|

YELLOWSTONE

"The place where Hell bubbled up" A History of the First National Park |

|

"THE WILD ROMANTIC SCENERY"

There is something about Yellowstone that has frequently brought out the poet, or would-be poet, in its visitors. Men who ordinarily would not bother to remark on their surroundings have in Yellowstone felt compelled to draft prose about the wonders they saw around them. This impulse was particularly keen in those who saw Yellow stone before the advance of civilization.

Little is known of the Indians' regard for Yellowstone's natural features during the thou sands of years they lived there. They did not leave their impressions in written form for the reflection of later generations.

But the fur trappers did. Several of them kept journals or related their experiences in letters and reminiscences. They used their observations to spin entertaining yarns, and they sometimes compared the surrounding beauty with what they knew back home. Yet they generally resisted the "womanly emotions" of praising scenery, and most of them were reluctant to reflect on nature's charms. A Maine farm boy named Osborne Russell, who went West in the 1830's to trap, chided his companions for their insensitivity:

My comrades were men who never troubled themselves about vain and frivolous notions as they called them; with them every country was pretty when there was weather and as to beauty of nature or arts, it was all a "humbug" as one of them . . . often expressed it.

What Russell saw in Yellowstone affected him deeply. He had reverent memories of one place in particular, a "Secluded Valley," located on the Lamar River near the mouth of Soda Butte Creek.

There is something in the wild romantic scenery of this valley which I cannot. . . describe; but the impressions made upon my mind while gazing from a high eminence on the surrounding landscape one evening as the sun was gently gliding behind the western mountain and casting its gigantic shadows across the vale were such as time can never efface from my memory . . . for my own part I almost wished I could spend the remainder of my days in a place like this where happiness and contentment seemed to reign in wild romantic splendor.

Thermal features drew the most frequent notice from Yellowstone's early visitors. Nathaniel Langford summarized the mystery and disbelief many people feel while observing them:

General Washburn and I again visited the mud vulcano [sic] to-day. I especially desired to see it again for the one especial purpose, among others of a general nature, of assuring myself that the notes made in my diary a few days ago are not exaggerated. No! they are not! The sensations inspired in me to-day, on again witnessing its convulsions . . . were those of mingled dread and wonder. At war with all former experience it was so novel, so unnat urally natural, that I feel while now writing and thinking of it, as if my own senses might have deceived me with a mere figment of the imagination.

But more often the hot springs, mud pots, fumaroles, and geysers seemed to suppress the poet and draw forth instead the amateur scientist. Most early accounts centered on attempts at measurement or analysis, or on speculations about the mechanisms of such features. For many of these novice geologists, the surprises at Yellow stone did not always come in the form of geysers or boiling springs. A. Bart Henderson, a pros pector, was walking down the Yellowstone River in 1867, near the Upper Falls, when he was

very much surprised to see the water disappear from sight. I walked out on a rock & made two steps at the same time, one forward, the other backward, for I had unawares as it were, looked into the depth or bowels of the earth, into which the Yellow [stone] plunged as if to cool the infernal region that lay under all this wonderful country of lava & boiling springs. The water fell several feet, struck a reef of rock that projected further than the main rock above. This reef caused the water to fall the remainder of the way in spray.

Henderson recovered his analytical composure and concluded, "We judged the falls to be 80 or 90 feet high, perhaps higher."

|

| Henry Elliott's sketch of the Lower Geyser Basin was part of the persuasive evidence produced by the Hayden survey. |

|

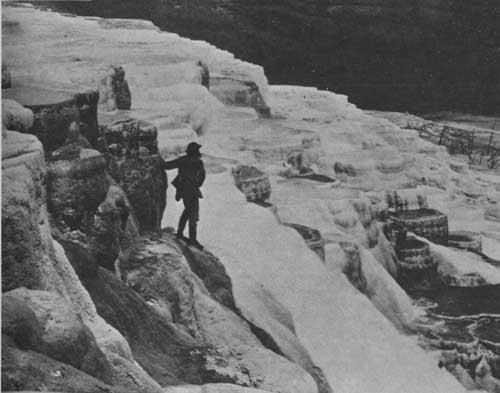

| Artist Thomas Moran, climbing on Mammoth Hot Springs, 1871. |

|

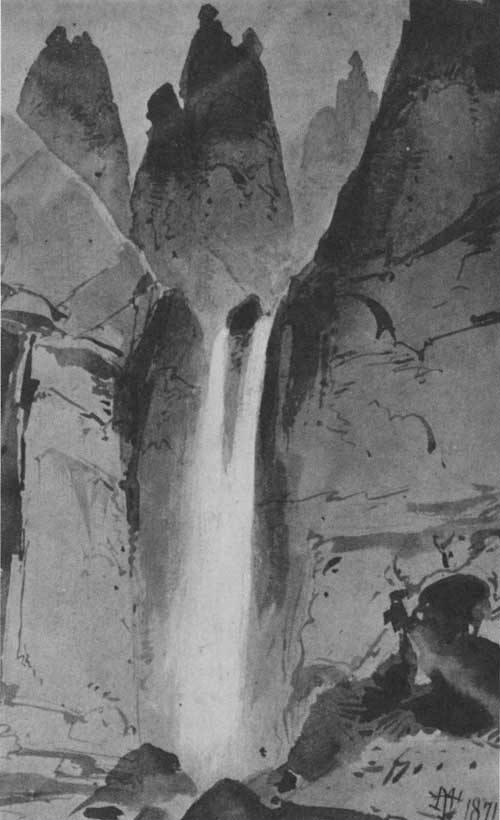

| Thomas Moran's field sketches of Tower Fall (top) and the hot springs at Mammoth. |

Because wildlife was plentiful everywhere in the West in the 19th century, the abundant wildlife of Yellowstone seldom drew the attention of early visitors, except when they referred to hunting the "wild game." Occasionally a diary registered that some physical feature had been endowed with the name of an animal. Prospector John C. Davis shot at what he thought was a flock of flying geese in 1864. But after a difficult swim to retrieve his prey, he decided that it was too strange to eat, and hung it in a tree. From that small incident Pelican Creek acquired its name.

Sometimes the wildlife forced their attentions on visitors. Henderson prospected in Yellowstone again in 1870. He christened Buffalo Flat because "we found thousands of buffalo quietly grazing." But the animals were evidently not flattered, for one night, "Buffalo bull run thro the tent, while all hands were in bed." As Henderson's party continued their journey, another bull attacked their horses, nearly destroying their supplies. Sometime later, the group "met an old she bear & three cubs. After a severe fight killed the whole outfit, while a short distance further on we was attacked by an old boar bear. We soon killed him. He proved to be the largest ever killed in the mountains, weighing 960 pounds." Two days later, Henderson "was chased by an old she bear . . . . Climbe[d] a tree & killed her under the tree."

But few encounters with wildlife were so unpleasant. Most travelers recognized that the animals of Yellowstone were an integral part of the environment. To David Folsom the voices of the animals were but the voice of nature, reminding men of their smallness in the natural world and of their aloneness in a strange country:

the wolf scents us afar and the mournful cadence of his howl adds to our sense of solitude. The roar of the mountain lion awakens the sleeping echoes of the adjacent cliffs and we hear the elk whistling in every direction . . . . Even the horses . . . stop grazing and raise their heads to listen, and then hover around our campfire as if their safety lay in our companionship.

The explorers of 1869, 1870, and 1871, writing for a wide audience, did their best to remain detached and to describe objectively what they had seen. But their prose sometimes became impassioned. Even the thermal features evoked poetic word pictures. Charles Cook was startled by his first view of Great Fountain Geyser:

Our attention was at once attracted by water and steam escaping, or being thrown up from an opening. . . . Soon this geyser was in full play. The setting sun shining into the spray and steam drifting toward the mountains, gave it the appearance of burnished gold, a wonderful sight. We could not contain our enthusiasm; with one accord we all took off our hats and yelled with all our might.

|

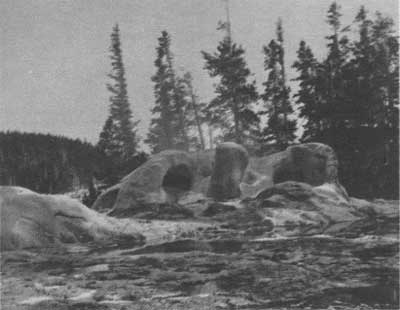

| Two early explorers examine Lone Star Geyser. |

|

| W. H. Jackson's photographs of Grotto Geyser (top) and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (bottom) were among the evidence that prompted Congress to establish the national park. |

Folsom recalled his last look at Yellowstone Lake this way:

nestled among the forest-crowned hills which bounded our vision, lay this inland sea, its crystal waves dancing and sparkling in the sunlight as if laughing with joy for their wild freedom. It is a scene of transcendent beauty which has been viewed by few white men, and we felt glad to have looked upon it before its primeval solitude should be broken by the crowds of pleasure seekers which at no distant day will throng its shores.

Even the scientifically minded professional soldier, Gustavus Doane, departed from an objective recital to exclaim that the view from Mount Washburn was really "beyond all adequate description." Speaking of Tower Falls, Doane became cautiously lyrical:

Nothing can be more chastely beautiful than this lovely cascade, hidden away in the dim light of overshadowing rocks and woods, its very voice hushed to a low murmur unheard at the distance of a few hundred yards. Thousands might pass by within a half mile and not dream of its existence, but once seen, it passes to the list of most pleasant memories.

The lieutenant dropped his reserve altogether when he sang the praises of the Upper and Lower Falls in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone:

Both these cataracts deserve to be ranked among the great waterfalls of the continent. No adequate standard of comparison between such objects, either in beauty or grandeur, can well be obtained. Every great cascade has a language and an idea peculiarly its own, embodied, as it were, in the flow of its waters . . . . So the Upper Falls of the Yellowstone may be said to embody the idea of "Momentum," and the Lower Fall of "Gravitation." In scenic beauty the upper cataract far excels the lower; it has life, animation, while the lower one simply follows its channel; both however are eclipsed as it were by the singular wonders of the mighty cañon below.

The Hayden expeditions of 1871 and 1872 were scientific ventures, composed of men of critical disposition who were prepared to take a circumspect, unromantic view of all they encountered in their path. Yet even they were moved to comment on the beauty of Yellowstone. Henry Gannett, one of Hayden's later associates, wrote:

In one essential respect the scenery of the Yellowstone Park differs from that of nearly all other parts of the Cordilleras, in possessing the element of beauty, in presenting to the eye rounded forms, and soft, bright, gay coloring.

Nor could the scholarly Hayden completely restrict himself to scientific explanations of Yellowstone's charms. Mammoth Hot Springs, he thought, "alone surpassed all the descriptions which had been given by former travelers." When he came to the Grand Canyon and the falls, he confessed that mere description was inadequate, that "it is only through the eye that the mind can gather anything like an adequate conception of them:

no language can do justice to the wonderful grandeur and beauty of the cañon below the Lower Falls; the very nearly vertical walls, slightly sloping down to the water's edge on either side, so that from the summit the river appears like a thread of silver foaming over its rocky bottom, the variegated colors of the sides, yellow, red, brown, white, all intermixed and shading into each other; the Gothic columns of every form standing out from the sides of the walls with greater variety and more striking colors than ever adorned a work of human art. The margins of the cañon on either side are beautifully fringed with pines. In some places the walls of the cañon are composed of massive basalt, so separated by the jointage as to look like irregular mason-work going to decay . . . .

Standing near the margin of the Lower Falls, and looking down the cañon, which looks like an immense chasm or cleft in the basalt, with its sides 1,200 to 1,500 feet high, and decorated with the most brilliant colors that the human eye ever saw, with the rocks weathered into an almost unlimited variety of forms, with here and there a pine sending its roots into the clefts on the sides as if struggling with a sort of uncertain success to maintain an existence—the whole presents a picture that it would be difficult to surpass in nature. Mr. Thomas Moran, a celebrated artist, and noted for his skill as a colorist, exclaimed with a kind of regretful enthusiasm that these beautiful tints were beyond the reach of human art.

Nathaniel P. Langford, first superintendent of the park, 1872.

Such were the men, from fur trappers to geologists, who preceded the civilized world into Yellowstone, and such were the feelings that nature produced in them. It was upon a stage thus set that Yellowstone entered into its greatest period—that of a wilderness preserved.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

clary/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2009