|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

The Herring Gull: Shorelines

On his way down the shore of Rock Harbor, the hiker pauses to admire the scene. Under his feet, lichen-patterned rocks slope down to the lapping water. Down the trail, dark pointed conifers crowd the shore. And beyond the trees, Rock Harbor and its flanking string of islands stretch away to unknown places. Maybe before he leaves the island he will try for trout along this shore, and maybe he will get out to the lake side of those fringing islands to explore the wave-struck rocks. The possibilities of his adventure are endless. But right now he wants to get to Three Mile Camp to make his first dinner. He adjusts the new red pack on his back and continues down the trail.

(Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson)

High in the air above him, a female herring gull surveys the same scene. At the moment, only one aspect of it interests her—the food it might offer. She has two downy young in a nest on Burnt Island, and their demands are incessant. Her keen, cold yellow eyes catch a red spot moving through the trees; but the hiker is not eating. She glides down over the docks at Rock Harbor Lodge. The black ducks are there, paddling along the shore, but no one is feeding them. She turns and flies across Rock Harbor toward Raspberry Island.

A gull rests on a natural bridge on the rugged shore of Raspberry Island. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

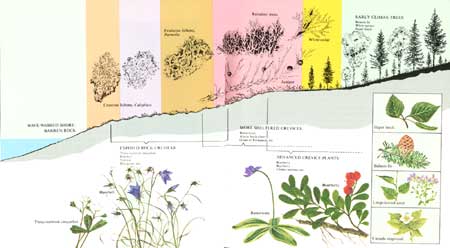

On the outer side of the island the gull lands on a big rock. All along this shore the gray basalt slopes down from the thick forest to the crashing waves. It is not a very productive place from a gull's point of view, but a surprising amount of life nevertheless exists here. Above reach of the waves and winter ice, lichens, mosses, and crevice plants—three-toothed cinquefoil, hare-bell, and others—add color to the scene, while closer to the forest edge trailing juniper, ninebark, willows, and other shrubs form a denser cover on the rocks. Under and through the plants, a few ants and spiders search for food, and snails make their slow way. It is mid-June, and a tiny chorus frog, hidden in a mossy rain pool, is still calling. New tadpoles lie on the silty bottoms of other pools in the rock.

The gull watches disinterestedly as two myrtle warblers fly from the forest down to the water's edge and begin investigating a stranded log. But when another gull drops from the air toward something floating on the water, she takes off screaming and flies at the other bird, driving it away. She settles on the water and begins pecking rapidly at the prize—a dead sucker. Now other gulls arrive to dispute her ownership. Swooping, crying, splashing, they rip at the fish until one retains it long enough to swallow it. The gulls then fly their separate ways, except for the female, who remains on the water to smooth her ruffled feathers.

Nearby a loon hunts where the gull can't go—beneath the water. Here the shore rocks angle down, full of crevices and indentations where lake chubs, sticklebacks, and other small fish hide. The loon passes these and dives deeper, down to the quieter haunts of lake trout, burbot, cisco, and white sucker. It spots a young burbot, and using its wings for extra speed, churns after the fish. Successful, the loon swallows the fish and returns to the surface for air. When the bird tires, it will abandon the pursuit of fish and hunt snails in the shallower water.

Meanwhile the gull has started a patrol flight down the shore. Briefly it circles over a beaver lodge on the inner side of Smithwick Island, built where it is sheltered from waves. Beavers on these islands are safe from wolves in summer, but their supply of aspen and birch is running low. More and more they are being forced to cut alder, mountain maple, and other less-preferred food. The gull sees no sign of life around the lodge—no frogs, no sunning snakes, no young birds—and flies on.

Goldeneyes nest in tree cavities and take their young to nearby waters to feed. (Photo by R. Janke) |

Gliding over Lorelei Lane, the narrow channel that splits the islands into two parallel strings, she sees families of goldeneyes and mergansers swimming near the shores. Each group of downy hatchling ducks is led by its mother, who dives for fish from time to time but never leaves her young for long. Suddenly the gull notices a little red-breasted merganser that has lagged behind. She swoops quickly, but somehow the mother merganser gets there first, and rising almost out of the water, wards off the gull with beak and wings. The gull continues southwestward down the island chain.

At Mott Island she lands on a little gravel beach, one of many that occur on indentations of the shoreline between rocky stretches. High up the beach, near the fringing alders and fir forest, driftwood and other debris lies in tangled rows, cast up by storms. The gull walks deliberately along these rows, now and then turning over sticks and snatching spiders, beetles, and other small things hiding there. Once she tries for a butterfly that has been attracted to the rotting organic mass. But pickings are thin here too. She takes off and wings strongly toward a place which, in the past, has been rewarding.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Even over the old Rock Harbor Lighthouse, now tilting slightly in disuse, the gull knows food is at hand. She has spotted Pete Edisen, a commercial fisherman here since 1916, out on his dock cleaning fish. Just for fun this time, he has been trolling in Middle Islands Passage and has caught four hefty lake trout. The gull is accustomed to Pete and lands without hesitation on the post at the end of the dock. As he has done for decades, Pete looks up with a smile and tosses the entrails toward the big white bird. Leaving the heads for later, she gulps the entrails whole and with a quiet cry heads toward Burnt Island, near the lighthouse, where her two offspring wait in a shallow nest on the rocks.

Burnt Island, one of many around Isle Royale used by gulls for nesting, is a tall, flat-topped, half-acre rock crowned with a miniature forest of fir, spruce, white-cedar, birch, and aspen. It is the home of song sparrows, foraging beavers, and some 75 pairs of herring gulls. Most of the gulls build their simple, grass- and moss-lined nests in the open at the edge of the trees. Here, beside a low juniper bush, the female and her mate have hatched and raised two light-grey balls of down that now rise on their black legs and with loud peeps greet their mother. Directed by some ancient instinct, they peck at the red spot on her bill until she opens it and regurgitates all she has found this afternoon.

If the food keeps coming day after day, if the weather is not too severe, if they are not killed by a hawk, fox, or another gull, and if they survive three or four winters of southward migration, they may reach adulthood and raise young of their own. But the odds are not good. Perhaps in two or three years the parents will raise four or five young, and perhaps two of these will live to replace their parents. The environment of which the gulls are a part cannot support all that hatch. Nor can it support all the young ducks or all the insects. The gulls are one of many agents that keep these within bounds. As predator, competitor, scavenger, and prey, the herring gull is an important strand in the Isle Royale web of life.

Her young satisfied for now, the female gull flies northward through other circling gulls, on another search.

For the herring gull, Isle Royale's shore zone means food and shelter—in short, home. For man, it means beauty, interest, adventure, a place to fish. This meeting place of land and water has a mysterious attraction for us perhaps greater than that of any other island environment. Let's look at it now, as it gradually changes around the island's rim. We will explore the shore not in gull fashion, but as a boatman would.

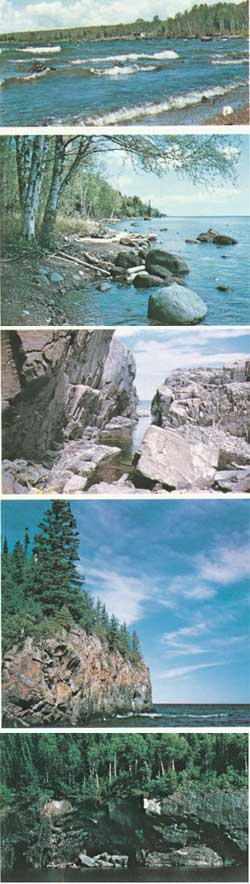

Southwest from Rock Harbor, the basalt humps up steeply from the water, with few gravel beaches for the small boater to land on. Several miles along, a narrow, cliff-walled gap leads into the quiet recesses of Chippewa Harbor.

About two or three miles east of Malone Bay there is a fundamental change in the shoreline, as the surface rock becomes sandstone and conglomerate. Less resistant to the waves than basalt, these rocks make low shores where forest comes down almost to the water. These reddish rocks form the shoreline all the way around to Grace Harbor, at the southwest end of the island.

Malone Bay and Siskiwit Bay, a big scoop out of the island's southern shore, form a distinctive watery environment. Islands, reefs, shallows, deep water, relatively sheltered conditions, and collected nutrients make this area attractive to fish, which in turn attract ducks, loons, herons, gulls, a few otters, and fishermen. This was one of the chief centers of commercial fishing on Isle Royale, and today it is visited by many sport fishermen in search mainly of lake trout. Some of the islands that string out northeastward from Point Houghton, forming the outer edge of the bay, have been used by gulls for years as a nesting ground. Isle Royale Lighthouse stands on Menagerie Island, at the end of the string, to warn ships.

The shorelines of Isle Royale range from treelined gravel beaches to bare rock as illustrated in these scenes from Malone Bay, Siskiwit Bay, Scoville Point, Mott Island, and the north shore. (Photos by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

At the head of Siskiwit Bay are the longest of Isle Royale's rare sand beaches. Made from fragments and grains of red sandstone and conglomerate, these beaches have a reddish color. Moose often follow these shores, leaving deep cloven hoof prints. Occasionally their tracks are paralleled by those of wolves, which use the beach as a regular pathway because of its convenience. In winter, when ice covers the bay, wolf packs often cut straight across the bay from Point Houghton.

From Siskiwit Bay around to Washington Harbor, there is little shelter for the boatman. The prevailing west or southwest wind drives the waves unopposed into the shore. Washington Harbor, with its deep recesses, islands, and nutrient-feeding Washington Creek, forms another oasis of shelter and life at the southwest end of the island. Like Siskiwit Bay, it is another gathering spot for fish, fishermen, ducks, moose, and other creatures. Washington Island, at the mouth of the harbor, has long been a base for commercial fishermen. At the head of Washington Harbor, Washington Creek brings down organic matter and silt, forming a rich, shallow delta where it enters the harbor. Underwater plants grow thickly on this delta, attracting fish and thus ducks, grebes, loons, and herons. The aquatic plants also attract moose, which come at all times of the day and night to feed on them. Sometimes submerging completely, the big bulls come up with water cascading off their wide backs, chewing contentedly on the succulent "salad." In spring rainbow trout and in fall brook trout run up the stream to spawn. A campground and ranger station here at Windigo are fortunately situated for enjoying this focal point of animal life.

Stretching from Washington Harbor to Blake Point, Isle Royale's north shore evokes feelings of adventure, respect, and sometimes fear. When strong northerly winds are blowing, the boatman has few places of refuge along much of this straight, cliff-faced shore. Here the waves are most awesome, beating up against the rock with enough force over the centuries to carve sea caves and arches. Even gulls seem scarcer here, though gulls, herons, and cormorants nest on small offshore islands.

Storm waves batter an islet near the north end of Isle Royale. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

One feels like pausing when he reaches the security of McCargoe Cove, a long, straight cleft angling into the island, created by down-thrusting of the rocks along a fault. At the head of this cove, Chickenbone Creek has formed another delta. The stream now winds through dense alders growing on the stream's deposits. This, too, is a rich spot for animals. Here I have watched beavers, a muskrat, ducks, loons, and moose, and once saw a pigeon hawk trying to catch blackbirds roosting in the alders.

Continuing on our tour we reach the many-fingered northeastern end of Isle Royale, a seemingly endless alternation of long peninsulas and deep, island-dotted coves. Along these sheltered coves, trees grow nearly to the shore. At their heads, mussels abound in the quiet shallow water. This is the land-and-water scene that particularly attracted tourists and cottagers in pre-park days and today is the summer home of most of the remaining cottage lease holders. It is prime canoe country where the portages are short and the possibilities for exploration are long. Several boaters' campgrounds provide good bases from which to enjoy this watery maze.

At Blake Point, the northeastern tip of the island, rough water often makes trouble for boaters. The water between Blake Point and Passage Island, in fact, is considered some of the worst in Lake Superior. Currents are strong and tricky here, and wind compounds the difficulty. The steep, rocky shore offers no shelter. Once around Blake Point, however, we enter Merritt Lane and then Rock Harbor, places of comparative safety.

Such a trip around Isle Royale engenders deep respect for the great lake as well as intimate acquaintance with the herring gull's world.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |