|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

The Red Squirrel: Spruce-Fir Forest

Bird song and the gray light of dawn wake the red squirrel, curled in his grass-lined, leafy nest in an old woodpecker hole. He climbs out, sits on a branch of the dead birch that is his current home, and surveys his domain.

The acre he claims lies on top of a low ridge along the Moose Trail, about one-half mile east of Rock Harbor Lodge. An open, parklike forest of spruce, fir, birch, and a few aspens covers the ridge. Underneath, sapling firs outnumber the young spruces, but nearly all of the firs have been heavily browsed by moose, leaving the upper stems bare of foliage. Large-leaved aster, thimbleberry—with its big, maplelike leaves—wild sarsaparilla, white-flowered Canada dogwood, scattered bluebead lilies, and clumps of low juniper bushes cover most of the ground, but not thickly. Moss grows on rotting logs and stumps. On the north side of the ridge, where the underlying rock tilts steeply down to the shore of Tobin Harbor, moss, other ground plants, and young conifers are thicker, encouraged by the greater moisture. Here old stumps of aspen, cut by beavers years ago, are beginning to rot. On the south side, where the rock slopes gently but faces the sun, the ground cover is scarcer, and includes some reindeer lichens on the rock and patches of bracken fern. At the foot of the slope lies a swamp, draining slowly between this little rise and the next. Here tall spruces cast shade on the grasses, ferns, horsetails, and broad-leaved skunk cabbage that cover the wet ground.

The red squirrel, which feeds on the seeds of conifers, is found in coniferous forests across North America from Nova Scotia to Alaska. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

It is the third week in June. All the summer birds are back and are insistently proclaiming their territories. To the squirrel's ears come the ringing song of an oven-bird, the sweet loud whistle of a white-throated sparrow, the flutelike rising swirl of a Swainson's thrush. Nashville, magnolia, myrtle, blackburnian, and black-throated green warblers add their small but distinctive songs to the early-morning chorus. Down in the swamp, a winter wren unwinds its tinkling medley, and a little yellow-bellied flycatcher quietly whistles, "pun-wee." Intermittently, spring peepers peep.

None of these sounds is important to the squirrel, though they indicate the general locations of nests he might rob. But then a long, chattering "tcher-r-r-r" from down in the swamp electrifies his nerves. "Tcher-r-r-r!" he answers, vibrating with excitement and twitching his tail. It is another squirrel, one of two that occasionally wander up the slope into his territory. He calls again, angrily. Hearing no answer, he starts down the tree to begin the morning's foraging.

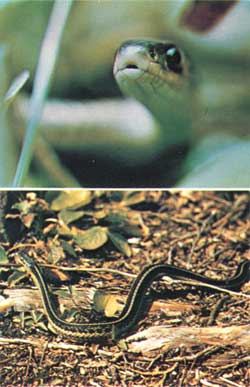

The garter snake (shown here) and the red-bellied snake (not shown) are the only two species of snakes that have become established on Isle Royale. Garter snakes are found in many habitats, including wetlands; the secretive red-bellied snake frequents open woods and sphagnum bogs. (Top photo by Greg Beaumont; bottom photo by Robt. G. Johnsson)) |

Many plants in the forest have something to offer him at one time or another, but now in early summer he is concentrating on the tender buds at the tips of spruce twigs. Stopping briefly on a log to nibble a bracket fungus, he then leaps up onto the trunk of a large spruce and scampers to its top, hardly pausing. For a half hour he carefully examines each branch, crawling out each one until it threatens to drop him. Then, surfeited with buds, he races down the trunk and out a limb, and winds through a succession of tree tops until he is above the top of the north slope. A crunching sound has roused his curiosity, and investigate he must. Below, half hidden in the foliage, a cow moose is stripping the leaves from young birches and noisily chewing them. Behind her, two small, light-brown calves nibble tentatively at ground plants. With the moose population high, most cows have borne only one calf, but these two seem to be thriving. For a week now the calves have followed their mother up and down Scoville Point, sometimes swimming across short stretches of water but seldom leaving the peninsula. Chances are that they will escape wolves this summer, because the pack on the island's northeast end seldom comes near the lodge area during the busy season. Two young bulls, and occasionally a yearling cow, wander through the squirrel's territory from time to time. He chatters at the trio below him, but they pay no attention.

Getting no response here, he works his way through trees and along the ground to a little grove where an aspen stands. Climbing the trunk he reaches a hole just as a downy woodpecker pops into it to feed four noisy young. The squirrel scurries around the hole excitedly, then loses interest and descends to investigate the ground.

Restlessly he bounds along the forest floor, through plants, along logs, then pauses, investigates under an old stump, emerges and continues. He knows every foot of his acre what food it offers, what hiding places for himself and his seed stores, what possible nesting places. He also knows its dangers. A few woodpecker feathers lie scattered near the trail where some hawk or owl has feasted; it might as well have been squirrel fur. An old thigh bone of a hare under a juniper bush wakes an image of a red fox kill he witnessed here the past winter. The fox is a frequent visitor, forcing the squirrel to be ready always to dash for a tree or tunnel. Mink and weasel are occasional threats, but the marten, scourge of red squirrels through much of the north woods, no longer lives on the island. The deer mouse whose territory overlaps the squirrel's is a night animal, subject to attack by weasel, mink, fox, and especially owl. With alertness and luck, the squirrel may live two or three years. The mouse will do well to see another spring.

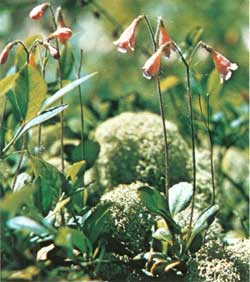

Canada dogwood, a tiny plant related to dogwood trees, grows on the floor of the coniferous forest. |

The squirrel pauses on a log to rest. Near him a bumblebee sprawls on the white bloom of a Canada dogwood. The late morning sun sparkles on the transparent wings of a hovering dragonfly, before it dives at a mosquito dancing in the air. There is an endless supply of mosquitoes; but there are also many birds that catch dragonflies. The dragonfly's chances for lasting the season are much less than those of squirrel or even mouse.

Feeling a certain lassitude in the warm sun, the squirrel climbs up a favorite spruce tree and stretches out on a limb where he can soak up the sun's rays. On the trail beneath him a little red-bellied snake also lies stretched, taking the sun. Like regular second hands of some giant clock, herring gulls fly over on their patrols of Tobin and Rock Harbor, drawing shadows through the dappled forest. Less often, ravens in ones and twos skim the tree tops, croaking as they pass. So familiar are these birds, the squirrel pays no attention. Suddenly a shape comes gliding under the tree tops. The squirrel tenses for flight, but the broad-winged hawk sails past him and lands on a branch over a small grassy pool. For several minutes it sits hunched and still. Then suddenly it drops toward a green frog at the edge of the pool. But at the last moment the frog dives; it will not today feed hatchling hawks a mile or two away on Tallman Island.

Some time later, after the hawk has left, the squirrel resumes his rounds. It is an uneventful afternoon, except for a short chase when he surprises one of the swamp squirrels raiding a food cache. The sun drops toward the ridge behind Tobin Harbor. Sitting beside the Moose Trail, the squirrel feels vibrations. A human family comes by. He runs up a small tree and chatters at them. They stop to look, then walk on. As the sun touches the top of the ridge behind Tobin Harbor, the squirrel starts toward his nest in the dead birch. He has successfully completed another day.

This particular squirrel's patch of forest, though unique like every other patch, has many elements found throughout Isle Royale's spruce-fir stands. The variations in these stands consist mostly in the proportions of the plants and animals common to all of them. The abundance of the constituent plants and animals in turn is determined by the moisture, soil, and sunlight, and by the history of the immediate area—recentness of fire, wind damage, intensity of moose browsing, and other things. All of these factors are strongly influenced by the stand's topography and its location with respect to the Lake Superior shoreline.

The spruce-fir forest grows to the water's edge on Inner Hill Island. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Forests near the shore are the moistest and also most subject to wind damage and moose browsing. The cold waters of Lake Superior cool the adjacent layer of air and contribute moisture to it. This cool, moisture-laden air inhibits evaporation in the shoreline forests, thus allowing most of the moisture in the soil to remain there to be used by plants. A plus factor for tree growth, this is counterbalanced by the effect of wind, which can sweep across the wide expanses of the lake and hit the shore full force, toppling many trees. Shoreline forests also receive the heaviest winter browsing by moose, because these animals find here the greatest quantity of fir, a favorite winter food, and, because of the roof effect of close-packed conifers, somewhat lessened snow depths.

The result near shorelines is a damp forest of small trees with a high proportion of birch, which often springs up in wind-created openings; a high proportion of fir, which would be more numerous without moose; scattered white spruce trees, usually, because of greater resistance to windthrow, taller than the firs; a sprinkling of mountain-ash and white-cedar; and a generally thick, diverse cover of ground plants and shrubs. Old man's beard, a lichen resembling Spanish moss and dependent on high moisture, festoons the trees. Mott and Raspberry Islands have good examples of shoreline forest, though they do not suffer much moose browsing.

Inland and higher up, as the lake influence diminishes, temperatures become higher, thus increasing evaporation. Wind is reduced by the buffering effect of ridges and by the intervening expanse of the forest itself. Oldman's beard disappears. In sheltered valleys, trees can grow fairly tall.

The spruce on the left is unbrowsed; the firs on the right have been heavily browsed. |

One of the most noticeable changes inland is the increase of spruce and decrease of fir. This happens, apparently, because of differences at the surface of the soil. Near the shores decomposition of organic matter is slow on the cool ground. The litter of twigs, needles, and dead plants may become several inches thick. This layer of litter, filled with air spaces, tends to dry out fast after a rain, thus making a poor bed for tree seeds to germinate and grow on. But the roots of fir seedlings grow faster than do those of spruce, and thus are able to reach soil moisture sooner. In the shore zone, more firs survive to become trees. And fir is also more tolerant of shade. Inland, warmer temperatures speed up decomposition, reducing the depth of the litter layer. Also, the drier soil supports fewer trees, which shed less material onto the forest floor. The relative dryness also makes for more frequent and intense fire, which often produces open areas with mineral soil. Spruce is better able than fir to germinate and grow under these conditions and thus is more abundant inland.

The spruce-fir situation illustrates one aspect of the intense competition between plants on the forest floor. In many places, the growth is so thick that tree seedlings of all species can get started only on rotten logs, stumps, or mossy rocks.

The ground cover in spruce-fir forests varies greatly, depending mainly on the amount of moisture and sunlight present. Where conifers stand close to gether, shutting out the sun, the forest floor is nearly bare of plants. Where the canopy is more open, the ground is likely to be covered with mosses, club-mosses, ferns, and a wide variety of herbaceous plants, such as Canada dogwood, wild sarsaparilla, large-leaved aster, star flower, twin flower, wild lily-of-the-valley, blue-bead lily, and fringed polygala. Orchids, though less common, are frequently found; calypso orchid, one-leaf rein orchid, and spotted coralroot are among those forest species seen most often. In northern coniferous forests such as those on Isle Royale, many of the ground plants are evergreen—an adaptation to the short growing season. The wildflowers bloom abundantly through July, unlike those in the deciduous forest farther south, where the majority of flowers blossom in spring before unfurling tree leaves shut off most of the sunlight.

Twinflower grows in the spruce-fir forest along the Mount Franklin Trail. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

The common shrubs include squashberry, red-berried elder, and bush honeysuckle. Where the forest is particularly open and contains much birch and aspen, thimbleberry abounds. This big-leaved plant with the red, raspberry-like fruits has an odd distribution. It occurs around the northern Great Lakes and from the Rocky Mountains northward and westward. Devil's-club, a spiny shrub restricted on Isle Royale to Blake Point, a few islands at Rock Harbor, and Passage Island, has an even more disjunct distribution. It occurs in a few places around Lake Superior, but its principal range is in the Pacific Northwest. The favored explanation for the split distribution of these two species is that in early post-glacial times, when a cool, wet climate stretched all the way across the continent, they had a continuous distribution; when a warmer, drier climate expanded the central grasslands, the area where these plants could grow was cut in two. Climatic change is often a suspected factor when a plant or animal has such an odd range.

The spruce-fir climax forest on the Mount Franklin Trail looked like this in 1964. (Photo by Wm. Dunmire) |

One's walks through these forests of spruce, fir, aspen, and birch are enlivened by encounters with animals. We meet the red squirrel most often; in fact, it seems to be everywhere. Squirrel populations on Isle Royale are higher than on the mainland, although one litter a year, averaging three young, is the rule (compared with two litters averaging more young in other areas). The lack of an efficient predator on squirrels, such as the marten, may be an important reason why Isle Royale's populations are so high. Red squirrels prefer mature forests where conifers abound, though their numbers are also high in sugar maple forests. Conifer seeds and fungi are their staple foods, but they also eat many other things, including seeds, flowers, fruits, and roots of various plants, as well as insects and carrion. Amazingly fewer young are born in poor cone years, though development of the cones occurs after the breeding season. Apparently, the females can detect early signs of cone production and in poor years avoid or inhibit conception.

Early or late in the day you may surprise a snowshoe hare nibbling some plant beside the trail. These animals occur where there is thick cover, such as low-spreading conifer boughs, windfalls, or dense shrubs. The population fluctuations of snowshoe hares are famous, though not well understood. Farther north the cyclic swings are enormous; on Isle Royale these are damped but still quite noticeable. The cycles last about 10 years. Recent peaks on Isle Royale occurred in 1953 and 1963.

The deer mouse is found in almost every state and in all the provinces of Canada. (Photo by Greg Beaumont) |

The deer mouse is the only small rodent on Isle Royale. Of the half dozen or so species of small rodents occurring on the nearby Canadian mainland, this is the only one that has bridged the water gap. Why this and no others is a mystery. Deer mice live throughout the island now but seem to be most abundant in coniferous forests. Individual deer mice, like squirrels, maintain territories. These range from about one-half to one acre in size. The resulting density of deer mice is thus quite low in comparison with that of some other small rodents that occur elsewhere.

The red fox preys on squirrel, hare, and mouse, but hares are its mainstay. So closely is the fox tied to this food source that its numbers fluctuate with those of the hare. Squirrels and mice are relatively unimportant fox food here, since the energy gained from them seldom justifies the energy required to catch them. Occasionally muskrats are caught, but these are too scarce on Isle Royale to provide much food. Birds, too, figure in the diet in a small way, as do frogs, snakes, fish, and insects. Isle Royale's foxes turn their main attention from hares only in late summer, when they gorge on fruits, particularly the dark blue berries of wild sarsaparilla. In winter, they supplement their hare diet with moose meat scavenged at wolf kills. Your chances of seeing foxes are good, since many of them have become accustomed to people at developed areas, and some have become panhandlers and camp robbers.

Like fox, hare, squirrel, and mouse, moose are found over virtually all of Isle Royale. Being dependent on moose, wolves, too, course the whole island. You are quite likely to meet moose, especially around lakes and ponds; but wolves are the island's needle in a haystack. With luck you may hear them howling, and with greater luck catch a glimpse, but for most people they are simply an unseen presence in the forest, adding to it a special dimension of wildness.

In a later chapter we shall look more closely at the lives of moose and wolves. Meanwhile, let's see what is happening in other land and water environments of Isle Royale.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |