|

Volume XXVI - 1995

Ancient Remnants in Snow Crater

By Steve Mark and Ron Mastrogiuseppe

Craters are geological features usually associated with composite

volcanoes and the top of cinder cones. Found throughout the park, they

are generally less than a kilometer (5/8 mile) across and formed when

volcanic material is ejected through a vent of an active volcano.

Calderas, by contrast, represent volcanism far beyond the activity that

is typical of eruptions associated with craters. To put this in

perspective, the four to six mile-wide depression filled by Crater Lake

is a caldera while the crater on Wizard Island's summit is only a couple

of hundred yards across.

Wizard Island has a crater; Crater Lake is inside a

caldera.

|

That crater on Wizard Island formed after Mount Mazama's climactic

eruption, so it is clearly discernible. Cinder cones such as Crater

Peak, Maklaks Crater, Red Cone, and a number of unnamed points on the

park map have craters obscured by erosion, pumice and ash because they

appeared prior to the cataclysmic event of roughly 7,700 years ago.

Although not abundant, the park contains several post-Mazama craters

in addition to the one on top of Wizard Island. One easily reached by a

short walk from the west rim drive near Hillman Peak is Williams Crater,

sometimes called Forgotten Crater on older maps. Another one is located

some distance from any road, near the park's south boundary. Scoria Cone

is quite unlike the other two, in that it has an exposed crater-like

depression or what some geologists have described as a pit crater.

Most, if not all, of Scoria Cone resulted from a north-south fissure

through which lava extruded 25,000 to 45,000 years ago. It is one of

three prominent cinder cones built on well-rounded lava flows whose

appearance show evidence of glaciation, much like those in the vicinity

of nearby Union Peak. Like many other cinder cones, Scoria Cone has a

crater filled with pumice and ash. There is, however, a deep rectangular

depression or pit on the north end of the older crater floor. Measuring

roughly a hundred yards long and 50 yards across, the pit has

precipitous walls dropping away some 130 feet to the top of a snow and

ice plug.

In the 1940s one park naturalist noticed that snow in this plug is

permanent, even when summer melting in other parts of the park has long

dispatched any sign of winter. He named it Snow Crater, not knowing that

the snow and ice extended 150 feet down a chimney which once provided

the conduit for lava sometime in the past. He could not know because few

people are foolhardy enough to try a descent to the plug, let alone

attempting to go between the conduit's walls and the ice.

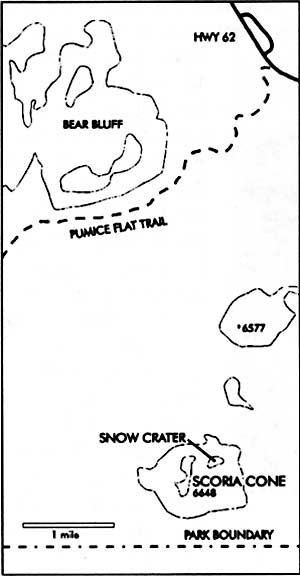

Map by Susan Marvin.

Even so, in 1977, after one of the driest years on record, a team of

park rangers explored where no one had ever been previously. They

reached the plug's bottom and found several rooms of various sizes. Two

of the rangers retrieved pieces of wood entombed in ice from near the

bottom of the plug. One of these specimens was subsequently identified

as Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii, by a wood technologist at

Washington State University. Its resting place piqued the curiosity of

researchers connected with the park, as no Douglas-fir are known to

occur presently at 6,300 feet anywhere near Crater Lake. Although badly

degraded, the wood showed breakdown in cellular structure that is caused

by hot water or steam. This led to speculation that the fragment might

have been in the pit crater while it was still active.

Although radiocarbon dating of this wood held the prospect of

providing additional insight to mysteries surrounding volcanic activity

at Scoria Cone and the vegetation history of this area, no one could

secure funding for necessary laboratory work for the next 17 years. Only

in 1994 did a sample specimen finally reach a radiocarbon dating lab for

an age determination. After calibration (since radiocarbon years may be

tree ring corrected to reflect calendar years) it was reckoned that this

piece of Douglas-fir is approximately 3,640 years old. The obvious

interpretation of this evidence is that a mixed conifer forest, as seen

today in the park's panhandle (the irregularly-shaped parcel of land

near the south entrance), flourished at Scoria Cone during a period of

warm-dry summer climate roughly 4,000 years before the present. Since

conifers such as Douglas-fir are long-lived, the wood sample may indeed

be one of the last of this species to grow near what became Snow Crater

at Scoria Cone. The nearest forest of similar composition 3,600 years

later is located a few miles downslope, but at 4,500 feet in elevation

near the park's south boundary.

Since three of us felt the need to locate any Douglas-fir presently

living close to Scoria Cone other than those previously mentioned, we

hiked there on August 25, 1994. After 30 minutes on the Pumice Flat

Trail, it took another hour or so by traversing cross country to reach

the top of a cone just north of our destination. We could find no

evidence of Douglas-fir along the way, nor did any appear on the short

jaunt to Scoria Cone. Instead we found a subalpine forest of lodgepole

pine, Pinus contorta v. murrayana, western white pine, Pinus

monticola, true fir (white fir, Abies concolor, and red or

noble fir, A. magnifica-procera), and mountain hemlock, Tsuga

mertensiana.

Once we reached Snow Crater, it did not take long to realize why the

rangers of 17 years earlier felt justified in closing this vent to any

future explorations. Remnants of wooden park signs to this effect could

still be seen as we walked around the pit's perimeter. It was then that

our attention became riveted to a curious three-needled pine clinging to

the precipitous north wall some 200 feet above the plug of snow and ice.

Just why it is there constitutes an interesting question. Surprisingly

enough, what has been called Ponderosa pine, Pinus ponderosa, in

lower elevation mixed conifer habitats can be found today in small

subalpine habitats near Crater Lake's caldera rim, and on warmer

southwest slopes of cinder cones within and near the park. In addition

to the possibility of this three-needled pine being ponderosa, there are

at least two others. These include Jeffrey pine, Pinus jeffreyi,

whose northern distribution is on serpentine substrates near the

Illinois Valley over 100 miles southwest of Crater Lake, and Washoe

Pine, Pinus washoensis, a rare and almost unknown species found

in the mountains bordering the Great Basin.

Trees can often serve as thermometers with sensitivity to

temperature changes induced by fluctuations in climate. Cold abbreviates

the length of growing seasons, thereby limiting critical processes such

as photosynthesis. The result is a narrow growth ring and long periods

without viable seed production. Even cold-hardy ponderosa pines would

find survival in the short growing seasons and frequent deep snowpacks

of subalpine habitats difficult.

The mixed conifer forest (with Douglas-fir as an associate) seen

today within the neighborhood of the park's panhandle has not always

been situated there. At the time of Mt. Mazama's great eruption, 7,700

years ago, a climatic interval known as the Altithermal or Hypsithermal

Period was underway. It began some 8,000 years ago and persisted for

approximately four millennia. Marked by significantly warmer and dryer

summers than at present, this time featured climatic changes which

altered growing conditions which favored the upslope migration of the

mixed conifer forest. Associated advances and retreats of forest

community borders along elevational gradients are well documented

throughout western North America.

Changes in vegetation zone elevations are affected by shifts in

critical growing season temperature and moisture regimes. A shift to

cooler, more moist conditions following the Altithermal Period spurred a

retreat of the mixed conifer forest to lower elevation habitats over the

past few thousand years. Isolated and disjunct stands of three-needled

pines within the subalpine zone today represent local pine variants. As

relicts of past environments, they may link prehistoric forest

assemblages to our time and place. The sentinel pine grasping the

volcanic rock for moisture and nutrients above Snow Crater may hold one

key for gaining a better understanding of the linkage between past and

present. Our visit to Scoria Cone provided an opportunity to interpret

the present scene and wonder about the relationships resulting from

those geologic, climatic, and biological forces present during the era

when a 12,000 foot Mount Mazama dominated the landscape.

Steve Mark is the park historian at Crater Lake. He has been

editor of Nature Notes since its revival in 1992.

Ron Mastrogiuseppe is a former seasonal employee at Crater Lake.

He is now based in Burns, Oregon, where he is an ecologist.

Panorama of Mt. Mazama from the southwest, sketched

by Howel Williams.

Howel Williams, The Geology of Crater Lake

National Park, Oregon, Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of

Washington, 1942, p. 66.

|