|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

Man Comes—And Goes

If you spend much time at Rock Harbor, chances are you will take a walk out toward Scoville Point on the Stoll Trail. About halfway to the point you will pass three small pits in the rock—a small sample of many pits excavated on Isle Royale by Indians, hundreds of years ago, in their mining of copper. Collectively, they represent man's first appearance on this young island.

In many ways, Indian use of Isle Royale was like most later human activity here: it was seasonal and exploitative, and finally it was abandoned. Unlike other animals, man has never been able to live long-term and harmoniously with this rigorous, remote land.

Minong Ridge, near McCargoe Cove, is the site of both prehistoric Indian copper diggings and a late 19th-century mining operation of the Minong Company. (Photo by Robt. M. Linn) |

As we have seen, plants followed close after the retreat of glacial ice out of the Superior Basin, and animals followed the plants. Close upon the heels of animals came man, the hunter. By 6000 or 7000 B.C., possibly earlier, Indians had reached the north shore of the lake. We don't know when they first ventured the 15 or 20 miles to Isle Royale; but by about 2000 B.C. they were mining copper on the island. (Wood from a pit near Lookout Louise has been radiocarbon-dated at 2160 B.C. plus-or-minus 130 years.) Using rounded beach cobbles, they hammered the rock away from the pinkish veins of pure copper. Perhaps, too, they used fire to heat the rock and make it more friable, though this is uncertain. Probably these early visitors came in small groups during the summer, worked a number of pits, and returned to the mainland for the winter. Quite possibly they burned off the vegetation, as white miners later did, to find the copper veins more easily. They used the malleable metal for spear points and other implements.

For about 1,000 years, Indians mined copper on Isle Royale, the Keweenaw Peninsula, and other areas around Lake Superior. Some of this material, presumably through trade, found its way to southern Manitoba, the St. Lawrence Valley and New York, and northern Illinois and Indiana; but the chief area of use was eastern Wisconsin.

Then, on Isle Royale, the archeological record goes blank until about 300 B.C. By this time, little mining was being done here, though some use of copper continued. Much copper must have remained in circulation, however, for it was during the period from 500 B.C. to 500 A.D. that the Hopewell Indians of southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois used Lake Superior copper to make numerous highly artistic ornaments. We know that Indians used Isle Royale rather extensively during these centuries, since their occupation sites have been found at Indian Point (at the mouth of McCargoe Cove), Chippewa Harbor, Merritt Lane, Washington Island, and other places. Bones uncovered at the Indian Point site indicated some of the contemporaneous animal life: caribou, moose, beaver, lynx, snowshoe hare, muskrat, loon, bald eagle, sturgeon, shorthead redhorse sucker, and turtle.

Judging from the number of sites found, the period from 800 to 1600 saw the peak of Indian activity on Isle Royale. After the arrival of Europeans in the Great Lakes area, Indian culture began to disintegrate and their numbers declined. By the 1840's, when white miners came to Isle Royale, the only Indian encampments were one at Sugar Mountain, where they tapped maples for the sap, and a seasonal fishing camp on Grace Island.

In their 4,000 to 5,000 year use of Isle Royale, Indians apparently left only small pits in the rock as lasting marks on the landscape and life of the island. If they burned the plant cover in their search for copper or eliminated beaver or other animals in fur-trade days, there is no evidence of this today. They seem to have left the forests full of game and the waters full of fish.

The same cannot be said quite so confidently for those who followed, though modern man's record has been better here than it has in most places. During the 19th and 20th centuries, people have come for fish, copper, lumber, and finally for that most fragile and elusive of natural resources—wilderness. Even that last quest has left its mark on the land.

In historic times, fishing has been the most enduring economic activity on Isle Royale. The many reefs and miles of shoreline, as well as great range of water depths and several types of bottom material, provide for the varying seasonal needs of lake trout, whitefish, and herring—the chief species sought. Sheltered harbors give fishermen bases from which to operate.

Commercial fishing began here before 1800, when the Northwest Fur Company took fish from the north side of the island to supply its stations at the western end of Lake Superior. In the late 1830's, the American Fur Company established seven fishing stations on Isle Royale. Their catches were good, but the economic depression of 1837-41 dried up their markets. Since that time, commercial fishing on Isle Royale has continued largely as an individual enterprise, and for the most part it has been successful. Nearly every sheltered cove has had its fish houses and log cabins, where fishermen and their families lived from spring until fall. Most returned to mainland towns in winter, but a few hardy souls lived here year-round. For various reasons, fishing declined through the present century. In 1972, only four commercial fishermen still operated on the island, partly as employees of the National Park Service, which strives to maintain some of this activity as an integral part of Isle Royale life.

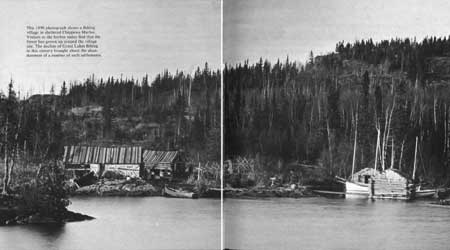

This 1890 photograph shows a fishing village in sheltered Chippewa Harbor. Visitors to the harbor today find that the forest has grown up around the village site. The decline of Great Lakes fishing in this century brought about the abandonment of a number of such settlements. |

Lake Superior, though productive, has not remained the rich source of fish it was when Europeans first settled here. In the 1880's, when fishing was booming on Isle Royale, a decline in whitefish catches was noticed. Whether overfishing was the main problem is not known, but whitefish numbers have remained low to the present.

Man's activities were directly responsible for a more recent shock to the Lake Superior ecosystem: the building of the Welland Canal allowed sea lampreys to bypass Niagara Falls and enter all the upper Great Lakes. By 1952, these eel-like, parasitic animals had appeared in Lake Superior. They attacked primarily the lake trout, and within a few years had decimated its populations. Fishermen were forced to turn to the herring, a smaller and less profitable species. Eventually, use of chemical poisons in spawning streams brought the lamprey under control and the lake trout recovered to the point where a small take became permissible. But herring remained the chief support of the declining Lake Superior fishery.

The introduction of smelt into the Great Lakes about 1912 was deliberate, but this, too, may have had some adverse effects. Smelt proliferated and now, in spring, run up Lake Superior streams in enormous numbers. Fried smelt make a tasty dish, but, according to many fishermen, they eat large numbers of eggs and fry of other fish, including the larger commercial species. This belief and other aspects of smelt ecology still await scientific study.

Of all economic enterprises on Isle Royale, copper mining undoubtedly has had the greatest environmental effects. The chief impact came from the use of fire to remove the plant cover from the rocks. As any bushwhacker today discovers, the underbrush is thick in many places. Copper prospectors burned thousands of acres to aid them in their search. In the next chapter we will trace some of the extensive biological effects of such fires. Miners also cut wood for fuel, building material, and mine props, and made clearings for settlements.

Post-Indian mining occurred only in the 19th century, during three periods of activity. The first lasted from 1843 to 1855. Much exploration was carried out, but only small quantities of copper were obtained, under dangerous and uncomfortable conditions. Two of the more easily seen mines from this period are the Smithwick Mine, a small, fence-rimmed excavation on the Moose Trail near Rock Harbor Lodge, and the Siskiwit Mine, which is on the north shore of Rock Harbor opposite Mott Island.

Interest revived between 1873 and 1881, when larger (but fewer) operations, benefitting from improved mining technology and better transportation, were carried out. The largest of these was the Minong Mine, near McCargoe Cove. Following the lead of the prehistoric miners, who had dug hundreds of small pits in Minong Ridge, workers of the Minong Company sank two shafts and blasted large quarries in the ridge. At its peak, production here required 150 men who, with their families, formed a substantial settlement. There was a blacksmith shop, a stamp mill, an ore dock, and railroads between mine, mill, and dock. Today the mine area looks like the scene of some ancient bombing raid. "Poor rock" piles lie huge and bare in the forest. Pits and quarries yawn eerily in the side of the ridge. Rusted, twisted tracks go nowhere on their grass-grown roadbeds. Nothing remains of the town. Its site is now occupied by a lovely open forest of aspen, its openness the only hint of man's former presence.

Pete Edisen with a record catch—16 boxes of lake herring—in 1965. (Photo by P. A. Jordan) |

The other substantial operation of this period was the Island Mine, about two miles northwest of the head of Siskiwit Bay. A town was laid out on the bay shore, and this became the county seat of the newly established Isle Royale County (now a part of Keweenaw County). But fire, low copper prices, and poor deposits cut short the life of the mine. Nothing remains of this town, either; but the Island Mine Trail, which follows the old road to the mine, passes by the shafts and rock piles, half-screened by the surrounding forest.

The final quest for copper lasted from 1889 to 1893 and centered in the Windigo area. A town was built at the head of Washington Harbor and extensive diamond drilling was conducted to locate the metal, but the deposits proved too poor. The only production from these efforts was geological data, on which much geological understanding was subsequently based. Thus ended man's 4,000-year search for copper on Isle Royale.

The island's isolation and its shallow soil, which does not allow large stands of tall trees to develop, may have been the chief factors that saved it from intensive lumbering. Aside from the cutting done by miners, there were only two significant episodes of lumbering. In the 1890's a Duluth company cut white-cedar and pine along Washington Creek and floated the logs down to Washington Harbor, where they were held in by boom chains. This venture ended when a big storm caused Washington Creek to flood and break the log barrier, sending the harvest out into Lake Superior.

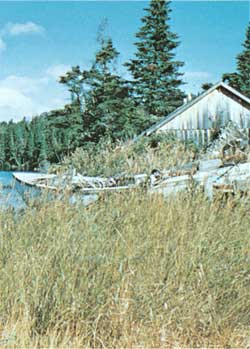

On the shore of Wright Island an abandoned fisherman's home is a reminder of the days when Isle Royale's fishery thrived. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Fire ended the other operation. In the early 1930's, while land acquisition for the newly authorized park was underway, the Consolidated Paper Company was logging spruce and fir from its holdings at the head of Siskiwit Bay. In July 1936 a fire started near the lumber camp and eventually burned nearly a quarter of the island. Though 18,000 cords of pulpwood stacked near the bay were saved, much of the company's forest holding was left a charred wasteland.

While men sought, rather unsuccessfully, to exploit the island's natural resources commercially, a nonconsumptive form of exploitation—one that would eventually assume dominance—was beginning. Since the 1860's a few tourists had been coming to Isle Royale to enjoy its fishing and its tranquil, remote, romantic wildness. During the early 1900's, with the rapid growth of midwestern cities and the introduction of lake excursion boats, tourism picked up. Resorts were built on Washington Island and at Windigo, Belle Isle, Tobin Harbor, and Rock Harbor. People acquired cottage sites, particularly on the islands and long peninsulas at the northeast end of the island.

The appreciation of cottagers and tourists for Isle Royale's peace-giving blend of woods and water eventually crystallized into a movement to make the island a park. At first a state park was visualized, but later sentiment favored a national park. In 1922, Representative James C. Cramton of Michigan made the proposal in Congress. After a long battle between proponents and opponents, Congress in 1931 passed a bill making Isle Royale a National Park project. Lands were gradually acquired and several Civilian Conservation Corps camps were set up to construct trails, fire towers, and the necessary buildings. Isle Royale National Park was formally established in 1940 and was officially dedicated in 1946. Then, as now, occasional foul weather complicated travel to the island. The Park Service director and assistant director were unable to fly from Houghton for the dedication ceremony; 1,000 others made it by some means.

Isle Royale's preservation as a park was the achievement of many people, but the man who first planted the idea in many minds was Albert Stoll, Jr., a Detroit newspaperman. After a visit to Isle Royale in 1920, he wrote a series of editorials, for the Detroit News, promoting park status for the island. The trail now memorializing him leads past the Indian pits mentioned at the beginning of this chapter to a plaque about Stoll at Scoville Point, thus touching on the first and also the most recent phases in man's long relationship with this island.

Most of Isle Royale National Park is kept in a wild state, with a minimum of visitor developments such as this boardwalk through the white-cedar swamp on Rock Harbor Trail. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

What did the people of the United States inherit from the prehistoric past through establishment of this park? Remarkably much, we can conclude. Man may have eliminated the lynx and the marten from the island by trapping, and he probably had diminished the fish populations around its shores. He had introduced some non-native plants such as clover and had made clearings in the forest. But generally his activities had not disturbed the normal workings of nature. His fires, though concentrated in time and far reaching in their effects, apparently had the same long-term results as the lightning fires that surely have burned this island since it first bore trees. For some decades he had not hunted the animals but had let predators, prey, and vegetation find their natural balance. He did introduce the Norway rat and white-tailed deer, but these did not survive long. In 1946, excluding a few buildings and trails, the island scene and its plant and animal components were probably nearly the same as they had been four centuries earlier, before Europeans arrived here and set eyes on the "floating" island.

To be sure, however, some "natural" changes had occurred, particularly among the larger animals. Woodland caribou, probably residents of the island much of the time since early post-glacial days, disappeared about 1927. Moose, probably present at various times in the past but absent during the 19th century, reappeared early in the 20th. Coyotes were seen and heard through the first half of the 20th century, but disappeared about 1955. And wolves, which no doubt hunted moose and caribou here in distant centuries, were not regular residents during the 19th and early 20th centuries but be came firmly established in the 1940's. Thus change has continued, with or without the presence of man, since the island was born.

As commercial fishing declines and cottage leases expire, old ways of life on Isle Royale fade away. But in some ways the pattern of human activity remains the same. Visitors come for a few days and return home. Park Service people and a few others come in spring and leave in the fall. No one stays permanently. For a week or a season the island attracts us, but in the end the wild forces beneath the beauty send us back across the water. Only for moose and beaver, wolf and raven, spruce and fir is Isle Royale a true home.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |