|

OLYMPIC National Park |

|

The Mountains Are Formed

THE STAGE IS SET

Olympic geology has not been fully explained. Geologists have attempted to piece together the rock records, but the story is not yet complete. The following describes the probable sequence of events.1

1Adapted from a paper by Wilbert R. Danner.

THE FIRST SEA

Our story begins about 120 million years ago. There were no Olympic Mountains then; instead, all of western Washington was covered by a shallow sea. Streams carried mud and sand into the sea and these settled to the bottom. During millions of years at least 10,000 feet of sediments accumulated on the sea floor. Eventually, these compacted into shale and sandstone. Lava that poured out of fissures in the sea floor from time to time became buried in the sediments.

THE FIRST MOUNTAINS

The great mass of the Pacific basin was pressing against the continent. This caused the under-water edge of the continent to fold upward into mountains above sea level. The rock layers were folded, and crumpled. The great pressures changed the shale to slate and made the sandstone harder. More millions of years passed while the mountains were lowered considerably by erosion.

THE SECOND SEA

The land subsided again about 60 million years ago and was flooded by the sea once more. Immense quantities of lava poured out of fissures onto the sea floor. It piled up in large masses with at least 5,000 feet accumulating. Under water, the flowing lava cooled quickly to form masses with pillowlike structures. Several hundred feet of sediments settled upon the lava before the second sea withdrew.

THE SECOND MOUNTAINS

The sea bottom was elevated into mountains again and much of the new sediments probably eroded during this mountain phase.

THE THIRD SEA

Again the land subsided beneath the level of the sea and new sediments accumulated on top of the older rocks.

THE THIRD MOUNTAINS

About 20 million years ago western Washington was pushed up into a great range of mountains that extended from Cape Flattery southeastward to the eastern part of the State. At the same time the land to the north and to the south was depressed and remains depressed today as the Juan de Fuca Strait and Chehalis Valley, respectively.

These ancestral Olympic Mountains received another upward push about 5 million years ago. This coincided with the building of the Cascade Mountains and the down-folding of the land in between to form the Puget Sound trough. Now the Olympics were isolated, having lowland on all sides.

EROSION

Earth forces build mountains, and water slowly carries them back to the sea. So it has been since the first rains fell upon the cooling earth. Each mountain phase in Olympic history was characterized by erosion. Thousands of feet of sedimentary rocks have been removed. Only the older rocks remain, for these were the bottom layers.

ROCKS

The rocks that were formed in the first sea, now mostly slates and hardened sandstones, are the oldest rocks known in the Olympics and make up the greater part of the mountains. All the rock inside a horseshoe-shaped line running from the village of Sappho east to Lake Crescent, Lake Mills, and Deer Park, then south to the west side of Mount Constance and the north end of Lake Cushman, then west to Lake Quinault are of this age. The horseshoe-shaped outer rim of the mountains outside this line is mainly of basaltic lava deposited in the second sea.

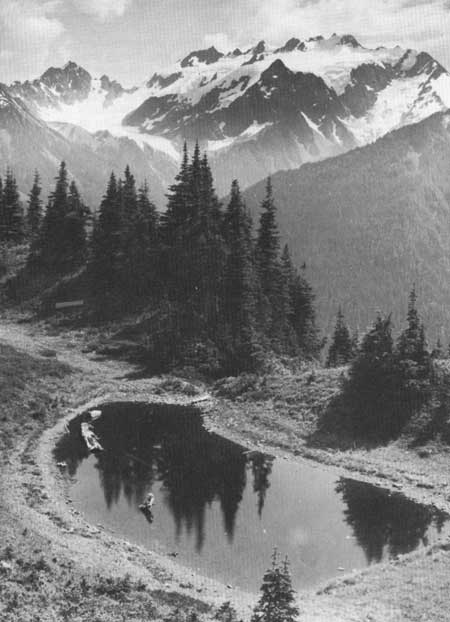

MOUNT OLYMPUS, FROM HOH-SOLEDUCK DIVIDE; BLUE GLACIER IN THE UPPER LEFT. |

GLACIATION

The next important geological events started about a million years ago. As the climate of the world became colder, a great ice sheet formed to the north and moved down across Canada into the United States. There were periods when the climate warmed and the ice retreated. It advanced again when temperatures lowered during tens of thousands of years. The sheet moved southward at least four times during the last million years.

At the same time, valley glaciers flowed out of the mountains of British Columbia, joined forces, and formed a piedmont glacier that moved southward into Puget Sound. A lobe of this glacier branched off and flowed westward through Juan de Fuca Strait. This piedmont glacier, at least 3,000 feet thick, rubbed the northern edge of the Olympic Mountains and sent ice fingers up the valleys. It brought granite boulders from the north and dropped them along the way when it melted. Some of these granite boulders have been found near Camp Wilder, 25 miles up the Elwha River Valley, and as high as 3,000 feet on the side of Mount Angeles.

As the ice moved west along the northern border of the mountains it plowed and scraped and deepened an ancient valley that filled with water when the ice melted. This is Lake Crescent. These and numerous other telltale marks attest to the work of a thick ice sheet.

Approximately 11,000 years have elapsed since the retreat of the last northern ice sheet from Washington.

With the onset of colder climate, valley glaciers also formed in the Olympic Mountains. They flowed from high mountain cirques down the valleys, probably filling the valleys during times of greatest ice volume and becoming thinner and shorter during times of warmer climate. Like the larger ice sheets from the north, the valley glaciers of the mountains must have advanced and retreated periodically. The greatest advance was as much as 25 to 40 miles in the Hoh, Queets, and Quinault Valleys.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |