|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

Departure

All too soon our visit ends. We must board the boat or plane and return to our mainland life. But though we leave the island, the island does not leave us. For we carry away memories: of a bull moose feeding in an evening lake, of fog rising from a wild rock shore, of night talk around a warm fire. And perhaps we try to put it all together—to see what the island has meant to us.

For some, the scientist particularly, the island has meant a chance to study nature in a place where man intrudes but little, and isolation produces a unique ecological laboratory, a nearly closed system.

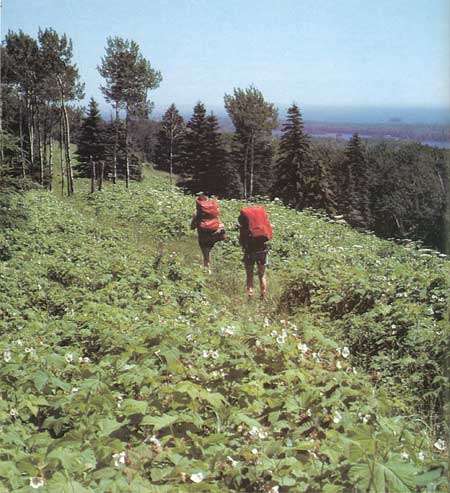

(Photo by Rolf O. Peterson)

For most people, the island has meant a brief experience of wilderness—a glimpse of the primordial world and of oneself as a human animal in it. The wilderness value of Isle Royale calls, I think, for some discussion, because it is a fragile thing requiring careful protection. More than to any other national park, people go to Isle Royale primarily for a wilderness experience. Yet, embracing 200 square miles of land and water, it is a small place as national parks go. As more people come to enjoy its wilderness, each person's wilderness experience is diminished, since solitude is its central ingredient. Clearly, there are limits beyond which visitation must not go. What those limits should be, how they should be achieved, and how much freedom visitors should be allowed once they get to the park are questions the Park Service wrestles with and with which all Americans—the "owners" of Isle Royale—should be concerned. In both a psychological and an ecological sense, Isle Royale has a limited carrying capacity for people as well as for wildlife.

Stuart Perry, editor of the Adrian, Michigan, Daily Telegram, foresaw the problem in 1931, when he wrote, "[Isle Royale's] value lies in its solitude and primeval condition rather than in any natural wonders. If there were natural wonders, it might be the duty of the public to make them as accessible as possible, but in the circumstances I maintain that the duty of the park management should be to make the place as inaccessible as possible in order that its peculiar value and charm may be conserved." To some extent, this painful remedy will have to be applied.

Another important part of the Isle Royale experience is the opportunity it gives us to be human. In this basic situation, we learn again the simple joys of eating after hunger, getting warm after being cold, drying out after being soaked, or resting after a long day's hike. And we learn again the value of the individual. With pressures removed, fewer people around, and a dependence on those few in case of emergency, we recognize our need for each other and have the chance to know each other simply as unique human beings. The common experience of all these things creates a special fellowship.

Finally, living on Isle Royale even briefly gives us a rare chance to gain perspective on ourselves and our civilization. Somehow the remoteness and the difference of this place wipe out our old images and allow new ones to form against the simple, natural background around us.

And so we return to our man-made world, shocked by its concrete and cars, but knowing that the island remains—a contrast, a restorer, a measure of our civilization.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |