|

YELLOWSTONE

"The place where Hell bubbled up" A History of the First National Park |

|

THE UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY

During the late 18th century those wandering heralds of civilization, the fur trappers, filtered into the upper Missouri country in search of a broad-tailed promise of fortune—the beaver. The early trappers and traders were mostly French Canadian, and the great tributary of the Missouri, the Yellowstone, first became known to white men by its French label, "Roche Jaune." None of the earliest trappers, however, seem to have observed the thermal activity in the area that would some day become a national park, although they probably learned of some of its wonders from their Indian acquaintances.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition passed just north of Yellowstone in 1806. Though Indians told them of the great lake, they remained unaware of the area's hot springs and geysers. While Lewis and Clark were exploring the Northwest, a trader appeared in St. Louis with an Indian map drawn on a buffalo hide. This rude sketch showed the region of the upper Yellowstone and indicated the presence of what appeared to be "a volcano . . . on Yellow Stone River." After his return to St. Louis, Clark interviewed an Indian who had been to the area and reported: "There is frequently heard a loud noise like Thunder, which makes the earth Tremble, they state that they seldom go there because their children cannot sleep—and Conceive it possessed of spirits, who were averse that men Should be near them." But civilized men were not yet wholly ready to believe "a savage delineation," preferring to with hold judgment until one of their own kind reported his observations.

|

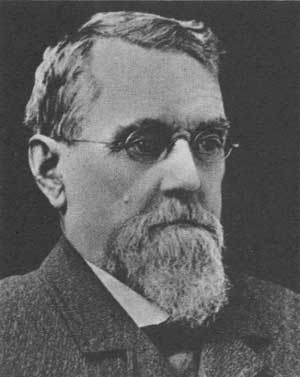

| Joseph L. Meek |

|

| Jim Bridger's tall tales popularized the wonders of Yellowstone, but made them unbelievable. |

In 1807 Manuel Lisa's Missouri Fur Trading Company constructed Fort Raymond at the confluence of the Bighorn and Yellowstone Rivers as a center for trading with the Indians. To attract clients, Lisa sent John Colter on a harrowing 500-mile journey through untracked Indian country. A veteran of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Colter was a man born "for hardy indurance of fatigue, privation and perils." Part of his route in 1807-8 is open to conjecture, but he is known to have skirted the northwest shore of Yellowstone Lake and crossed the Yellowstone River near Tower Falls, where he noted the presence of "Hot Spring Brimstone." Although a thermal area near present-day Cody, Wyo., later became famous among trappers as "Colter's Hell," Colter is more celebrated as the first white man known to have entered Yellowstone. The privations of a trapper's life and a narrow escape from the Blackfeet in 1808 prompted him to leave the mountains forever in 1810. But he was the pioneer, and for three decades a procession of beaver hunters followed in his footsteps.

Though most of the trappers who entered Yellowstone were Americans working for various companies or as free traders, some Canadians also visited the region in the early days. At least one party of Hudson's Bay Company men left a cache of beaver traps within the park. By 1824 Yellowstone seems to have been fairly well known to most trappers, judging by the casual note of one in his journal: "Saturday 24th—we crossed beyond the Boiling Fountains. The snow is knee deep." In 1827 a Philadelphia newspaper printed a letter from a trapper who described his experiences hunting furs and fighting Blackfeet in Yellowstone. This letter was the first published description of the region:

on the south borders of this lake is a number of hot and boiling springs some of water and others of most beautiful fine clay and resembles that of a mush pot and throws its particles to the immense height of from twenty to thirty feet in height. The clay is white and pink and water appear fathomless as it appears to be entirely hollow underneath. There is also a number of places where the pure sulphor is sent forth in abundance one of our men visited one of these whilst taking his recreation at an instan [sic] made his escape when an explosion took place resembling that of thunder. During our stay in that quarter I heard it every day. . . .

After 1826, American trappers apparently hunted within the future park every year. Joe Meek, one of the best known of the early beaver men, expressed the surprise of some of these early visitors: "behold! the whole country beyond was smoking with the vapor from boiling springs, and burning with gasses." Such reactions, however, gradually gave way to casual acceptance of the thermal activity.

Trappers had little for entertainment but talk; as a class they were the finest of storytellers. Verbal embellishment became a fine art as they related their experiences fighting Indians or visiting strange country. Perhaps the greatest of the yarn spinners was Jim Bridger. Though it is doubtful he told them all, tradition links his name with many of Yellowstone's tall tales.

In 1856 a Kansas City newspaper editor rejected as patent lies Bridger's lucid description of the Yellowstone wonders. Perhaps this sort of refusal to believe the truth about "the place where Hell bubbled up," as Bridger called Yellowstone, led him and other trappers to embellish their accounts with false detail. They related their visits to the petrified forest, carpeted with petrified grass, populated with petrified animals and containing even birds petrified in flight. They told of the shrinking qualities of Alum Creek, the banks of which were frequented by miniature animals. Fish caught in the cold water at the bottom of a curious spring were cooked passing through the hot water on top. Elk hunters bumped into a glass mountain. Such stories gave the features of Yellowstone the reputation of fantasies concocted by trappers. But the spread of this lore caused a few to wonder whether some fact might not lie behind the fancy.

By about 1840 the extirpation of the beaver and the popularity of the silk hat had combined to end the day of the trapper. For almost 20 years, Yellowstone, only rarely visited by white men, was left to the Indians. By the time of the Civil War, however, the relentless westward push of civilization and the burning memory of California gold drew to Yellowstone another herald of the frontier—the prospector. A rich strike was made in Montana in 1862, and the resultant stampede brought a horde of men to that territory. Despite often fatal discouragements from Indians, their lust for gold was such that they filtered into nearly every part of Yellowstone, but found not a sparkle of the magic metal. One enterprising gold seeker, a civil engineer and soldier of fortune named Walter W. deLacy, published in 1865 the first reasonably accurate map of the Yellowstone region. By the time the gold rush had died out in the late 1860's, the future national park had been thoroughly examined by prospectors. Although they were even greater liars than the mountain men, their tales of the wondrous land they had seen planted a seed of curiosity in Montana that was to impel others to take a careful look for themselves.

|

| Walter W. deLacy |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

clary/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2009