|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

The Loon: Inland Lakes

It is noon. The sun shines warmly on the quiet water of Siskiwit Lake, sprawling in its great depression between the Lake Superior shore and Greenstone Ridge. The forest enclosing it stands tall and green on the south side, where aspen and birch have had 75 years to grow since the last fire; and short and green, with openings, on the north side, where the 1936 fire burned clear down the ridge to the lake. At either end, dark swamp conifers stretch back to other, smaller lakes. Circling high above the lake, gulls are moving dots of white.

The common loon, shy of man and preferring wilderness lakes, finds favorable habitat in Isle Royale National Park. (Photo by Frank Singer) |

Out near the middle of Siskiwit Lake, near Ryan Island, a loon dozes, bill tucked under his wing. Just off the shore of the island, his mate shepherds their two light-brown young. Like all young loons, they had taken to the water the day they hatched, but they still depend on their parents for food.

Having rested enough, the male wakes up and dives. Soon after submerging, he spies whitefish and ciscos; they are too far away to be overtaken. He continues down, into the dim world a hundred feet beneath the surface. Here, just above the fine brown mud covering the bottom rock, he comes upon a lake trout. But it is too big. He angles up toward the light. On his way, a school of young ciscos flashes by. He spurts after them and catches one that lags. Continuing underwater, he swims to his family and breaks the surface with his prize. He mashes the cisco in his bill and passes it to his mate, who feeds it to one of the young.

As the male swims slowly away, six loons down the lake begin yodeling. Two pairs and two unmated birds have joined in a tight flock on the water and now circle around, calling crazily. The male, a mile away, wails in answer. With feet spattering and stiff wing-tips hitting the surface, he makes a long take-off, then arcs over the middle of the lake, where the other loons have congregated. But the instinct to feed his family is stronger than the social pull of his brethren. He turns and flies to the east end of the lake.

Here the rock bottom slopes up and stream deposits lie in quiet coves along the shore, making shallow water where aquatic plants can grow, small fish can thrive, and snails, mussels, and leeches can find food. Among the many little islands, female mergansers and goldeneyes lead their broods. Along the shore, teetering spotted sandpipers search for insects. Crowding down almost to the water, green alders, ninebark, sweet gale, and white cedar make a dense shoreline fringe.

The loon finds good feeding here in the shallows. Much of the afternoon he flies back and forth from these quiet coves to his family with offerings of snails, leeches, and small fish. A mink hunts here too, leaving empty mussel shells strewn along the shore. Among the horsetails, burreeds, spikerush, and yellow pond lilies, great long pike pursue smaller fish, seizing them in their saw-toothed jaws and gulping them into their cavernous mouths.

The hours pass. The sun turns red and sinks below Greenstone Ridge. Up in the young birches on the north side of the lake, a hermit thrush salutes the evening with liquid, ethereal song. In a small cove behind a rocky peninsula, beavers emerge from their lodge and make V's through the water, intent on foraging. Two bats flutter erratically over the lake, catching insects. Off toward Wood Lake, a loon utters a long, gull-like cry, sending echoes ricocheting across the water. Then, as if set off by this sound, a pack of wolves somewhere on the south shore begins howling. Punctuated by yips and barks, the voices rise and fall, saying something that needs to be said.

The male loon patters across the water, lifts into the air, and disappears slowly toward Siskiwit Bay, his stiff wings "putt-putting" like some distant outboard.

In some ways, Siskiwit Lake mirrors all the lakes of Isle Royale. It has the cold-water fish of the few deep lakes, and at its shallow ends it has much of the plant and animal life typical of the smaller, shallower lakes.

Of Isle Royale's 42 named lakes, four are oligotrophic; that is, they are cold, deep, and clear, and are poorly provided with nutrients. In addition to Siskiwit, they are Desor, Sargent, and Richie. The first three have one or more forms of the cisco-whitefish group; Richie does not. Siskiwit Lake also has the cold-water lake trout, which fishermen pursue in summer by bumping baits along the bottom. These lakes, because of their low levels of nutrients, support only small numbers of plankton (microscopic plants and animals). The rocky bottoms are too deep for much sunlight to reach them, and most of the shore is unprotected from wave action; thus there are few places favorable to rooted aquatic plants. But on Siskiwit there are always a few sheltered spots that meet their requirements.

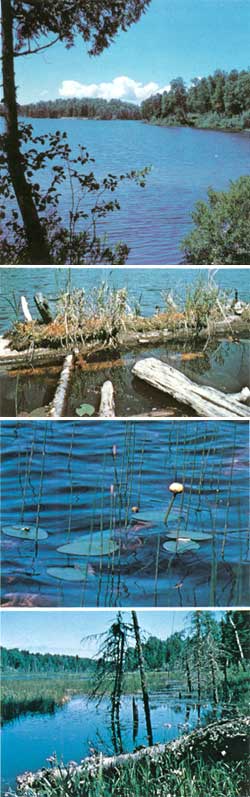

Lake Richie (top), one of very few oligotrophic lakes in the park, is characterized by comparatively great depth and clarity and a poor supply of nutrients. About half of Isle Royale's lakes are eutrophic, like Forbes (above and top right). They support many kinds of plants, such as the insectivorous sundew growing on a log and the rooted cow lilies. Dystrophic lakes such as Moose (right) tend to be boggy and low in fish productivity. (Photos by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

All the island's other lakes are classed as eutrophic or dystrophic. They are characterized by shallow, warm water colored by organic matter and tannic acid; high nutrient levels; and abundant plankton and rooted aquatics. In these lakes, the balance is being tipped in favor of plant over animal life. Among the many plants which take root on the bottom and send shoots above the surface or below it are spikerush, burreed, yellow pond lily, horsetail, northern naiad, cattail, and various kinds of pondweed.

With less diversity of habitats present, there are fewer species of fish in shallow lakes than in the deeper lakes. The dominant predatory fish are northern pike and yellow perch. White sucker, blacknose and golden shiner, and brook stickle-back are common plant-feeders. The redbelly dace, finescale dace, and fathead minnow are particularly typical of some of the shallower, more stagnant lakes, such as Lily, Wallace, and Sumner.

In the shallow, quiet water near lake shores you are also likely to find snails, mussels, and those friendless creatures, leeches, of which Isle Royale has about 15 species. Snails feed on algae growing on rocks. Mussels burrow part way into the sand or mud and siphon water, ingesting the copepods and other minute animals in it and pumping out the rest. Most leeches eat small animal life, such as insects up to about 1/4 inch. Some species attach themselves to animals, including humans, and suck blood—which is why swimming in the inland lakes is not recommended. One very small species fastens onto the gills of fish. Along the shore of any lake you are apt to surprise green frogs, the island's commonest amphibian.

Several kinds of mammals and many birds that feed on aquatic life are found around the inland lakes. Moose are especially fond of aquatic plants, and beavers like them too. Mink restlessly search out frogs, snakes, fish, birds, and other small animals, while their larger, scarcer cousin the otter feeds chiefly on fish, pursuing them with marvelous, fluid speed. Muskrats, also scarce on the island, feed mainly on plants, but also eat mussels, other small aquatic animals, and carrion. On the larger lakes, red-breasted and common mergansers dive for fish, while goldeneye ducks may be found on almost any lake or beaver pond. Gulls keep an eye on all water bodies, and loons, which need a long run to lift their heavy bodies into the air, visit any lake with adequate take-off space.

Along shores, great blue herons stalk fish and other aquatic animals, spotted sandpipers hunt at the water's edge, and kingfishers dive for small fish from overhanging branches or from the air. Occasionally, ospreys may be seen at inland lakes, where from high in the air they plunge into the water for fish.

An open bog in the 1936 burn area and the bog on Raspberry Island represent early and late stages in succession. (Top photo by Wm. Dunmire; bottom photo by Robt. G. Johnsson)) |

Sadly, ospreys and bald eagles are disappearing from the island scene. They were once common here, but chemical pesticides that have been absorbed by fish, the principal food of these birds, have decimated both species. Lake Superior is not yet highly contaminated; the poison is probably mostly ingested farther south in winter. Ospreys and eagles build their big stick nests high up in trees, ospreys choosing dead trees while eagles use live ones. Some of the abandoned nests remain for years, slowly disintegrating.

Three of Isle Royale's lakes have witnessed the evolution of new species or subspecies. Siskiwit Lake, although only 50 feet higher than Lake Superior, has been separated from it for about 5,000 years. In this time, through small mutations and differential survival, the ciscos in Siskiwit Lake have changed enough to be considered a new species. In Sargent Lake, about 100 feet above Lake Superior, a subspecies, the Sargent Lake cisco, has evolved. Lake Desor can make sole claim to two subspecies: the Lake Desor cisco and the Lake Desor whitefish. And Lake Harvey has three—a pearl dace, a blacknose shiner, and a fathead minnow—all bearing its name. In the case of each lake, isolation from Lake Superior and other inland lakes on the island prevented the intermixing of populations that would have kept them genetically uniform. Why all the species in these three lakes did not develop into new forms will probably remain one of the mysteries of evolution.

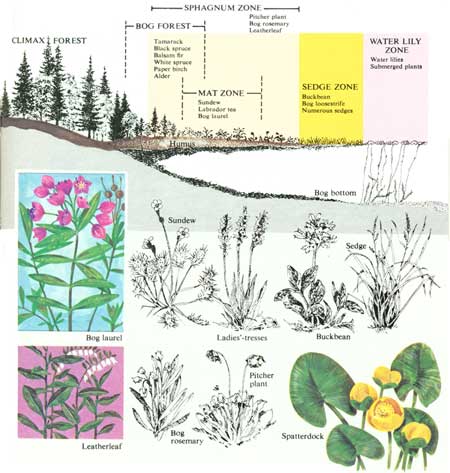

For all their specialized forms of life and apparent permanence, lakes are nevertheless one of the more ephemeral features of nature. They die partly through the downcutting of their outlets, which lowers the surface of the lake; but the chief agents of death are siltation and spreading plants. Wherever the water is shallow and quiet, aquatic plants take root. On the shallower lakes, a floating mat of vegetation may develop and eventually cover the surface. Water lilies, spikerushes, and others we have mentioned begin the process. As the vegetation becomes denser, trapping more and more silt and organic debris, sedges begin to form a mat on the surface. Gradually this sedge mat extends farther and farther out over the water, as dead plants and roots help to fill in the space underneath. As the shoreward parts of the mat fill in and become somewhat drier, sphagnum moss often begins growing on it. Whether sphagnum appears or not, shrubs soon become established; leatherleaf, bog rosemary, and alders are the most common. Where sphagnum is present, Labrador tea usually takes root, eventually choking out the other small shrubs and much of the sphagnum as well.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As the sedge mat continues to grow out over the lake, succession progresses on the landward parts. Debris from the plants helps to build soil, and certain trees become established. Where the soil is slightly acid, black spruce becomes the dominant species. Where it is slightly alkaline, white-cedar is more prevalent. Sometimes a few tamaracks also grow in these bog forests.

Eventually, as the soil builds and dries, the "climax" species become established. Since most lakes and bogs on Isle Royale are at the lower elevations, these species usually will be white spruce and balsam fir. When this stage is reached, all influence of the former lake is gone. It is truly dead.

The osprey, whose survival has been threatened by environmental pollution, adds a note of excitement to the Isle Royale scene. This nest, like most osprey nests on the island, was built in the top of a tree killed in the 1936 burn. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

On Isle Royale you can see all phases of lake extinction. Hidden Lake, for instance, at the start of the Lookout Louise Trail, has an irregular fringe of bog mat. Lily Lake, in the southwest part of the island, is closed over with a classic floating mat. Walking on it you can feel it spring up and down. Growing on the spongy surface are specialized plants such as sundew, pitcher plant, and certain orchids such as rose pink and ladies' tresses. At Raspberry Bog, on Raspberry Island, the mat has closed completely. A boardwalk nature trail here takes you through successive zones—from black spruce to Labrador tea to leatherleaf—that represent phases in formation of the bog. And looking down from almost any ridge, you can see dark conifer swamps. Some of these may stand in place of former lakes. You are witness to yet another aspect of change on ever changing Isle Royale.

Some lakes, however, will resist a very long time. The larger and deeper a lake, the longer it will take to fill. Depth is an obvious deterrent, but large surface size slows the filling process in less obvious ways. Over lakes such as Siskiwit, Desor, and Feldtmann, the wind sweeps unobstructed, building up large waves. These discourage establishment of aquatic vegetation. And during warm spells in winter, the ice cover expands, pushing out over the shore and bulldozing anything in its way.

Ten thousand years from now—to be optimistic in more than one way—our descendants may still hear loons wailing on the broad waters of Siskiwit Lake.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |