|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

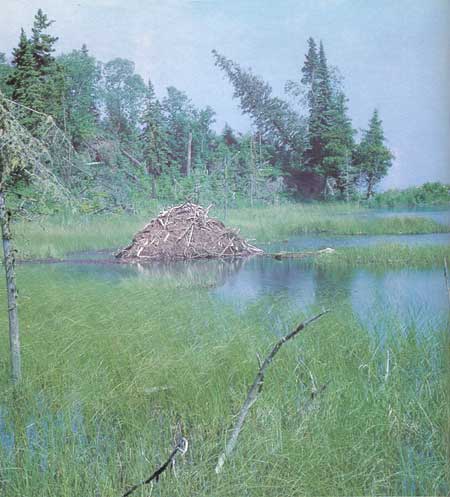

The Beaver: Ponds And Streams

The trail crew doesn't know it, but they have helped the beavers. Alongside the trail leading into Chippewa Harbor the beavers have created ponds. Some of the aspens they cut fell across the trail, and the trail crew has had to saw off the blocking trunks and branches. This has saved the beavers a lot of work. Now they are simply dragging the branches to their pond and consuming the tender parts. Floating in the water near shore, each beaver takes the small end of a branch in its front paws and feeds it into its mouth. "Crunch, crunch, crunch"—several leaves and a few inches of stem disappear. More quietly the beaver then chews this mouthful to a pulp and swallows it. "Crunch, crunch, crunch"—the next piece gets processed.

(Photo by R. Janke)

This beaver family—father, and mother with last year's and this year's young—indeed have been living amidst plenty. In the past few years they have worked down along a small stream, building a succession of ponds between two low rocky ridges crowned with jack pine. Their current lodge is the middle of the last pond, secure from invasion. From this lodge they can travel up through their six ponds, now in summer harvesting mostly herbaceous plants and thimblebernies on shore, and in spring and fall any of the numerous aspens and birches that grow in the surrounding forest. Up to a point, that is, for the farther they venture from the water the more vulnerable they become—each foot of distance from the safety of the pond increases the chance that a wandering wolf might catch them. Thus far, with plenty of trees left, they have cut no farther than a hundred feet from shore. At the head of the uppermost pond, however, they have dug a channel 150 feet long to allow them to reach some particularly big aspens.

(Photo by R. Janke) |

With many aspens—their favorite food—and many birches around, the beavers have been wasteful. Inevitably, some of the cut trees lodged against their neighbors, but even on trees that fell to the ground, many accessible branches have not been used. The beavers cannot afford this profligacy for very long, because they have reached the dammable limits of the stream. It trickles through their lowermost dam, across the trail, and down a steep hillside. Upstream from their six active ponds, they or their ancestors have already exploited the forest, leaving a series of old grassy ponds and wet meadows. Some birches but few aspens remain in those areas.

As the beavers chew aspen branches this rainy afternoon in late July, other creatures are also using the pond the beavers have made. Like knots on old logs that lie in the water, grey-brown goldeneyes and hooded mergansers sit motionless. Now half-grown, they have known no other world than these ponds, criss-crossed with fallen trees and the white reflections of still-standing birches killed by the water. On other logs, painted turtles rest like stones. In the leaf-filled shallows along shore, green frogs, too, sit still. But some creatures, like the beavers, are on the move. Garter snakes crawl slowly along the pond edge, hunting frogs. A muskrat swims away with some of the beavers' aspen twigs. A solitary sandpiper, resting at the pond in its late-summer migration south, flutters up with a sharp "peet-weet!" as the muskrat passes. Between the two rock ridges flanking the ponds fly birds of the forest—blue jays, gray jays, woodpeckers, chickadees. The pond is indeed a focus of life.

As afternoon becomes evening, a cow moose wanders over the ridge with her calf. From the opposite direction—up the hill from Chippewa Harbor—comes a spike-horn bull, his one-pronged little antlers fuzzy with velvet. He sloshes through the upper ponds, being careful to avoid the cow. But now all the moose freeze. They have heard a deep bark from down on the trail to Lake Mason. Silently they melt back into the forest. A few minutes later the gray forms of wolves appear at the pond's edge. They sniff along and they listen for the sound of a beaver chewing. But all the beavers are in the pond. The wolves lap at the water, then trot up the trail toward Lake Richie. Their hunt has just begun. Slowly, pausing often to test the air, the parent beavers swim toward shore to begin the night's harvest.

On Isle Royale, wherever there is water deep enough to dive in, or a trickle that can be dammed, there are likely to be beavers. They inhabit protected Lake Superior shorelines, most inland lakes, and a multitude of ponds of their own making. As of October 1969, an estimated 750 to 1,000 beavers lived on the island, concentrated mainly on the lake-dotted northeast half. Historically, this is a high number. In the 1940's and 1950's numbers were much lower, presumably because of an epizootic disease such as tularemia. In the 19th century, as we have seen, beavers were gone, or nearly so.

The greater yellowlegs is one of many wild animals that benefit from the engineering activities of beavers on Isle Royale. These ponds were established by beavers on Indian Portage Creek, near Chickenbone Lake. (Top photo by Greg Beaumont; bottom photo by Robt. G. Johnsson)) |

No other animal, including the moose, has as much ecological impact on Isle Royale as the beaver. For this big rodent creates a new environment wherever it goes. When beavers enter virgin territory to build a dam (which still happens on Isle Royale, though old, regrown pond sites are usually available), they kill a section of forest by flooding. This drives out terrestrial animals and most of those inhabiting the trees. Around the shores of the ponds they open the forest further by cutting shrubs and trees, particularly aspen and birch.

While the beavers are destroying forest habitat, to the detriment of some animals, they are creating new habitat for others. The habitat for such quiet-water fish as white suckers, brook sticklebacks, golden shiners, and blacknose shiners is greatly expanded. Frogs and painted turtles find new territory, while frog-hunters such as garter snakes and minks are given new hunting grounds.

Beaver ponds, in fact, afford some of the best wildlife watching on the island. Creep up to any pond, sit quietly, and you are bound to see something interesting. Maybe it will be a moose, come for aquatic plants. Perhaps you will see the makers of the pond themselves, eating, grooming, or working on their dam or lodge. And always there will be birds about. If you have arrived stealthily, you may get good looks at mallards, black ducks, teal, goldeneyes, hooded mergansers, or ring-necked ducks. In the first half of summer there will probably be tree swallows, coming and going from their woodpecker-hole nests in dead trees. A kingfisher or great blue heron might be fishing there. Watch for cedar waxwings, kingbirds, or olive-sided fly-catchers snatching insects from the air over the pond. And listen for song sparrows and swamp sparrows singing from the marshy fringes.

Each beaver pond is different, not only in its activity at any given moment, but also in its situation and appearance. If the valley is deep and narrow, the pond will be deep and narrow, as in the case of the ponds described near Chippewa Harbor. If the valley is broad, with gentle slopes, the pond will be shallow, with much vegetation in it. If the pond is fairly new, it will probably have many dead trees or even some live ones standing in it; older ponds will be more open. A new pond created at an old pond site, where a meadow has developed, may be dotted with islands of grass and sedge. Some ponds are large; others are small. On a tiny rivulet I saw one that was five feet wide and eight feet long—a useless monument to the beaver's eternal dam-building urge.

When a beaver colony exhausts the food supply at its pond, it moves to a new site, allowing a reclamation process to begin at the old one. Without attention, breaks in the dam allow the pond to drain, leaving a bare, muddy surface. This is soon invaded by annuals and short-lived perennials, such as touch-me-nots, loosestrife, Joe-Pye-weed, raspberry, sedges, and rushes. These gradually give way to bluejoint grass, which covers not only the old pond bottom, but also the remains of the dam and lodge. Very slowly, speckled alder extends its control from the edges toward the center. In these early stages of succession, red-winged blackbirds, swamp and song sparrows, and short-billed marsh wrens are given new nesting areas. After many years, if another beaver colony does not occupy the site, the surrounding forest may succeed in reclaiming its former territory. This last phase is exceedingly slow, however, because the dense cover of grass and shrubs, as well as adverse chemical conditions in the soil, discourages tree establishment. Thus, beavers may be viewed as agents of diversification, working against the forest's trend toward uniformity.

The Canada goose is seen during spring and fall migrations. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) The painted turtle is one of many animals benefiting from the activities of the beaver. (Photo by T. Haas) |

Of all the beaver's relationships with other animals, perhaps most important ecologically are those with the moose; and the moose gets much the better of it. The ponds provide moose with aquatic plants, which contain minerals they can't get elsewhere. But each bite taken by moose means several less for beavers, which also like aquatic plants. By cutting aspens and birches, beavers provide moose with tree-top foliage and bark they could not otherwise reach and with root sprouts sent up by the cut trees. So intense is the browsing, and so great is the competition from shrubs and conifers, that most of the resprouting aspens are killed, thus depriving beavers of a new supply of their primary food source.

The streams of Isle Royale, which offer beavers so many possibilities for ponds, constitute in themselves yet another type of environment. Sluggish streams, particularly those flowing through meadows or marshes, have much the same kinds of life, though less of it, that beaver ponds have. The more rapid streams harbor sculpins, white suckers, long-nose dace, and sometimes brook or rainbow trout. Washington and Grace Creeks have both resident and spawning trout. The Little Siskiwit River is also known for its brook trout. In the spring, thousands of white suckers and smelt run up many streams to spawn.

Touch-me-not, or jewel weed, grows along the borders of streams and in other wet soils. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Most of the water draining off Isle Royale first flows quickly in little brooks down ridge slopes, then turns sluggish as it reaches valleys and drains through swamps and beaver ponds toward Lake Superior. Waterfalls are few, those on the Little Siskiwit River and Siskiwit Lake outlet being among the better known ones.

Oddly enough, at the mouths of some Isle Royale streams that empty into long harbors or bays, the flow alternates between downstream and upstream. In most of these cases, the flow shifts direction every 10 to 30 minutes. This phenomenon is not well understood, but it is not tidal. It is thought to be caused by the periodic building up and release of water at the heads of the harbors. Wind, if it is blowing up-harbor, and stream discharge cause the water to build up. Periodically, the build-up becomes great enough to cause a down-harbor shift, thus allowing the stream to flow in its normal direction. Washington and Tobin Creeks and the Big Siskiwit River exhibit this phenomenon quite markedly. Over Lake Superior as a whole, differences in atmospheric pressure cause similar, though less regular, effects. Such oscillating waves, known as seiches, occur in many lakes, bays and gulfs of the world.

As we have seen, the watery lowlands of Isle Royale provide for the needs of many forms of life. Let's climb now to a very different sort of place, where heat, dryness, wind, and lack of trees call for different strategies by other kinds of creatures.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |