|

YELLOWSTONE

"The place where Hell bubbled up" A History of the First National Park |

|

THE COUNTRY DISCOVERED

Although Yellowstone had been thoroughly tracked by trappers and miners, in the view of the Nation at large it was really "discovered" when penetrated by formal expeditions originating in the settlements of an expanding America.

The first organized attempt to explore Yellowstone came in 1860. Capt. William F. Raynolds, a discerning Army engineer guided by Jim Bridger, led a military expedition that accomplished much but failed to penetrate the future park because of faulty scheduling and early snow. The Civil War preoccupied the Government during the next few years. During the late 1860's, however, stories of the area's wonders so excited many of Montana's leading citizens and officials that several explorations were planned. But none actually got underway.

Indian trouble and lack of a military escort caused the abandonment of the last such expedition in the summer of 1869. Determined that they would not be deprived of a look at the wondrous region, three members of that would-be venture—David B. Folsom, Charles W. Cook, and William Peterson—decided to make the trek anyway. Folsom and Cook brought with them a sensitivity to nature endowed by a Quaker up??bringing, while Peterson displayed the hardy spirit that came from years as a seafarer. All three, furthermore, had become experienced frontiersmen while prospecting for Montana gold. They acquired a store of provisions, armed themselves well, then set out on an enterprise about which they were warned by a friend: "It's the next thing to suicide."

|

| David E. Folsom |

|

| Charles W. Cook, 1869 |

That caution could not have been more wrong, for their journey took them into a natural wonderland where they met few Indians. From Bozeman, they traveled down the divide between the Gallatin and Yellowstone Rivers, eventually crossing to the Yellowstone and ascending that stream into the present park by way of Yankee Jim Canyon. They observed Tower Fall and nearby thermal features and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone—"this masterpiece of nature's handiwork"—then continued past the Mud Volcano to Yellowstone Lake. They pushed east to Mary Bay, then backtracked across the north shore to West Thumb. On their way home the explorers visited Shoshone Lake and the Lower and Midway Geyser Basins. The Folsom-Cook-Peterson exploration produced an updated version of DeLacy's 1865 map, an article in the Western Monthly magazine in Chicago, and a fever of excitement among some of Montana's leading citizens, who promptly determined to see for themselves the truth of the party's tales of "the beautiful places we had found fashioned by the practised hand of nature, that man had not desecrated."

By August 1870 a second expedition had been organized. Rumors of Indian trouble reduced the original 20 members to less than half that number. Among them were prominent government officials and financial leaders of Montana Territory, led by Surveyor-General Henry D. Washburn, politician and business promoter Nathaniel P. Langford, and Cornelius Hedges, a lawyer. Obtaining from Fort Ellis a military escort under an experienced soldier, Lt. Gustavus C. Doane, the explorers traced the general route of the 1869 party. They followed the river to the lake, passed around the eastern and southern sides, inspected the Upper, Midway, and Lower Geyser Basins, and paused at Madison Junction—the confluence of the Gibbon and Firehole Rivers—before returning to Montana. It was at this campsite that they, like their predecessors the year before, discussed their hopes that Yellowstone might be saved from exploitation.

|

| William Peterson |

Some of the members of the 1870 expedition lacked extensive experience as frontiersmen, and their wilderness education came hard. At times they went hungry because, according to Doane, "our party kept up such a rackett of yelling and firing as to drive off all game for miles ahead of us." One of their number, Truman Everts, separated himself from the rest of the party and, unable to subsist in a bounteous land, nearly starved to death before he was rescued 37 days later. But these problems were understandable. By the end of the expedition they had demonstrated their backwoods ability. The party had climbed several peaks, made numerous side trips, descended into the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and attempted measurements and analyses of several of the prominent natural features. They had shown that ordinary men, as well as hardened frontiersmen, could venture into the wilderness of Yellowstone.

Far more important, however, was their enchantment and wonder at what they had seen and their success in publicizing these feelings. As Hedges later recalled, "I think a more confirmed set of sceptics never went out into the wilderness than those who composed our party, and never was a party more completely surprised and captivated with the wonders of nature." Their reports stirred intense interest in Montana and attracted national attention. Members of the expedition wrote articles for several newspapers and Scribner's Monthly magazine. Langford made a speaking tour in the East. Doane's official report was accepted and printed by the Congress. All this publicity resulted in a congressional appropriation for an official exploration of Yellowstone—the Hayden Expedition.

|

| Henry D. Washburn, 1896 |

|

| Lt. Gustavus C. Doane |

|

| Cornelius Hedges |

|

| Truman C. Everts |

|

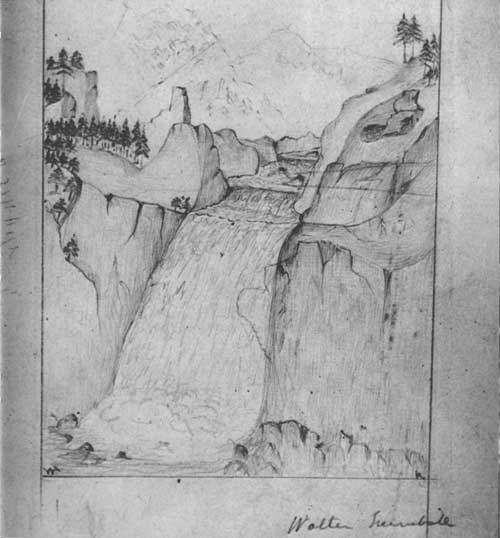

| Walter Trumbull's sketch of the Upper Falls of the Yellowstone, made on the 1870 expedition. |

|

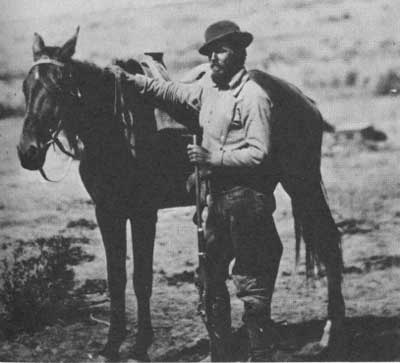

| The Hayden Expedition of 1871 on their way into the heart of the Yellowstone country. |

|

| "Annie," the first boat on Yellowstone Lake, was built and launched during the 1871 expedition. |

|

| Hunters with the 1871 expedition bring in a day's kill. |

|

| Jackson's self-portrait. He was the official photographer for both the 1871 and 1872 expeditions. |

|

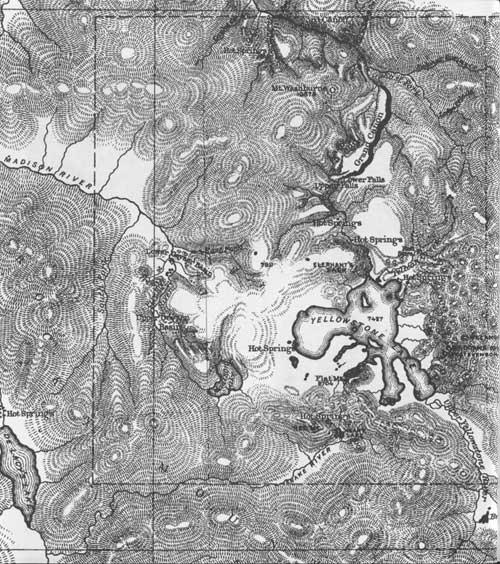

| After the 1871 expedition, Hayden published this map of the Yellowstone region. |

|

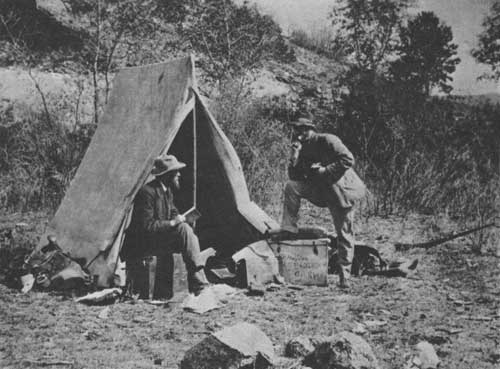

| Ferdinand V. Hayden (left), who led the 1871 expedition of Yellowstone, talks with his assistant Walter Paris. |

Ferdinand V. Hayden, physician turned geol ogist, energetic explorer and accomplished nat uralist, head of the U.S. Geological Survey of the Territories, had been with Raynolds in 1860. The failure of that expedition to penetrate Yellowstone had stimulated his desire to investigate the re gion. Aside from being a leading scientific investi gator of the wilderness, he was an influential publicist of the scientific wonders, scenic beauty, and economic potential of the American West. He saw the interest stirred by the Washburn- Langford-Doane Expedition as an opportunity to reveal Yellowstone in an orderly and scientific manner. Drawing on the support of the railroad interests—always proponents of Western explora tion and development—and favorable public reaction to the reports of the 1870 expedition, Hayden secured an appropriation for a scientific survey of Yellowstone. This expedition was supplemented by a simultaneous survey by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The dual exploration in the late summer of 1871 was more thorough than that of 1870, and it brought back scientific corroboration of earlier tales of thermal activity. Although a lot of the material vanished in the Chicago fire of 1871, the expedition gave the world a much improved map of Yellowstone and, in the excellent photo graphs by William Henry Jackson and the artistry of Henry W. Elliott and Thomas Moran, visual proof of Yellowstone's unique curiosities. The expedition's reports excited the scientific commu nity and aroused intense national interest in this previously mysterious region.

Members of all three expeditions from 1869 to 1871 were overwhelmed by what they had seen. The singular features of the area evoked similar reactions in all the explorers. This was the day of the "robber barons" and of rapacious exploita tion of the public domain. It was also a time of dynamic national expansion, when the Nation conceived its mission to be the taming and peopling of the wilderness. But most of the re gion's explorers sensed that division and exploita tion, through homesteading or other development, were not proper for Yellowstone. Its natural curi osities impressed them as being so valuable that the area should be reserved for all to see. Their crowning achievement was that they persuaded others to their view and helped to save Yellowstone from private development.

Hayden, assisted by members of the Washburn party and other interested persons, promoted a park bill in Washington in late 1871 and early 1872. Working earnestly, the sponsors drew upon the precedent of the Yosemite Act of 1864, which reserved Yosemite Valley from settlement and en trusted it to the care of the State of California, and the persuasive magic of Jackson's photo graphs, Moran's paintings, and Elliott's sketches. To permanently close to settlement such an ex panse of the public domain would be a departure from the established policy of transferring public lands to private ownership. But the proposed park encompassing the wonders of Yellowstone had caught the imagination of both the public and the Congress. After some discussion but surpris ingly little opposition, the measure passed both houses of Congress, and on March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed it into law. Yellowstone would be forever preserved from private greed and "dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people." The world's first national park was born.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

clary/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2009