|

YELLOWSTONE

"The place where Hell bubbled up" A History of the First National Park |

|

"TO CONSERVE THE SCENERY AND THE OBJECTS THEREIN"

The Yellowstone Park Act was essentially directed at preventing private exploitation; it contained few positive measures for administering the preserve. The park's promoters envisioned that it would exist at no expense to the Government. The costs of maintenance and administration were to be borne by fees charged concessioners, who would provide the facilities that the public needed. For a long time, therefore, Yellowstone enjoyed little protection from pillagers. It took almost half a century of trial and error to develop a practical approach to administration and to discover what a "national park" should be.

|

| Nathaniel P. Langfod, first superintendent of the park, 1872. |

|

| Philetus W. Norris, energetic pioneer, perpetual showman, and second superintendent of the park. |

|

| Harry Yount, the park's first "gamekeeper." |

One of the first needs was more thorough exploration. During the more than two decades following its establishment, a number of expeditions traversed much of the park and added greatly to the general store of knowledge. Especially notable were the elaborate Hayden Expedition of 1872 and a series of military explorations of the park later in the same decade. In 1883 an impressive bevy of scientists and celebrities escorted President Chester A. Arthur during what was more a pleasure trip than an exploration. By the early 1890's the park was well mapped, most of its features had been recorded, and it had even been penetrated during the bitter winters.

But the emerging park soon faced a new set of problems. Squatters had already moved in, and vandals and poachers preyed on its natural wealth. No congressional appropriation provided for protection or administration.

The Secretary of the Interior did, however, appoint a superintendent. In May 1872 this honor fell to Nathaniel P. Langford, member of the Washburn Expedition and advocate of the Yellowstone Park Act. Receiving no salary, he had to earn his living elsewhere and entered the park only twice during his 5 years in office, once in the train of the 1872 Hayden Expedition and again in 1874 to evict a particularly egregious squatter. When he was there, his task was made more difficult by the lack of statutory protection for wildlife and other natural features.

Because there were no appropriations for administration or improved access, the park remained inaccessible to all but the hardiest travelers. Some of the visitors who did make their way to the neglected paradise displayed a marked propensity to go about, according to an observer, "with shovel and axe, chopping and hacking and prying up great pieces of the most ornamental work they could find." In 1874 a Montana newspaper queried: "What has the Government done to render this national elephant approachable and attractive since its adoption as one of the nation's pets? Nothing." Langford complained, "Our Government, having adopted it, should foster it and render it accessible to the people of all lands, who in future time will come in crowds to visit it."

|

| Early abuse of Yellowstone's wildlife. The elk in the photograph (bottom) were brought down to help feed the 1871 Hayden Expedition. Thirty years later buffalo were confined (top) near Mammoth so that visitors could see them with little effort. |

|

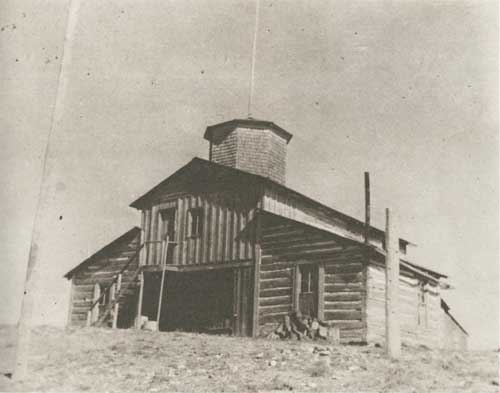

| The blockhouse, long called Old Fort Yellowstone, built by Superintendent Norris at Mammoth for park headquarters. |

|

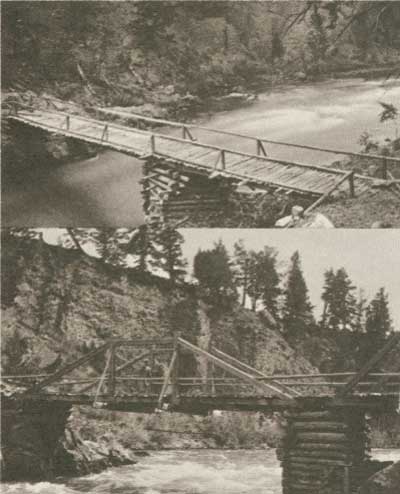

| Jack Baronett foresaw the attraction the region would hold for others, and in 1871 he built the first bridge aross the Yellowstone to capitalize on traffic into the area. These photographs show (top) the original bridge buil in 1871, and (below) the Army's reconstruction after the Nez Perce had destroyed first bridge. |

Political pressure stemming partly from accusations of neglect of duty forced Langford's removal from the superintendency in April 1877. He was replaced by Philetus W. Norris, a hyper-energetic pioneer of quite a different stamp. Shortly after taking office, Norris became the regular recipient of an annual salary and appropriations "to protect, preserve, and improve the Park." Bringing skill and industry to the task, he constructed numerous physical improvements, built a monumental "blockhouse" on Capitol Hill at Mammoth Hot Springs for use as park headquarters, hired the first "gamekeeper" (Harry Yount, an experienced frontiersman), and waged a difficult campaign against poachers and vandals. Much of the primitive road system he laid out still endures as part of the Grand Loop. Through ceaseless exploration and identification of the physical features, Norris added immensely to the geographical knowledge of the park. In this effort he left a prominent legacy, for among the names he liberally bestowed on the landscape, his own appeared frequently. One visitor felt he was "simply paying a visit to 'Norris' Park." Another caustically suggested:

Take the Norris wagon road and follow down the Norris fork of the Firehole River to the Norris Canyon of the Norris Obsidian Mountain; then go on to Mount Norris, on the summit of which you find . . . the Norris Blowout, and at its northerly base the Norris Basin and Park. Further on you will come to the Norris Geyser plateau, and must not fail to see Geyser Norris.

Despite the physical improvements he made in the park and his contributions to scientific knowledge, Norris fell victim to political machinations and was removed from his post in February 1882. As the ax fell, a Montana newspaper lamented:

We are led to infer that Peterfunk Windy Norris' cake is dough; in other words he has gone where the woodbine twineth; or, to speak plainly, he has received the grand bounce. It is extremely sad . . . We shall never look upon [his] like again.

|

| Capt. Hiram M. Chittenden, 1900. |

|

| Off-duty soldiers pass the time at the Canyon Soldier Station, 1906. |

|

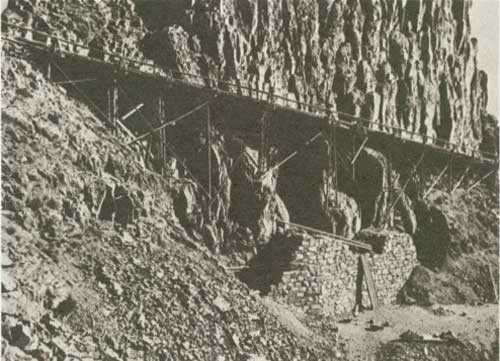

| The first bridge at the Golden Gate, built by the Army in 1884. |

|

| While the Army administered Yellowstone, visitors were treated every day to the spectacle of troops on parade. This platoon is drilling at Fort Yellowstone. |

|

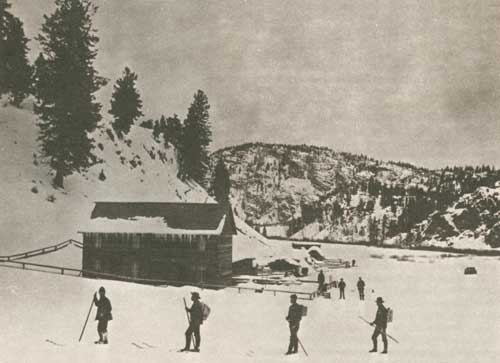

| An Army ski patrol sets out from Yancey's cabin. |

The removal of Norris was indicative of Yellowstone's plight. During its formative years, the park was fought over by interests that for political or financial reasons hoped to claim it as a prize and control it totally. Without legal protection against such exploitation or against poaching and vandalism, the park suffered greatly during its first two decades. An active and conscientious, if abrasive, superintendent like Norris was unable to fully protect the park. After his dismissal, promoters of schemes to build railroads and toll roads in the park and to monopolize accommodations usually blocked the appointment of capable superintendents and harassed any who showed signs of honestly striving for the benefit of the park. A succession of powerless and mediocre superintendents took office. Of one of them it was remarked:

It need only be said that his administration was throughout characterized by a weakness and inefficiency which brought the Park to the lowest ebb of its fortunes, and drew forth the severe condemnation of visitors and public officials alike.

It should be pointed out, however, that the national park was a totally new invention. No one had experience in the administration of such a preserve, and a long period of trial and error was bound to follow its establishment. The legal responsibilities of the Government were not fully recognized, for it was commonly believed that the public could best be served and the park best be protected by concessioners. Yet it was difficult to distinguish the honest concessioner from the exploiter, to determine what kind of legal protection would best serve the common good, and to identify those human activities detrimental to the park. The isolation of Yellowstone compounded these handicaps. Although some visitors were destructive and a few rapacious exploiters wielded enormous influence, the Government was honestly striving to find the proper course in a new enterprise. Fortunately, most early visitors restricted their activities to the peaceful enjoyment of Yellowstone's wonders.

Attempts were made in the early 1880's to bring law and order to Yellowstone. A body of 10 assistant superintendents was created to act as a police force. Described by some observers as "notoriously inefficient if not positively corrupt" and scorned as "rabbit catchers" by Montana newspapers, they failed to check the rising tide of destruction and the slaughter of game. For 2 years the laws of Wyoming Territory were extended into the park, but the practice of enforcement that allowed "informers" and magistrates to split the fines degraded the hoped-for protection almost to the level of extortion. After the repeal of the act authorizing such "protection" was announced in March 1886, the obviously defenseless park attracted a new plague of poachers, squatters, woodcutters, vandals, and firebugs.

The inability of the superintendents to protect the park appeared to be a failure to perform their duty, and in 1886 Congress refused to appropriate money for such ineffective administration. Since no superintendent was willing to serve without pay, Yellowstone now lacked even the pretense of protection.

|

| Horace M. Albright, 1922. |

|

| One of the first naturalists at Yellowstone, 1929. |

This circumstance proved fortunate, for the Secretary of the Interior, under authority previously given by the Congress, called on the Secretary of War for assistance. After August 20, 1886, Yellowstone came under the care of men not obliged to clamor for the job, and whose careers depended on performance—soldiers of the U.S. Army.

Military administration greatly benefited Yellowstone. Regulations were revised and conspicuously posted around the park, and patrols enforced them constantly. For the protection of visitors, as well as park features, detachments guarded the major attractions. No law spelled out offenses, but the Army handled problems effectively by evicting troublemakers and for bidding their return. Cavalry, better suited than infantry to patrol its vastness, usually guarded the park.

When appropriations for improvements increased, the Corps of Engineers lent its talents to converting the primitive road network into a system of roads and trails that in basic outline still endures. The soldier who left the greatest mark on Yellowstone was one of the engineers, Hiram M. Chittenden. He not only supervised much of its development and constructed the great arch at the northern entrance, but also wrote the first history of the park.

Army headquarters was at Mammoth Hot Springs, first in Camp Sheridan and after the 1890's in Fort Yellowstone, which still houses the park headquarters. A scattering of "soldier stations" around the park served as subposts. One survives today at Norris.

The most persistent menace to the park came from poachers. Although these intruders never killed any defender of the park—there was only one shoot-out with poachers in more than 30 years—their ceaseless attempts to make petty gains from the wildlife threatened to exterminate some animals. In 1894, soldiers arrested a man named Ed Howell for slaughtering bison and took him to Mammoth. The presence there of Emerson Hough, a prominent journalist, helped to generate national interest it in the problem. Within 2 months Congress had acted, and the National Park Protective Act (Lacey Act) became law, finally providing teeth for the protection of Yellowstone's treasures. Howell entered the park later that year to continue his bloody pastime. Appropriately, he became the first person arrested and punished under the new law.

The Army compiled an admirable record during its three decades of administration. But something more than competent protection was needed. Running a park was not the Army's usual line of work. The troops could protect the park and ensure access, but they could not fully satisfy the visitor's desire for knowledge. Moreover, each of the 14 other national parks established during this period was separately administered, resulting in uneven management, inefficiency, and a great lack of direction.

It was generally agreed by 1916 that the national parks needed coordinated administration by professionals attuned to the special requirements of such preserves. The creation of the National Park Service that year eventually as gave the parks their own force of trained men who were ordered by the Congress "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide I for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

A Park Service ranger force, including several veterans of Army service in the park, assumed responsibility for Yellowstone in 1918. Protection was complicated now by the growing number of visitors that toured the park in automobiles. The influx of cars meant that in time a significant part of the ranger force spent as much effort on controlling traffic as on protecting natural features. Increasingly sophisticated techniques and approaches were called for.

The appointment of Horace M. Albright to the post of superintendent in 1919 portended a broader approach to the management of the park than just protection of its features. Serving simultaneously in that office and as assistant to Stephen T. Mather, the Director of the National Park Service, Albright established a tradition of thoughtful administration that gave vitality and direction to the management of Yellowstone for decades. In 1929 he succeeded Mather as Director.

An innovation that the new Park Service brought to Yellowstone was "interpretation." Professional naturalists were hired to perform research and use the results of their study to give campfire talks or conduct nature walks for the public. Trailside museums, gifts of the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Foundation, supplemented these personal services. Eventually, as the needs of the public grew, programs became more sophisticated and went beyond merely explaining the natural features of Yellowstone. The naturalists now sought to interpret the complex web of life and the role of man in the natural order.

But the greatest contribution of the Park Service was a sense of mission that viewed a national park as an entity valuable for its own sake. This attitude signaled that the new protectors of Yellowstone would not function merely as caretakers, but would see that the park was managed and defended according to the best principles of natural conservation. During the 1920's and early 1930's the park's boundaries were adjusted to conform more closely with natural topographic features. Lands were also added to protect petrified tree deposits and increase the winter grazing range of elk and other wildlife. An offshoot of the boundary revision campaign was the establishment of Grand Teton National Park to protect the magnificent Teton Range—a movement in which the superintendent of Yellowstone, Horace Albright, played a crucial role. During the same period the Park Service helped to marshal the advocates of conservation to prevent the impoundment of Yellowstone's waters for irrigation and hydroelectric projects—reminding the Nation that Yellowstone's founders considered its wonders so special that they should be forever preserved from exploitation.

|

| Hot baths in Yellowstone. Primitive bathhouses, much as McCartney's at Mammoth (shown at top in the 1870's), eventually gave way to more elaborate accommodations like the Old Faithful Swimming Pool (bottom). |

|

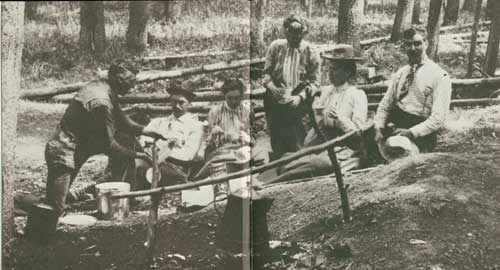

| Uncle Tom Richardson always served a good picnic to visitors who hiked into the canyon. |

|

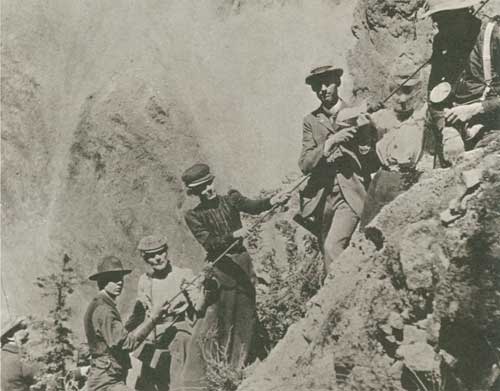

| Descending into the canyon by way of "Uncle Tom's Trail," 1904. These hikers are wearing typical sporting attire of the day. |

|

| A soldier explains how it works, 1903. |

|

| This well-dressed angler tries his luck from the "Fishing Cone" at West Thumb in 1904. |

Over the years a wide range of knowledge and new understanding were brought to the management of the park. More sophisticated views of wildlife and forest management helped ensure the perpetuation of the natural environment. A deeper understanding of the park's ecology in turn influenced the course of physical development, which was charted to minimize the impact of a large number of visitors on the environment while affording them the maximum opportunity to appreciate the Yellowstone wilderness.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

clary/sec6.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2009