|

Volume XXVI - 1995

Fire as an Agent of Change

By Doug Lowthian

In 1994, Crater Lake National Park experienced 44 forest fires.

These fires occurred throughout the park, from the Boundary Springs area

to Sharp Peak and Annie Creek. Contrary to the widely held belief that

fire in the forest is devastating and destructive, the fires at Crater

Lake were beneficial products of a natural process eons old.

The vast majority of these fires during the 1994 fire season were

under one tenth of an acre. A few grew to an acre or two, but less than

five surpassed ten acres. One event, known as the Agee fire, was

particularly interesting. This fire took nearly a week to find as the

lookouts kept losing sight of the furtive smoke. Rugged topography south

of the lookouts at Watchman and Mount Scott prevented a clear

pinpointing of the smoke. It would pop up in the afternoon for a short

time and then disappear, laying down in the tree canopy. When the smoke

could be seen, it seemed to be on the southwest flank of Crater

Peak.

A team of two firefighters were sent to locate the source of the

elusive smoke. After four hours of climbing up and down the steep

slopes, pushing through thick stands of snowbrush, Ceanothus

velutinus, and sliding down scree, they stopped for lunch. In

casually scanning the northern skyline, they saw something that made the

drop their sandwiches and pick up their binoculars. They found the

smoke, but it was not on Crater Peak. Although in line with the lookout

tower on Watchman, the fire was on a ridge above the East Fork Annie

Creek--over a mile and a half away! Since a deep canyon lay between them

and the fire, they ate while hiking out. This turned into a near run so

that they could get back to East Rim Drive and revealed itself, less

than one and a half mile from headquarters. In an ironic twist, this

fire turned out to be one of the closest to home.

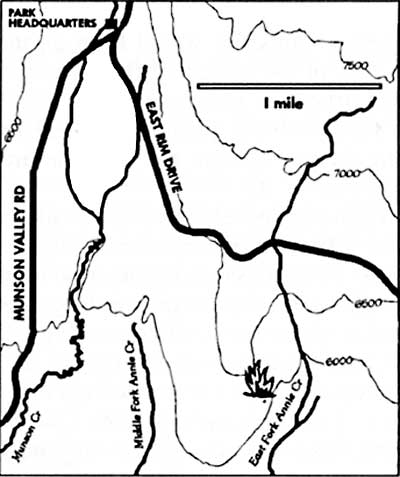

Locating this fire on the park map is easy. Place your finger at

Park Headquarters and follow East Rim Drive until it crosses the east

fork of Annie Creek. Turn south and go about three quarters of a mile.

On the west side of the creek, a steep slope runs up from the canyon

bottom to the 6,000 foot level. You will see a ridge dividing the middle

and east forks of Annie Creek. Along this ridge the fire burned slow but

steady through a mature forest consisting of Mountain hemlock. Tsuga

mertensiana, and Shasta red fir Abies magnifica-procera. Upon

discovery, the fire covered less than half an acre. The decomposing

layer of needles and twigs smoldered and smoked heavily. Occasionally

the crackling of burning live needles broke the quiet. Small seedlings,

with their branches near the ground, were torching. This sent flames up

as high as three or four feet, dying out as quick as they started.

Map by Susan Marvin.

There have been fires around what is now Crater Lake National Park

for many thousands of years. Chances are, however, that what became

known as the Agee Fire was the first in this part of the forest for

quite some time. Far from being static and seniscent, the forest is

constantly changing. Agents of change such as wind, precipitation, and

fire alter species composition and stand density in the forest. These

processes occur with varying frequency, depending on the type of forest.

The frequency of fire in a given locale can be averaged to obtain its

Fire Return Interval. This number can vary greatly throughout a forested

area depending on the species makeup, altitude, aspect, topography, and

prevailing weather patterns.

The forest where the Agee fire burned has a mean fire return

interval of approximately 40 to 50 years. This means that the fire was

burning on land that probably had not burned in the last 50 years or

more. The variability among fire return intervals is usually very broad.

For example, one researcher may find evidence of fires within the last

decade, while another might find that a similar area had not burned for

120 years. The accuracy of these numbers usually depends on the extent

of the survey.

The Agee fire burned for about eight weeks before being extinguished

by snowfall in early November. During this time, firefighters made

efforts to contain the fire within a fixed perimeter. With many other

fires burning throughout the park at the same time, people and equipment

were stretched thin. The weather remained hot and dry for several weeks

after the fire started. Temperatures in the 80's and humidity as low as

13 percent pointed to conditions normally associated with high fire

danger. For the most part, however, the fire burned slowly through the

underbrush and duff layer.

To study the effects this fire would have on the forest, plots were

established in the path of the spreading flames to measure various

components of the stand structure. These plots quantified the amount of

burnable material, or fuel, and the quantity and density of live trees

and shrubs. By reading the plots before and after the fire the change

caused by the fire could be measured.

The results of these measurements point to the fact that fire is

rarely a devastating event. Even the massive fires at Yellowstone in

1988 were agents of change that led to massive regeneration of the

forest. The Agee fire, burning through a period of high fire danger,

altered the forest in ways that were not as dramatic as all-consuming

fire storms. This fire killed just 13 percent of the trees over ten feet

tall, and only 41 percent of the trees under ten feet tall. The fire

thinned out the young trees, providing better conditions for the growth

of those that remained. What few large trees that were killed now allow

for more sunlight to reach the forest floor where grasses and shrubs

will sprout next year. During the fire many signs of elk were present an

should be again once the forage returns. The large dead trees will also

provide valuable habitat for birds, bats and insects. In topping out at

30 acres, the Agee fire left a forest changed but far from

devastated.

Another change documented at the Agee fire involved deduction of the

fuel load. This is composed of dead and down sticks and logs, as well as

duff and needles. From a pre-burn level of 17.96 tons per acre, the fire

consumed 14.53 tons per acre of fuel. This 81 percent reduction

accomplished several things. Stored nutrients were released, making them

available for future plant growth. In addition, such reduction can

prevent the unnatural build up of fuels (which can lead to high

intensity fires) that results from overzealous suppression of all

fires.

Suppression of all fire at Crater Lake National Park was practiced

for roughly 75 years. During that time much natural change in the forest

has been stymied. When the snow began to fall in early November, there

was still heat in the Agee Fire. By this time the fire crews were long

gone and the fire cache was closed for the year. Snow fell gently and

the temperature hovered around 30 degrees. Standing in the midst of the

burn, I warmed my hands over embers in a slowly burning log. I thought

about the regrowth, elk, and more fires in the summer of 1995.

Further Information

James K. Agee, Fire Ecology of the Pacific Northwest Forests.

Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1993.

C.B. Chappell, Fire Ecology and Seedling Establishment in Shasta

Red Fir Forests of Crater Lake National Park. M.S. thesis,

University of Washington, Seattle, 1991.

Doug Lowthian is a seasonal firefighter at Crater Lake

National Park.

Phantom Ship from Kerr Notch in 1936. Homer Marion

photo, NPS files.

|