters and shakes for their cottages, and food that was shared with the squirrels, is no more. Saplings still spring from some of the old roots, but the new trees succumb as juveniles.

It's all part of nature's incessant change. The niche that was occupied by the chestnut will be taken over. There seems to be a lesson here, for Man is becoming painfully aware that his niche is not invulnerable.

|

On the Strand |

There is something about man's delight in the seashore and the sandy beach that makes us think that primitive man came into his existence at the edge of the sea. Indeed, we get a curious and possibly significant suggestion about this from the most ancient Chinese language. The ideograph which means "mother" appears within the symbol which stands for "the sea." It cannot be accidental. What does it mean? Did those first Oriental writers share a quite modern biological theory that all life originated on the littoral? Or did they merely mean that Man got his food from the sea and used it for transportation—all that sort of practical mothering? The National Park Service now has some choice preserves on the seashore. Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras and Point Reyes and Padre Island offer experiences for the millions who flee from the smog and the daily humdrum to breathe salt air and bare the body to Father Sun. Little wonder that Rachel Carson and Ann Lindbergh have written of the soul-restoring qualities of the strand. These park areas, avowedly, are places where the primary use is physical recreation and relaxation. But there is much more in them for those who wish it. Back of the dunes or the cliffs, as the case may be, there is much to seek and find of the other forms of life with which our own is meshed.

| And . . . In Winter, Too |

|

There is a delightful use of some of our national parks that too few visitors know. Where climatic conditions make it possible, we can have an invigorating outing under the steely blue winter sky on a terrain that cannot be injured or "used up" by this kind of use. The cross country skier, the snowshoer, the skater, and even the horse-drawn sleigher (jingle bells!) have no greater impress on this landscape than the sand castles and forts so joyously erected on the beach by children. Sun and ocean wield mighty erasers.

Go into the northern woods, or the highland forest anywhere, and have a notable experience in winter. The quiet is unbroken except for the notes of a few birds. The jay will challenge you—even gladly insult you. If you are near a pond, listen. Thoreau used to hear the voice of Walden Pond when it was frozen deep.

You will find that, though you see no animal, you are really not alone. The rabbit has crossed here, and perhaps just ahead of a fox. But much of life that was so active last July is asleep under the virginal white blanket.

|

Leaven of Beauty |

They say, those who ought to know, that the world of Man has reached the moment of truth, as a result of our prodigious knowledge and our lack of wisdom. Is it not, at least in America, that we have made it so easy to exist that we have made it difficult to live?

This may be especially true in regard to our cities. The urban population is now far greater than the rural, and this ratio is likely to grow. And let nobody think that a city is merely an overgrown village, or that the difference is merely a matter of multiplication. The city has its own genius, and though it offers certain cultural advantages, it has a sharp fang of competition that easily breeds fear and unrest. Fouled air, noise, a lack of the soothing darkness of night, restrictions upon diversity of activity, the neurosis of hurry, slums and squalor—and above all, mere crowding, which in excess is not good for animals.

Dispersal? Back to the land? It is already suggested. A long, difficult, and costly task is ahead to relieve this sullen danger. But one thing can be done, while we await the engineering and social solution. We can introduce a touch of natural beauty into the city—plots of green oxygenating grass, flowers to create spots of gentleness. For every hovel that is razed, a group of trees should arise.

| For Those Who Come After |

|

The idea is found in many fields of ancient philosophy, but nowhere is it more charmingly expressed than in that amazing repository of doctrine and folklore, dialogue and commentary known as the Talmud.

"Chonyi the Magid once saw in his travels an old man planting a carob tree, and he asked him when he thought the tree would bear fruit. 'After seventy years,' was the reply. 'What?' said Chonyi. 'Dost thou expect to live seventy years and enjoy the fruit of thy labor?' Said the old man: 'I did not find the world desolate when I entered it, and as my fathers planted for me before I was born, so I plant for those that will come after me.'"

Have we forgotten? Not altogether. For we have preserved in our national parks, for our American posterity, vast areas of the natural beauty and wonders, the record of pre-Columbian peoples of the continent, and precious memorials of our own occupation and development of the land. But more is to be done. Let it not be said by those who come after us that in our march of material progress, we lost sight of the needs of the unborn, which may prove to be greater than our own.

More open spaces are needed. More serene havens of refuge for spiritual and moral re-creation. Not forgetting sun and forest and sand for the jaded body, either. We have done well; we can and must do better.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

tilden1/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 12-Nov-2010