|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

Fire, Wind, And The

Changing Forest

Walking the middle section of the Greenstone Trail, one passes through dense young forests of birch and aspen. Here and there a dead pine stub rises above the living trees, and charred stumps twist upward among the white trunks. All these are the present signs of the most destructive event on Isle Royale in this century, and of nature's enormous powers of recuperation.

In the summer of 1936, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan lay in the grip of a deep drought. On Isle Royale, slash from logging operations in the Big Siskiwit River area covered the ground. On July 25, man or lightning started a fire near the logging camp at the head of Siskiwit Bay. The fire eventually burned a large area west of the camp, jumped northward and consumed forests all the way from Lake Desor to Moskey Basin. Not until mid-August, when a shift in wind and heavy rains helped the 1800 firefighters, was the fire put out. It left 27,000 acres a jumble of charred logs.

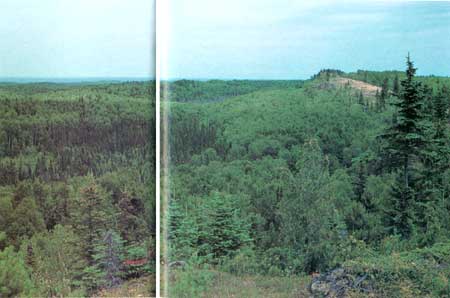

But the dense green forest now covering these slopes shows that nature can cope with fire. Fire, in fact, is a part of nature, an element to which plant and animal species have become adapted. Other forces, too, attack the forests, and form a part of the total pattern of life. Wind blows trees down; insects devour leaves and tunnel through trunks; disease enters; animals browse saplings or cut trees. All these agents keep the forests in slow turmoil, in continual cycles and sub-cycles of destruction and re-creation.

The 1936 burn, seen from Greenstone Ridge, is undergoing a slow process of recovery. |

Indeed, more than half of the forest on Isle Royale is in some stage of recovery from fire and other destructive forces—not yet, that is, in a mature stage in which certain tree species have attained long-term dominance. The process of succession toward that state is continuous; but disturbances, particularly the strong winds, work against the attainment of a mature, stable forest over the whole island. Instead, there is a patchwork of forest types, generally following the linear pattern of ridges and valleys but made more random by the chance effects of destructive forces.

On most of Isle Royale—that part most affected by the layer of cool, moist air over Lake Superior—the trend is toward a forest of white spruce and balsam fir. Sizable patches approaching this type, though containing much birch and aspen, occur near the shorelines. Forests of old aspen and paper birch in which spruce and fir have not yet become dominant occupy a larger area. On the central ridges in the southwestern part of the island, where soils are fairly deep and the climate is somewhat warmer, mature forests of sugar maple and yellow birch have stood for a long time, apparently little affected by fire. This type and spruce-fir represent the two "climax" forest types on Isle Royale. Most of the 1936 burn area should progress toward these two kinds of forest. Other types on the island are swamp forests of black spruce, white cedar, and fir; and small areas of jack pine on some rocky, south-facing slopes and ridgetops. These forests may eventually join the dominant white spruce-fir forest, as swamp soils dry and spruce grows up in the shade of the pines.

These spruces and firs will eventually replace the birches under which they started. (Photo by R. Janke) Thimbleberry is a shade-tolerant plant of the forest floor. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

When fire strikes hard, burning trees as well as ground cover, it sets back succession to an early stage. Where fire is particularly intense, it may consume all organic matter in the soil and, together with the erosion that often follows, strip the surface down to bare rock. But in most places some ash-covered soil is left. From this, grasses, fireweed, pearly everlasting, and other herbaceous plants soon sprout, speckling the blackened earth with green. These are followed by woody plants: thickets of hazelnut, seedlings of juneberry, pin cherry, and choke cherry. Paper birches, aspens, and mountain ashes, killed aboveground, resprout from stem and roots below ground, sending up several shoots in place of each single stem burned. In a few years an open grassy area, dotted with shrubs and small trees, has developed. Grasshoppers, flies, bees, chipping sparrows and song sparrows find such places to their liking.

As shrub clumps and tree sprouts grow over the fire-felled logs, making a dense tangle of greenery, snowshoe hares take advantage of the combination of food and cover, and red foxes take advantage of the snowshoe hares. Moose find a lot of browse in such places, and wolves find moose.

If conditions are right, the trees grow rapidly. Gradually the shrubs are shaded out, the logs rot, and lower tree branches die, reducing the amount of food that hares can reach and eliminating many of their hiding places. After 30 years or so, the trees may be too tall to supply food even for moose. At this stage, the forest is a monotonous, even-aged stand of close-packed young birches and aspens, with a few small spruces and an occasional fir underneath, the result of seeds blown or carried in from older forests. Here and there a white pine shoots up, perhaps one day to tower above all the other trees. The forest floor, now fairly well shaded, is likely to be covered with thimbleberry, large-leaved aster, bracken fern, or wild sarsaparilla, with perhaps a few bunchberries and bluebead-lilies underneath them. As might be expected from the lack of variety in habitats, animal life is rather scarce. One may see only an occasional red squirrel or moose, and a few birds such s red-eyed vireos, ovenbirds, and chickadees. But variety will grow with age.

This stage may be slow in developing, however, because of heavy browsing by moose. Aspens and birches in some of the 1936 burn area are still quite suppressed. Through all stages of growth, moose strongly affect the structure and composition of the forest.

On some burned areas, particularly dry slopes and ridgetops, spruce and jack pine, rather than birch and aspen, are the pioneer trees. In such places there may be little change in the tree species present as the stand grows older.

In a typical stand of young birches and aspens, competition among the trees for water, light, and minerals gradually thins the stand as the survivors grow taller. Spruces and firs, now germinating more abundantly, begin to create a dark layer beneath the birches and aspens. The firs, however, will be under continual pressure from moose browsing, and few will "escape" to become part of the overstory.

A hundred years or more after the fire, the spruces, along with some firs, may gain dominance over the deciduous trees. Gradually the aspens reach the end of their life span. Where the conifers stand close together the aspens leave few offspring, for here the forest floor is too shady for survival of the seedlings. Paper birches, usually more numerous, survive longer as a forest component, but their seedlings and root sprouts have the same problem. Given enough time and lack of disturbance, most of the birch would disappear, too, and a dark forest of spruce and fir would develop. For a number of reasons (which were stated earlier and which we will examine later) this seldom happens on Isle Royale.

These maturing forests, with their mixture of conifers and broad-leaved trees, provide homes for much more wildlife than do the dense young stands. Red squirrels, attracted by the seeds and thick cover of conifers, become common. Warblers, thrushes, red-breasted nuthatches, winter wrens, white-throated sparrows, and many other birds occupy the variety of niches now available.

If the area is above the influence of the layer of cool moist air that lies over Lake Superior, it may change from a young paper birch-aspen stand into a sugar maple-yellow birch forest rather than spruce-fir. In this case, a dense crop of sugar maple seedlings develops under the birches and aspens, and the maples, with a sprinkling of yellow birches, eventually take over. In some areas, red maples, red oaks, and white pines may be important in the successional stages. In the mature maple-birch forest, which shelters a few conifers in moist places, squirrels and birds are also much more abundant than in the earlier stage of the forest, though this type seems to have less variety of wildlife than does spruce-fir forest.

The relative variety and abundance of life in the later stages of forest succession is due partly to the several layers within them. There is the canopy, high above the ground and struck with sunlight. There is an understory, composed mostly of young of the canopy trees. There are shade-loving shrubs and small plants near ground level. But the variety is due also to destructive forces, which create openings in the forest and thus provide additional habitats.

Snowshoe hares abound on old burns where shrubs and fallen trees make thick cover. (Photo by R. Janke) |

Besides fire—which burns small areas much more often than large ones—wind, insects, larger animals, and disease contribute to the constant change in forest structure. Wind, aided by thinness of soils and trunk weakening diseases, probably takes the lives of more trees than does any other agent. Over most of Isle Royale, the last glacier was stingy with its deposits, and there has not been enough time since then for deep soils to develop. The shallow root systems of spruce and fir, anchored in thin, often wet soil over rocks, provide poor resistance to strong winds. Particularly during fall storms or high winds in winter, when trees may be laden with ice or snow, trees fall by the hundreds. Balsam fir is frequently afflicted with heart rot and this adds to its susceptibility, often causing it to snap off in high wind. Blowdowns are thus a common sight on Isle Royale, creating barriers for the hiker, cover and food for animals, and many openings in the forest.

Feeding by the aspen leaf roller (caterpillar of the large aspen tortrix moth) caused heavy damage to aspen forests in the early 1970's. (Photo by R. Janke) |

Insect outbreaks periodically add their effects to those of other agents of destruction. In the early part of the 20th century many tamaracks were killed by larch sawfly larvae, which eat the needles, and tamaracks are still scarce on the island. In the 1930's the spruce budworm destroyed many firs (which it prefers over spruce), in the same manner, but it is apparently doing little damage today. The chief insect scourge of the early 1970's was the large aspen tortrix (a close relative of the spruce budworm), which eats the leaves of aspen before making its cocoon inside a rolled-up leaf. Many acres of aspens, particularly on the southwest end of the island, were defoliated; but most of the trees leafed out again. On a small scale every year, and on a large scale some years, insects contribute to the constant forest turnover.

Less dramatic but perhaps more important in the total effect on trees are diseases. Heart rot, mentioned earlier, is caused by fungi that enter the heartwood of trees. White pine blister rust, another fungus, kills white pines by destroying needles and girdling stems. Hundreds of other fungi, bacteria, and viruses attack trees, continually challenging their fitness to live and to dominate the area they shade.

In this view from Minong Ridge near Linklater Lake, spruces and firs form dark patches amid the lighter aspens and birches—a typical pattern on Isle Royale. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

The role played by vertebrates in forest change is especially evident on Isle Royale. Moose and beaver drastically affect the structure and composition of the forest, while other mammals, though by comparison unimportant agents, nevertheless have measurable effects.

In winter, moose feed extensively on the foliage and twigs of fir. The island's high population of moose has left browse lines on most stands of fir, denuding many of the branches from the snowline to about eight feet above the ground. They often break the tops of small firs to reach the foliage there. This heavy browsing of fir has the net result of decreasing the fir component of the forest and increasing the proportion of spruce, which moose do not eat. Moose are also especially fond of aspen, mountain-ash, paper birch, pin cherry, mountain maple, and red maple; in some areas they keep saplings of these species perennially browsed back to shrub height. Earlier in this century, moose virtually removed the American yew, an evergreen shrub that once formed dense thickets on the island. Only on certain offshore islands, such as Raspberry and Passage, where moose seldom or never go, does yew continue to flourish. Elsewhere, since moose eat the more conspicuous individuals, only small specimens of yew can be found. In a later chapter we will further examine the moose-vegetation relationship on Isle Royale.

Two moose forage in the shallows of Washington Creek. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Beavers, of course, dramatically change the forest in the vicinity of their ponds, which on some parts of Isle Royale form a large part of the landscape. Trees are killed in the flooded area, and many aspens and birches within 150 feet or more of the pond are felled. The beavers thus maintain open areas in the forest, and to some extent encourage the growth of spruce and fir through the removal of aspen and birch. Intense suckering—sprouting of shoots from the base of a trunk—occurs when beavers cut aspens.

Snowshoe hares feed on many of the same plants that moose eat; but their comparative effect on vegetation is small. As with moose, they have the greatest impact on the forest in winter, when only woody stems, twigs, and bark are available to the hares. Since they can reach about two feet above the surface of the snow, they browse up to a height of four or five feet.

Insects, birds, and mammals also play a productive role in the forest. Insects aid in seed production by pollinating flowers. Birds and mammals disperse seeds, sometimes inadvertently, and aid in germination by burying some and softening the coats of others in their digestive tracts.

The forest, then, is an ever-changing mixture of plants, acted upon and influenced by all the forces of the environment, including the whole spectrum of animal life that dwells within it. While hiking on Isle Royale, particularly on trails that cut across the topographic grain, one sees a mosaic of forest types and stages: damp shoreline forests of fir, spruce, and birch dripping with beard moss; open, shrub-dotted stands of tall aspens and birches; dense, dark swamps of black spruce and white-cedar; sun-baked grassy ridgetops, slowly recovering from some long-ago fire. Each part of the forest is coming from somewhere and going somewhere. None of it is standing still.

One purpose of national parks is to preserve places where nature is allowed to operate as much as possible without the interference of man. On Isle Royale, this laissez-faire policy extends even to fire. Though human-caused fires are put out, lightning fires are allowed to burn unless they threaten some campground or other developed area. Most of these are very small and go out soon. (This does not mean that fires are not carefully watched, however. Fire flights and fire tower operators quickly spot and follow the course of all fires.) Similarly, insect outbreaks are not checked. Nature eventually does this herself, through the effects of weather, food shortage, and predation by other insects and birds. For instance, the population explosion of the large aspen tortrix in the early 1970's was inhibited, if not checked, by an army of birds, including red crossbills, blackbirds, many kinds of warblers, and even woodpeckers that awkwardly crept out on the twigs and picked caterpillars off the leaves.

On Isle Royale, as in all wild places, the forces of creation and destruction work in some ultimate balance. This equal struggle of life against death creates many different patterns of existence in the woods and waters of this lonely, harsh, beautiful island.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |