|

GRAND TETON NATURE NOTES

|

| Vol. II |

Autumn, 1936 |

No. 4. |

|

ACTIVITY AT THE LIMESTONE WALL

by Howard R. Stagner

During the past summer and fall a great column of rock became

detached from the Limestone Wall, and in settling, resulted in the

destruction of a portion of the Skyline Trail which passes in front of

it. It is not unusual for large masses of rock to become dislodged from

cliffs and steep canon walls and to fall to the depths below. In this

particular case, however, the movement and the resulting destruction of

the trail were accomplished in a more indirect manner, and the event is

considered worthy of recording in Nature Notes.

The Limestone Wall encircles the broad head of Avalanche Canon, and

forms the west boundary of Grand Teton National Park. It lies above

timberline at an elevation of about 10,500 feet above sea level. A

narrow ledge about half way up the eastern exposed face of the wall was

followed in locating the Skyline Trail where it crosses Avalanche Canon.

Below this shelf steep talus slopes form a continuous grade downward to

the canon floor, interrupted here and there by exposed ledges of

limestone. Above the trail massive beds of limestone rise in vertical

columns and walls to a height of several hundred feet.

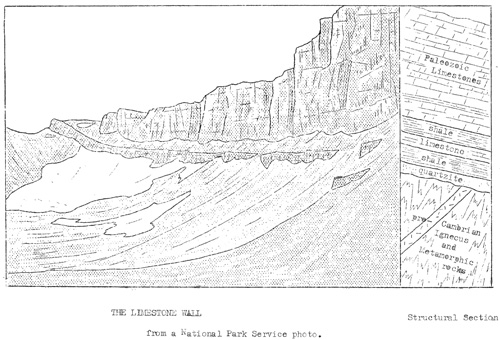

The wall itself is formed of the exposed edges of several Paleozoic

limestone formations. These dip toward the west at an angle of about 10

degrees, and rest on a series of Cambrian formations consisting, from

the base upward, of a quartzite, a shale, a limestone and a second shale

bed.

The limestone formations of the wall are massively bedded, but as a

structural feature the stratification is much less prominent on the face

of the wall than are vertical cracks opened by weathering along two sets

of joints. The joints run through the limestone formations in two

directions at right angles to each other and to the stratification.

It is the normal thing for huge blocks of rock formed into

parallelograms along the joints and bedding planes, or for great columns

of rock bounded by vertical joints to become separated slowly from the

wall and to plunge into the bottom of the canon. Eight such columns are

now in the process of formation. One of those columns, some 150 feet

high, 100 feet wide at the base, and 30-40 feet thick, provided an

interesting variation to the normal process.

The first indication that something was happening along the wall came

when a part of the Skyline Trail caved away and large cracks developed

between the trail and the loosened cloumn. The cracks were at least ten

feet deep, and much loose rock and soil disappeared into them without

accomplishing any apparent filling.

At first it was believed that the base of the column was slowly

swinging outward from the trail and was thus pushing directly against

the trail and in this manner destroying it. That the column was actually

pushing outward was apparent from observations and measurements made

along its base, but that this was not the entire explanation was

suggested by the large cracks between the moving column and the trail

itself. How could the column be pushing the trail away when not only was

the column not in contact with the trail, but in fact was separated from

it by a ten inch crack?

THE LIMESTONE WALL

(click on image for a PDF version)

Considerable speculation by Engineer McLellan of the National Park

Service and the writer resulted in the development of two possible

explanations. The first required that a considerable portion of the base

of the column be buried by talus. In this case, with the top of the

column resting against the wall with no outward movement taking place,

then the pivotal outward swing of the base would push most against the

deeper portion of the talus. The overlying talus would, of course, be

carried outward an equal distance as it rode upon the deeper talus, but

the higher part of the column, being closer to the pivotal point, would

move outward through a shorter distance to leave the observed cracks

between it and the surface of the talus.

The second explanation also involved a carrying of the trail

outward by the deeper moving material rather than a direct

pushing action of the column on the trail. In this explanation it

is believed that as the heavy column settled into the underlying shale,

this soft material moved out from beneath the column in the only

unconfined direction- outward away from the wall and away from the

moving column, and as it "flowed" outward carried with it the talus on

which the trail was located. The cracks developed as the the talus was

carried outward away from the column by the deeper shale. In both cases

the outward movement was sufficient to to dislodge the outer part of the

trail which fell to the lower talus slopes.

The fact that a large snowfield remained on this portion of the trail

and along the base of the wall throughout most of the summer, providing,

as it melted, a constant supply of water to saturate and lubricate the

shale, is probably of some significance. Although shale is known to flow

under great earth pressure- geologists frequently encounter examples of

such flowage in the limbs of folds- probably such a movement would not

be possible at the surface of the earth and under such moderate

pressures unless the shale were so saturated and lubricated.

There is evidence to support each of these two theories. An

examination of the relative positions of the limestone, shale and talus

along other parts of the wall indicated that not a large portion of the

base of the column is buried by talus- not enough to alone account for

the cracks as the first explanation requires. In support of this

explanation, however, the outward movement of the column was several

inches in excess of the downward settling. It is probable that both

these processes acting together produced the effects described.

At the time of the last visit to the wall, October 17, the column had

settled from 4 to 10 inches, had moved outward about 14 inches at the

base, and had pivoted to the south from 4 to 6 inches. It was believed

at that time that the column could not long stand, but on November 1,the

wall was viewed through binoculars from a vantage point on the east side

of the Snake river in Jackson's Hole, and the column was still standing.

Immediately below the column, however, fresh snow that had fallen a few

days earlier, was covered with rock debris apparently loosened by new

movements of the column. Future developments will be followed with

considerable interest.

|