|

Volume XXIV - 1993

Where Have the Whitebark Pines Gone?

By Steve Mark and Ron Mastrogiuseppe

Even a cursory glance at the landscape reveals that vegetation is

not distributed at random, but occurs in mosaics as an expression of

several interacting variables. The whitebark pine (Pinus

albicaulis, meaning white-stemmed pine) is a tree found at Crater

Lake National Park generally above 6500 feet on exposed slopes in dry,

rocky soils. This tree is easily identified by its whitish-gray bark and

often twisted branches. Although Crater Lake National Park has no true

timberline, whitebark pine forms the elfinwood or krummholz of

timberline in many western mountain ranges.

Whitebark pine is a pioneer species colonizing subalpine habitats as

the first tree. An amazing example of its pioneering ability can be seen

at the Newberry caldera where whitebark pine is the only tree

established upon the relatively recent obsidian surface; even the nearby

lodgepole pines (P. contorta, subsp. murrayana) abruptly end near

the toe of the flow. At the Crater Lake caldera, whitebark pine may have

been the first tree to colonize the pumice slopes of old Mount Mazama

within the first century following the climactic eruption. Whitebark

pine is generally encountered as a pioneer tree, as there are several

places around the caldera rim where old mothertrees provided a favorable

microclimate for the establishment beneath their canopy of subalpine fir

(Abies lasiocarpa) or mountain hemlock (Tsuga

mertensiana). Whitebark pine is arranged in ribbons or bands along

the contours of Cloudcap and other habitats along the caldera's edge.

These sites represent slightly higher, rocky substrate for the survival

of whitebark seedlings since exposed areas devoid of snow earlier in the

year have a significantly longer growing season.

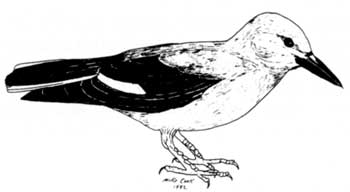

Most pine seeds have wings for wind dispersal, but whitebark seeds

have retained only a rudimentary wing. The dispersal agent has become

the Clark's Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana). These birds have

learned to retrieve whitebark seeds with their specialized beaks,

storinga number in their sublingual pouch, and methodically storing

seeds in soil caches. Only a fraction of the seed caches are retrieved,

however, so some caches sprout seedlings in clumps which may grow into

larger whitebark pine colonies.

Whitebark pine appears to be sensitive to a certain set of

environmental conditions. Although it is often viewed only as an

indicator of a short "rowing season and cold temperatures, this species

occupies a niche in the subalpine forest that is far from simple. The

tree can be found in relatively pure stands or in association with

lodgepole pine and western white pine (P. monticola). The

distribution of related species like limber pine (P.flexilis),

bristlecone pine (P. longaeva), and foxtail pine (P.

balfouriana) somewhat overlap that of the whitebark and can occupy

what would often seem to be the latter's place forming the edge of

timberline. Whitebark pine's distribution poses some nagging questions

to dendrologists. For example, it provides the name for Nevada's Pine

Forest Range but mysteriously remains absent in similar subalpine

habitats on Steens Mountain in southeastern Oregon, only several air

miles to the north. In southern Oregon, the whitebark pine may have

disappeared on Mount Ashland in recent times and is presently almost

gone from the top of Crater Lake's Wizard Island.

One of the reasons that whitebark and other pines are often so

puzzling is that species of Pinus display much variation as well as many

similarities. For example, whitebark pine and limber pine (the rarest

native coniferous species in Oregon, but more common in the Great Basin

and northern Rockies) mimic each other in many characters. Similarly,

the ponderosa pine (P.) found along Annie and Sun creeks, for

instance, display a strong Washoe pine (P. washoensis) element.

This is thought to be a high elevation variant of the ponderosa's

northwestern distribution and may account for its presence at higher

elevations inside the caldera. Genetic variability in the park's

whitebark pine may not be as great as in the ponderosa forests, but the

loss of a population as small as the one on Wizard Island may imperil a

distinct local seed source.

What is disturbing about the whitebark pine of Wizard Island is

their seemingly rapid decline. Photographs taken at various times

through the 1960s show living trees on top of the island. By July 1991,

however, the authors could find only one living specimen. This small

population's relatively sudden nosedive may be due to one or several

causes. Might it be human activity, air pollution, drought, mountain

pine beetle, or blister rust infection? The whitebark's decline is more

likely tied to a combination of these factors, which makes the testing

of single hypotheses (a key to the application of scientific method to

the problem) very difficult or, at best, inconclusive.

Efforts aimed at monitoring environmental change in national parks

like Crater Lake are generally handicapped by the lack of critical

baseline information. Material available to the historian may help to

reconstruct past conditions, but investigators should be aware of their

possible shortcomings. The documentary record is limited to the historic

period, whether it is in the form of photographs or writings.v

Repeat photography is constrained by the scale and resolution of the

original photo, as well as by the identifiable background features that

allow a view to be replicated. Observations about the condition of

flora throughout the park are usually fragmentary. Some describe what

would seem to be unlikely events, even though the journalist may

otherwise be credible. One example is a newspaper article of 1903 where

Klamath Falls hotelier and photographer Maud Baldwin noted that Wizard

Island was '"alive with grasshoppers. " Sufficient detail or locality

data to verify an observation can be a problem, too. Much effort was

expended by Crater Lake's chief park naturalist in the 1960s trying to

track clown a colleague's discovery of the prostrate juniper

(Juniperus communis) specimen probably living near the Watchman

in 1929.

Other changes that might have occurred during the historic period

lack any form of documentation. Just one of many examples in the park is

the poor condition of Sun Meadow's vegetation when compared to the

floral mosaic of Sun Notch. Simplistic explanations, such as sheep

grazing prior to the park's establishment or a poor soil nutrient

budget, are often offered by park staff when the limitations of

available evidence or funding seem to frustrate efforts to study the

situation further.

What the whitebark's disappearance on Wizard Island may illustrate,

as have the attempts to understand fluctuations in Crater Lake's

clarity, is that we really under stand very little about the park's

ecosystems. Certainly more research is essential, but the limitations of

available data have to be accepted since causation may be due to a

number of factors not easily separable into testable hypotheses. Instead

of certainty, all history and science can yield is a prediction of

possibilities if the limitations affecting available evidence can be

overcome through sound methodology.

Explanations based on models of complexity rather than simplicity

will have to be complemented, however, by a willingness to admit that

sometimes we do not have all the answers. Since whitebark pine ring the

summit crater which provides the lake's name, what better symbol of

uncertainty could there be for a phenomenon as complex as Crater

Lake?

|