|

Volume XXVIII - 1997

Crater Lake in Indian Tradition: Sacred Landscapes and Cultural Survival

By Robert H. Winthrop

Introduction

Crater Lake and its environs served a range of uses for the Klamath,

Upper Umpqua, and other Indian peoples of the region. The area of what

is now Crater Lake National Park was used for both hunting and

gathering. Huckleberry Mountain, an important gathering site for the

Klamath, lies about ten miles southwest of the lake. Nonetheless, the

primary significance of Crater Lake appears to have been as a place of

power and peril, renowned as a spirit quest site, yet also feared for

the dangerous beings residing in the lake. In short, Crater Lake

constituted a sacred landscape, that is, a region distinguished in the

traditions of a people by its special spiritual qualities or

powers.1

The aim of this paper is to make such an alien reality somewhat more

intelligible, both as a matter of cultural interest, and for its

relevance to the sensitive management of this remarkable national park.

I argue that there are, in fact, significant parallels as well as

dramatic differences in Anglo-American and Indian perceptions of such

sacred landscapes. Such a comparison can suggest both the degree of

common concern for such geographies of refuge and transcendence, and

what we as Anglo-Americans could usefully learn from the far more

nuanced and complex appreciation of such landscapes inherent in Indian

traditions.

Nature as sublime experience

Given the numerous controversies which have arisen since the 1970s

over proposed development of lands viewed by Indian peoples as sacred or

culturally sensitive, it is worth emphasizing that Anglo-American

culture has also seen in nature an avenue for spiritual

experience.2 The romantic movement, in particular, strongly

influenced the perception of wilderness in nineteenth century America.

Denis Cosgrove, in his interesting study of society and symbolic

landscapes, noted that in America,

...by the 1820s and 1830s the idea of romantic landscape had invested

scenes of wild grandeur with a special significance. They were held by

many to be places which declared the great forces of nature, the hand of

the creator.... In the context of a religious tradition which stressed

individual salvation, the idea of sublime wilderness offered a powerful

opportunity for transcendence, a way of appropriating America as a

distinctive experience unavailable in Europe.3

Crater Lake, first encountered by Anglo-American travelers in the

1850s, admirably fulfilled the desire for a sublime and inspiring

experience of nature. Captain Franklin Sprague, describing his visit in

1865, spoke of the lake's "majestic beauties" and "awful

grandeur."4 Clarence Dutton remarked in 1886 on the emotional

reaction which the lake aroused in its visitors:

It was touching to see the worthy but untutored people, who had

ridden a hundred miles in freight-wagons to behold it, vainly striving

to keep back tears as they poured forth their exclamations of wonder and

joy akin to pain.5

John Wesley Powell, writing in 1888 in support of a bill to create a

national park to protect Crater Lake, argued,

The lake itself is a unique object, as much so as Niagara, and the

effect which it produces upon the mind of the beholder is at once

powerful and enduring. There are probably not many natural objects in

the world which impress the average spectator with so deep a sense of

the beauty and majesty of nature.6

Similarly, Mark Daniels, former General Superintendent of the

National Parks, said of Crater Lake:

The sight of it fills one with more conflicting emotions than any

other scene with which I am familiar. It is at once weird, fascinating,

enchanting, repellent, of exquisite beauty and at times terrifying in

its austere-dignity [sic] and oppressing stillness.7

Enraptured by the sublime: a 19th century visitor at

the rim.

Peter Britt photo, 1874. Southern Oregon Historical

Society #704, Medford.

What is particularly intriguing about these expressions of

geopiety to borrow a term from the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan -- is

the way in which they manifest both strong similarities and differences

with the Indian experience of the Crater Lake region. The similarities

lie in the common recognition of an encounter with the alien, the weird,

and the numinous in this ancient caldera. Yet the differences are also

telling. For the American explorers and settlers, the encounter with

Crater Lake appears to have yielded a deep emotional response, but not a

deeper knowledge or transformation of self. Such testimonies as these

suggest an awareness of the sacred, but it is a mute awareness, a matter

of mood. Unlike the Indian visitors to Crater Lake, the Anglo-American

travelers lacked the cultural models -- the cognitive templates

encompassing mythology, ritual practices, and knowledge of localized

spirit beings -- which allow such encounters to yield a message, to

produce lasting understanding and personal change.

This bafflement in the face of mute nature is captured well in a

passage from the modern nature writer Edward Abbey. Of his travels in

the American Southwest, he says,

I consider the tree, the lonely cloud, the sandstone bedrock on this

part of the world and pray -- in my fashion -- for a vision of truth. I

listen for signals from the sun, but that distant music is too high and

pure for the human ear.8

Nature as sacred landscape

The Indian conception of Crater Lake was a matter of much comment by

travelers and settlers of the region. The Portland Oregonian

reported in 1886 that,

There is probably no point of interest in America that so completely

overcomes the ordinary Indian with fear as Crater lake. From time

immemorial no power has been strong enough to induce them to approach

within sight of it. For a paltry sum they will engage to guide you

thither, but before reaching the mountain top will leave you to proceed

alone. To the savage mind it is clothed with a deep veil of mystery and

is the abode of all manner of demons and unshapely

monsters.9

Similarly, George Kirkman, writing in Harper's Weekly in

1896, described the small island in the lake known as the Phantom Ship

as "a fantastic object of unspeakable dread to the Klamath

Indians."10 These accounts, however exaggerated and in part

factually incorrect, do convey a sense of Crater Lake and its environs

as an area set apart, in some fashion fundamentally different in quality

from the wider region, the southern Oregon Cascades.

For the Klamath, spirit power could be found in many

sources.11 The spiritual significance of gi-was, or

Crater Lake, reflected a more general Klamath understanding of the

natural world, involving not only reverence but the possibility of

significant interaction with particular mountains, lakes, and streams,

as an individual sought comfort, assistance, or power.12 As

one Klamath woman commented in the late 1940s:

...those old Indians had a lot of sense. They kind of felt at home

around here and they would get a lift from just talking to the mountains

and lakes. It was like praying and it made them feel at

peace.13

In a sense features in a sacred landscape are persons: one can enter

into relationships with them. A Klamath woman about 80 years old,

paralyzed and bedridden, said:

Every day I pray to the mountain. I lie here in my bed and I am sick

and old and every morning I say to those mountains, I say, "Bless me,

help me." I pray just like my mother taught me to do.... My mother

taught me to pray to rocks and mountains and to give some food to them

before we eat. It's just like in the Bible. I dream of those mountains

at night. They kind of help you when you ask it.14

The elements of a sacred landscape derive their power in part from a

net of symbolic associations accruing from myth. Crater Lake figures

prominently in the myth of Le*w and Sqel. Le*w is "the monster who

dwells in Crater Lake .... rather octopoidal and of a dirty white

color."15 The myth relates his battle with Sqel (who also

appears as Old Marten or Old Mink), a culture transformer in Klamath

tradition, "teaching subsistence techniques, and generally preparing the

world for the myth age humans."16

The myth opens with Sqel/Mink/Old Marten and his friend Weasel. They

are tricked by the beautiful but wicked daughter of Le*w, who

ingratiates herself with Mink (or in an alternate version, Weasel), and

tears out his heart. She then takes the heart to Le*w's people at Crater

Lake, who play ball with it. Weasel runs for help to Gmokamc, the

Klamath creator figure, who advises Weasel, and then proceeds with the

help of various allies to recover Mink's heart. Mink revives, but Le*w

now carries him off to Crater Lake, and is about to cut him to pieces

and feed him to his children, the crawfish. However, Mink outwits Le*w

and slays him, cutting up his body and (pretending the pieces belong to

Mink's own corpse) feeding them to the crawfish. Finally Mink throws

Le*w's head into Crater Lake, naming it correctly. In Theodore Stern's

translation of a version narrated by Herbert Nelson:

Then he [Mink] threw into the water all this, heart,

windpipe-and-lungs, and liver. "Here's Mink's heart, windpipe-and-lungs,

and liver!" Now the Crawfish came and ate all that. "Then here's

Lao's [Le*w's] head!" Bawak! sound of head splashing into

the water. The Crawfish recognizing their father scattered in all

directions. Then that head of Lao's lodged there. This is Wizard

Island.17

While Anglo-American travelers' claims that Indians did not visit

Crater Lake are false, the area was certainly regarded as the abode of

powerful spirits. Traditionally, gaining a vision of such beings was a

major goal of the spirit quest.18 The seeker would often swim

at night, underwater, to encounter the spirits lurking in the depths of

the lake.19 Leslie Spier commented regarding the father of

one of his informants, "having lost a child, he went swimming in Crater

lake; before evening he had become a shaman."20 The quest for

such spirits required courage and resolution:

He must not be frightened even if he sees something moving under the

water. He prays before diving, 'I want to be a shaman. Give me power.

Catch me. I need the power.'21

One Klamath woman recounted seeing a spirit being on the lake:

When I was young, I went up to Crater Lake with a woman I knew. She

tied my eyes and led my horse.... Then she said, "Untie your eyes," and

I nearly fell off the horse. I saw a man standing on the water far away,

just like in the Bible. He scared me so, I don't know who that was, but

I like to think of that man now.22

Individuals undertook strenuous and dangerous climbs along the

caldera wall. Some would run, starting at the western rim and running

down the wall of the crater to the lake. One who could reach the lake

without falling was thought to have superior spirit powers. Sometimes

such quests were undertaken by groups. Rocks were often piled as feats

of endurance and evidence of spiritual effort. Four of the five

prehistoric sites thus far identified at the park are in fact piled rock

sites. Here as elsewhere, such sites are usually built on peaks or

ridges, with fine views. Leslie Spier reported one such named site built

on a point of rock projecting from the western wall of the lake. Today

Crater Lake remains important as a site for power quests and other

spiritual pursuits, particularly for members of the Klamath Tribe.

Conclusions

To recapitulate: what has been termed here a sacred landscape

entails a correlation of physical place and cultural meaning, existing

within a larger body of tradition. Its physical elements (a piled rock

site, Wizard Island, the lake bottom) have associations with various

culturally postulated events, some in a mythic time, others occurring

still today. Those who share traditional knowledge of a landscape such

as Crater Lake bring to the encounter culturally patterned expectations

which shape experience, form symbolic associations, and allow lasting

experiential value to be gained.

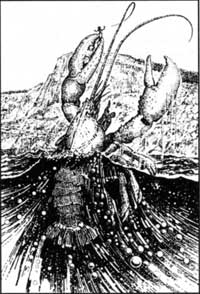

Llao, chief spirit of Crater Lake, controlled many

lesser spirits who appeared in the shape of animals. One such monster

was a giant crayfish who could pluck unwary visitors from the crater rim

and drag them down to the dark, chilling depths.

NPS drawing, Harpers

Ferry Center.

|

Under such circumstances the tenacity with which many Indian tribes

struggle to preserve their sacred landscapes is understandable, for such

areas offer the possibility of sustaining tradition and identity, thus

linking the future with the past. The attempt by Karok, Yurok, and other

Northwest California peoples to preserve the "High Country" of Del Norte

County from logging -- the so-called G-O Road case, fought all the way

to the U.S. Supreme Court -- offers a recent example (see Lyng v.

Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, 485 U.S. 439

[1988]).

Within contemporary Anglo-American culture, there is evidence of a

collective effort to discover or create such sacred landscapes. The

ethos of sublime nature -- which a century ago moved the "worthy but

untutored" visitors to Crater Lake to tears -- is apparently no longer

sufficient. Today Anglo-Americans are rather ingenuously urged to seek

out "sacred places" culled from the most diverse

traditions.23 The acts of the more radical environmental

movements (for example, those defending old growth forest); and the

vague nature mysticism, coupled with imitation of things Indian, which

suffuses many popular therapies -- men's groups taking to the woods to

sharpen spears and chant -- likewise seem directed toward fashioning

sacred places within an increasingly disenchanted world. Whether it is

culturally feasible deliberately to create ritual, myth, and sacred

landscapes remains to be seen.

This paper has benefited significantly from the assistance of

Gordon Bettles, Director of the Cultural Heritage Program, Klamath Tribe

(Chiloquin, Oregon); and from Sue Shaffer, Chair of the Cow Creek Band

of Umpqua Tribe of Indians (Canyonville, Oregon). Part of the material

presented here is taken from a cultural resource overview of Crater Lake

National Park, prepared for the National Park Service (Contract

CX-9000-9-P013). Support by the NPS, and in particular James Thomson and

Fred York of the Seattle Office, is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

1 Regarding sacred space or sacred landscape, see chapter

one in Mircea Eliade (Willard R. Trask, trans.), The Sacred and the

Profane: the Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt, Brace &

World, 1959); Linda Grabner, Wilderness as Sacred Space

(Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers, 1976); Yi-Fu Tuan,

Geopiety: A Theme in Man's Attachment to Nature and to Place, in

David Lowenthal and Martyn J. Bowden (eds.), Geographies of the

Mind (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976); and Deward E.

Walker, Jr., Protecting American Indian Sacred Geography, Northwest

Anthropological Research Notes22 (1988), pp. 253-66.

2 Diane Brazen Gould, The First Amendment and the

American Indian Religious Freedom Act: An Approach to Protecting Native

American Religion, Iowa Law Review 11 (1986), pp. 869-91; Richard W.

Stoffle and Michael J. Evans, Holistic Conservation and Cultural

Triage: American Indian Perspectives on Cultural Resources, Human

Organization 49 (1990), pp. 91-99.

3 Cosgrove, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape

(Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble, 1984), p. 185.

4 Linda W. Greene, Historic Resource Study: Crater Lake

National Park, Oregon (Denver: USDI-NPS, 1984), p. 271.

5 Harlan D. Unrau, Administrative History, Crater Lake

National Park, Oregon (Denver: USDI-NPS, 1988), p. 32.

6 Ibid., p. 33.

7 Ibid., p. 233

8 Grabner, p. 44.

9 Green, p. 28.

10 Ibid., p. 29

11 Robert F. Spencer, Native Myth and Modern Religion

among the Klamath Indians, Journal of American Folklore 65

(1952), pp. 217-26.

12 M.A.R. Barker, Klamath Directory, University of

California Publications in Linguistics 31 (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1963), p. 145.

13 Spencer, p. 223.

14 Ibid., p. 222.

15 Barker, p. 215.

16 Ibid., p. 389.

17 Theodore Stem, trans., [Myth of] Crater Lake (Lao's

Daughter), narrated in Klamath by Herbert Nelson, 1951. MS on file at

Crater Lake National Park.

18 Spencer, p. 222.

19 Leslie Spier, Klamath Ethnography, University of

California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 30

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1930), p. 98.

20 Ibid., p. 96.

21 Ibid.

22 Spencer, p. 222.

23 James A. Swan, Sacred Places: How the Living Earth

Seeks Our Friendship (Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Co., 1990).

|