|

YELLOWSTONE

"The place where Hell bubbled up" A History of the First National Park |

|

TOURING THE PARK

The experience of tourists in Yellowstone before the days of the family automobile was quite unlike that of modern visitors. The natural features that have always attracted people to the park appear much the same today, but the manner of traveling to the park and making the Grand Tour in the early days would now seem utterly foreign. "The old Yellowstone—the Yellowstone of the pioneer and the explorer—is a thing of the past," wrote Chittenden after automobiles gained free access in 1915.

To the survivors, now grown old, of the romantic era of the park who reveled in the luxury of "new" things, who really felt as they wandered through this fascinating region that they were treading virgin soil, who traveled on foot or horseback and slept only in tents or beneath the open sky—to them the park means something which it does not mean to the present-day visitor. And that is why these old-timers as a rule have ceased to visit the park. The change saddens them, and they prefer to see the region as it exists in memory rather than in its modern reality.

One of the greatest attractions of old Yellowstone was the opportunity to bathe in the hot springs. In a day when a hot bath was a luxury and people were less sophisticated about their medical needs, hot mineral baths were popularly believed to have curative powers—not to mention the simple pleasure of soaking in hot water. Hot springs around the world enjoyed long careers as "spas" for the well-to-do and resorts for health seekers. And it was the hot waters of Yellowstone that attracted many of its first pleasure-seekers. In July 1872, while the second Hayden Expedition was exploring the park, a crowd of at least 50 people enjoyed the waters of Mammoth Hot Springs and the delights of James McCartney's hotel—really a log shack—and ramshackle bath house—in actuality a set of flimsy tents sheltering water-filled hollows in the ground. Gen. John Gibbon patronized the establishment in 1872 and left a record of this peculiar form of pleasure:

Already, these different bathhouses have established a local reputation with reference to their curative qualities. Should you require parboiling for the rheumatism, take No. 1; if a less degree of heat will suit your disease, and you do not care to lose all your cuticle, take No. 2. Not being possessed of any disease I chose No. 3, and took one bath—no more.

|

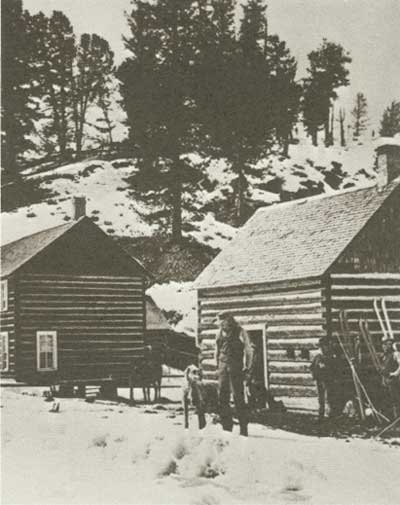

| Uncle John Yancey, with his ever-present dog, poses with guests in front of his Pleasant Valley Hotel in 1887. |

McCartney's facilities became somewhat more comfortable, then passed from the scene, but other such resorts appeared throughout the park. Bathhouse enterprises, offering springs of various temperatures and presumed medicinal powers, sprouted in the several thermal areas. They enjoyed a brisk business well into the 20th century, when changing modes of leisure reduced their popularity.

Fewer than 500 people a year came to Yellowstone before 1877, but thereafter the number of visitors increased steadily. Getting there in the first few years was a great problem. Tourists either transported themselves or patronized one or more of the intermittent transportation enterprises that carted them from Montana towns to the park. Once in the park they were on their own, finding sustenance during the early years only from a few concessioners or squatters who provided rude fare and minimal sleeping accommodations. Some early tourists were wealthy aristocrats, including a few titled Europeans who came well prepared to tour in grand style. But most of the earlier visitors were frontier people accustomed to roughing it—and they had to.

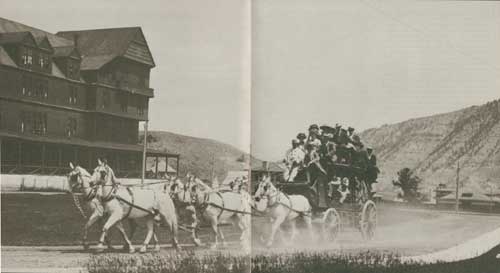

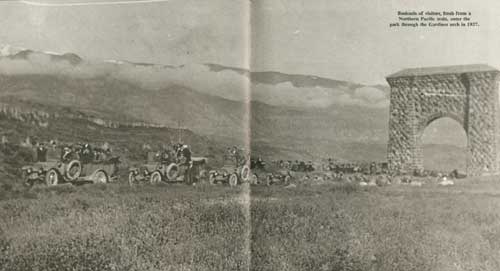

During the 1880's a visit to Yellowstone became easier. Access improved as the Northern Pacific Railroad reached Gardiner, on the north edge of the park. The Bozeman Toll Road Company, later known as the Yankee Jim Toll Road in honor of its colorful owner, also facilitated travel. The railroads, particularly the Northern Pacific, took an increasing interest in the tourist business of Yellowstone and were the financial angels of concessioner operations. After the early 1880's tourists could step down from a Northern Pacific train, and as part of a ticket package visit the prominent features of the park. Yellowstone acquired a number of the large, gaudy hotels popular as resorts in that day. Stage coaches took visitors on tours of the park, usually on a 5-day schedule. For the man with money, Yellowstone soon became a rewarding and enjoyable place for a vacation.

|

| During the Grand Tour, the stages stopped at places like Larry's Lunch Station at Norris. |

|

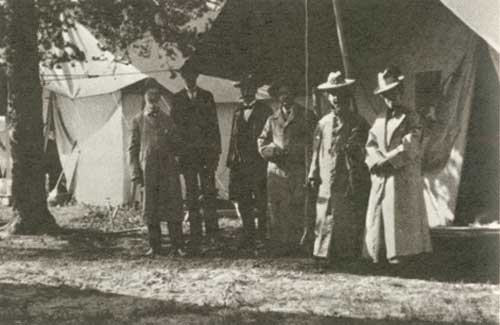

| Those wo declined the opulent grand hotels could stay in one of the park's tent camps, as this group did in 1895. |

|

| The Zillah was one of the first of the many tour boats that have plied Yellowstone Lake. |

|

| Another load of tourists arrives at Mammoth, 1904. |

Yellowstone was not yet a park for all of the people. Because of the expense of transportation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the travel industry in general was patronized mainly by the upper middle class—the affluent leaders of the industrial revolution. People accustomed to spending summers in Europe or at rich resorts like Saratoga Springs, N.Y., were the principal patrons of the Yellowstone package tours and "See America First" campaigns of the railroads. Though some people of lesser means did visit Yellowstone in the stagecoach days, the concessioners were dependent mainly on the "carriage trade." The difficulty of cross-country transportation and the expense of such a vacation for many years put the enjoyment of Yellowstone's wonders out of reach for those who could not go first class.

Even wealthy tourists—"dudes" as they were called in the park—faced a few inconveniences. Stagecoach travel could be bumpy and dusty, but the scenery more than compensated. The coaches frequently had to be unloaded at steep grades, giving the passengers an opportunity to stretch their legs and breathe in the cool air while following the vehicles uphill. Stagecoach accidents were a rare possibility. And, of course, there were a few holdups.

Despite the attention the popular press gave to robberies, there were only five stagecoach holdups in the park—four of them involving coaches on the Grand Tour. The second, in 1908, was the most impressive of the 20th century; in a single holdup one enterprising bandit fleeced 174 passengers riding 17 stagecoaches. Despite their cash loss, holdup victims were entranced with their robbers, for some were entertaining fellows who never seriously hurt the well-heeled "dudes." A holdup was an added bit of excitement to an already enjoyable tour. As one tourist remarked, "We think we got off cheap and would not sell our experience, if we could, for what it cost us."

Most visitors to the park exhibited that attitude. The minor inconvenience could not combine to eliminate the pleasures of "doing Yellowstone." Mingling with their own kind, breathing an atmosphere pretentiously reminiscent of the luxury resorts of the East, well-to-do vacationers easily accepted small discomforts while they visited Yellowstone's wonders.

The typical tour of Yellowstone began when the tourists, outfitted in petticoats, straw hats, and linen dusters (a few were persuaded to buy dime-novel versions of western wear) descended from the train, boarded large stagecoaches, and headed up the scenic Gardner River canyon to Mammoth Hot Springs. After checking into a large hotel they were free the rest of the day to sit in a porch chair (perhaps the same one that President Arthur had used); to spend their money on such souvenirs as rocks, silver spoons, photos, and post card views of frontier characters like Calamity Jane; and to fraternize with Army officers and frontiersmen like Jack Baronett, who had built the first bridge over the Yellowstone. Most of the visitors spent the afternoon touring the hot springs terraces, under the guidance of a congenial soldier or hotel bellhop, or bathing in the waters. Those who wanted to know more about the terraces, as Rudyard Kipling did in 1889, could purchase a guide to the formations "which some lurid hotel keeper has christened Cleopatra's Pitcher or Mark Anthony's Whiskey Jug, or something equally poetical." A heavy meal and retirement to a soft bed usually ended the tourist's first day in the park.

For the next 4 days, the tourists bounced along in four-horse, 11-passenger coaches called "Yellowstone wagons." They were entertained by the colorful profanity of the stage drivers, who urged their horses over the dusty roads of the Grand Loop. During the several halts at important natural features, the drivers further amazed their passengers with exceedingly imaginary explanations of the natural history. At midday there was a pause for refreshment at a lunch stop like Larry's at Norris. Each night there was a warm bed and a lavish meal at another grand hotel, such as the elaborately rustic Old Faithful Inn or the more conventional but equally immense Lake Hotel.

|

| Calamity Jane, a Montana character popular with tourists, received permission in 1897 to sell this post card portrait of herself in the park. |

Yellowstone did have a few genuine hazards for visitors. In 1877, as the Nez Perce Indians came through the park after the Battle of the Big Hole, they captured two tourist parties and killed or severely wounded a number of the people they encountered. The brief flurry of the Bannock War in 1878 raised fears of another Indian foray. These dangers were soon replaced by the occasional accidents of stagecoaching and the hazards that awaited the careless.

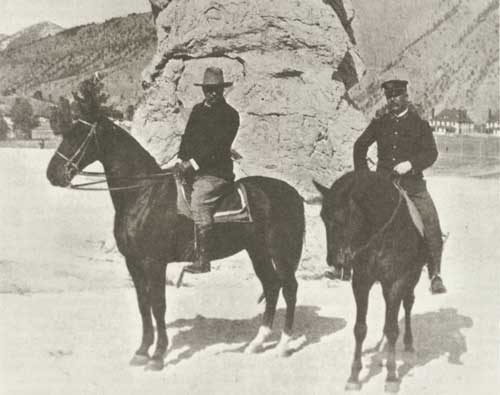

But the delights outweighed the perils. After the late 1890's people enjoyed the nightly spectacle of bears being fed hotel garbage and even helped with the feeding, few worrying about the effect on the bears or the danger to themselves. Some of the early tourists were even honored by the placement of their names on the map—in 1873 Mary Lake took the name of one of its first visitors, and in 1891 Craig Pass honored the first woman driven over it on a new road. And there was always the possibility that a tourist might rub elbows with a European nobleman or an American dignitary like President Theodore Roosevelt, who toured the park in 1903.

Some of the tourists availed themselves of optional pleasures. Boats offered peaceful tours of Yellowstone Lake, while back at Mammoth wildlife could be closely observed at the "game corral."

As a contrast to the elaborate hotels, rustic tent camps provided simple but comfortable accommodations among the trees. Uncle John Yancey's "Pleasant Valley Hotel" hosted teamsters and U.S. Senators alike. Uncle John, according to one patron, was a "goat-bearded, shrewd-eyed, lank, Uncle Sam type," whose unkempt hotel offered those of simpler tastes welcome relief from the opulence of the great resorts in the park. And one guest noted that "A little bribe on the side and a promise to keep the act of criminality a secret from Uncle John induces the maid to provide us with clean sheets." The affability of Uncle John was later matched by the whole some friendliness of Uncle Tom Richardson, who served splendid picnics at his trail into the canyon.

|

| President Theodore Roosevelt paused at Liberty Cap. Mammoth, with an aide during his long tour of Yellowstone in 1903. |

|

| This group, visting in 1904, seems unimpresed by the thermal spring. |

|

| Busloads of visitors, fresh from the Northern Pacific train, enter the park through the Gardiner arch in 1927. |

|

| Though automobiles drove horse-drawn coaches from the roads, vistiors who still wanted a Grand Tour could go by "motor coach," as these Italian bishops did in the 1920's. |

|

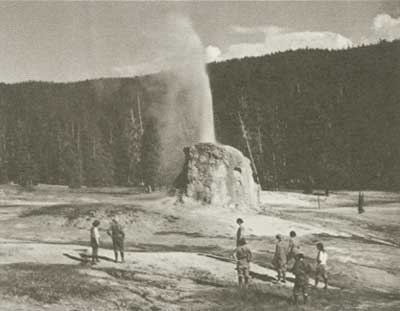

| Lone Star Geyser in the 1920's. |

Altogether, touring Yellowstone was a pleasant, if arduous, experience. But the reactions of some visitors were not always what might be expected, according to a stage driver: "I drive blame curious kind of folk through this place. Blame curious. Seems a pity that they should a come so far just to liken Norris to hell. Guess Chicago would have served them, speakin' in comparison, just as good." In keeping with the unspoken rules of the wealthy tourist's social class—which required a calm demeanor at all times—few of the many photographs taken during Grand Tours show smiles on the dignified faces posed among the natural wonders. Yet the "dudes" carried home memories of experiences and sights that were unforgettable. They recommended the tour to their friends, and each year more of them came to Yellowstone to gaze upon its wonders.

But as increasing wealth and technological progress enabled more of the public to travel, Yellowstone could not remain an idyllic resort for the few. The first automobile entered Yellowstone in 1902, only to be evicted because regulations had already been adopted to exclude such conveyances. Yet "progress" could not be staved off forever. Over the years the pressure mounted. Political favor swung toward cars, and many people foresaw benefits in admitting them to the park. Accordingly, in 1915, the Secretary of the Interior made the fateful decision, and on July 31 of that year cars began to invade Yellowstone. Although they were severely regulated and a permit was expensive, their numbers increased steadily, forcing the concessioners to replace their stages with buses. Horses were relegated to the back country, while many of the tent camps, hotels, lunch stations, and eventually all but one of the transportation companies disappeared. They were replaced by paved roads, parking areas convenient to scenic attractions, service stations, and public campgrounds to accommodate the growing number of motorized visitors.

But the automobile changed more than just the mode of touring the park. No longer just a vacation spot for the wealthy, Yellowstone became a truly national park, accessible to anyone who could afford a car. Without resorting to the concessioners, visitors could now pick their own way around the park, see what they wanted, take side trips, and camp in one place as long as they liked. But never again would a visitor be a pioneer explorer, facing an unknown wilderness, leaving his name on the map. For better or worse, a new day was beginning. The time lay far in the future when the car would appear as an enemy threatening to suffocate the park; meanwhile, it was all to the good. Thanks to this noisy, smoking, democratic vehicle, Yellowstone was now truly a "pleasuring-ground" for the people—all of them.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

clary/sec7.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2009