|

GRAND TETON NATURE NOTES

|

| Vol. III |

Winter 1937 |

No. 1. |

|

TETON GEOLOGICAL NOTES - No. 1

THE GLACIATION OF JACKSON HOLE

by Dr. F. M. Fryxell

The geological record from which one may decipher the glacial history

of the Teton Range is found in part within the mountains themselves, in

part outside them, especially in adjacent Jackson Hole.

To many visitors, speeding up the state highway, the flats of Jackson

Hole may seem to offer little that is worth a second glance. But the

geologist will recognize on the valley floor a great diversity of

ridges, terraces, channels, and depressions, features that furnish the

key to the glacial events which have occurred both in the valley and in

the great range to the west.

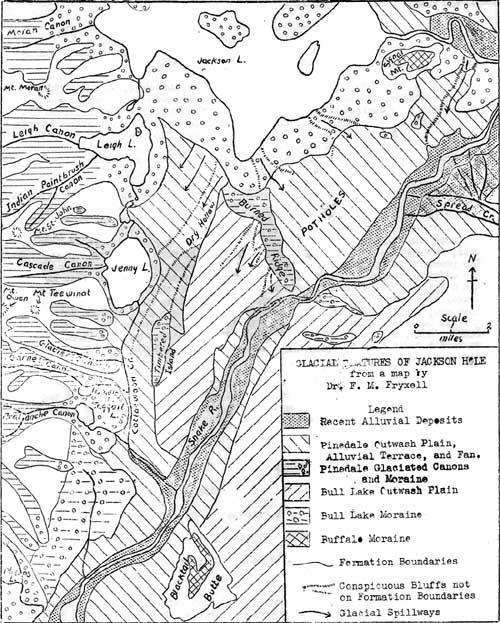

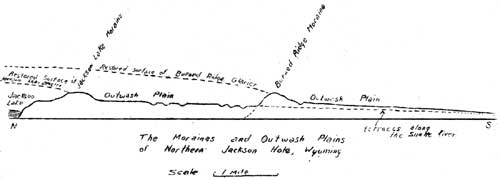

To grasp the significance of these features one can do no better than

visit the east tip of the main section of Burned Ridge (see map, page

3), and from this point, with the Narrows of the Snake River directly

below, survey the country to the north and south.

(click on image for a PDF version)

Here one sees that Jackson Hole is diagonally crossed by two low,

wooded ridges: Burned Ridge on which we stand, and another ridge several

miles to the north, that follows the south border of Jackson Lake.

Around this northerly ridge the Snake River makes a circuitous eastward

journey whence it turns southwestward and directly through Burned Ridge

to form the Narrows at our feet. Were we to examine more closely, we

would discover that both of these ridges are irregular and hummocky of

surface, and composed of cobbles and boulders many of which are striated

— proof that they were transported by glaciers, and that therefore

the ridges themselves are typical glacial moraines.

Equally distinct from our viewpoint are two broad plains which extend

outward from these ridges and slope evenly southward. Unlike the ridges

from which they emerge, these plains are overgrown with sagebrush; hence

the moraines and the glacial outwash plains — for such they are

— are strikingly distinct. Composed of porous quartzite gravel with

little or no soil they constitute barren ground indeed for anything but

sage. Both of the outwash plains are deeply trenched by the Snake River,

and the northerly plain is continued south of the Narrows by terraces

that border the Snake River well beyond Blacktail Butte, where they

widen into the swampy flats of the southern part of Jackson Hole.

The meaning of these features now becomes evident, for they can mean

only this: that northern Jackson Hole was at two distinct times

invaded by a glacier. These two times of glaciation must correspond to

those which geologists have reported from the Wind River Mountains and

elsewhere, on the basis of similar records there found. For the earlier

of these times the term "Bull Lake Stage" is generally used; for the

latter, "Pinedale Stage". In terms of these stages then, one may briefly

review the glacial events of this region:

In the Bull Lake Stage a glacier (The Burned Ridge Glacier) entered

the valley from the north and northwest, and advanced as far as Burned

Ridge. At this position it must have stood for a time long enough to

permit the ice to heap up the Burned Ridge moraine, and the glacial

streams to deposit the outwash plain extending southward from it. The

plain must have reached unbrokenly around and beyond Blacktail Butte,

into the most southerly reaches of Jackson Hole.

In time the Burned Ridge Glacier melted back from its moraine, and

eventually disappeared altogether. Did a large lake come into existence

in the basin behind Burned Ridge? If so (as seems probable) it must have

been drained during the interglacial stage which followed — an

interval of long duration in the course of which streams greatly reduced

the extent of Burned Ridge, trenched the outwash plain between the

Narrows and Blacktail Butte, and in southern Jackson Hole largely eroded

away similar Bull Lake deposits.

The task of the streams was arrested unfinished, when in Pinedale

time glacial conditions returned. Again a glacier (the "Jackson Lake

Glacier") pushed into the north end of the valley, fed chiefly by

smaller glaciers which occupied the Teton canons. In its southward

growth it advanced over the same path as its predecessor of the Bull

Lake Stage. The moraine of this glacier indicates that its front must

have shifted back and forth. The large size of the Jackson Lake moraine

is evidence of a prolonged stand in this position, but there are

"islands" of moraine farther south, protruding from the outwash plain.

That the ice front got farther south than even these "islands" is

indicated by the pitted areas (locally called "the potholes") which lie

between them and Burned Ridge. Presumably these pits mark situations

where the glacier, in retreating, left behind it masses of stagnant ice

which had separated from its main body. These ice masses became

surrounded or buried by outwash gravels, which, when the ice later

melted out, slumped in to produce depressions in the otherwise even

outwash plain. Since pits of this sort extend all the way to Burned

Ridge, one is led to conclude that the Jackson Lake Glacier for at least

a brief time reached as far south as this ridge, that is, it practically

attained the same limits as did the Burned Ridge Glacier long

before.

From this shifting ice front vast quantities of outwash gravel were

carried out by short-lived glacial streams. These were deposited not

only on the main outwash plain but within the river trench south of the

Narrows and on the valley floor in southern Jackson Hole.

Jackson Lake came into existence as the glacier retreated from the

Jackson Lake Moraine, and the water was dammed between the moraine and

the ice front. With the complete disappearance of the ice the lake

assumed essentially its present size and shape.

What of the Tetons during the two glacial stages? Here, as one might

expect occurred similar events. Valley glaciers descended the canons and

pushed out into Jackson Hole. The moraines left by the Bull Lake

glaciers are now in most places eroded away, but Timbered Island and the

high bench extending along the mountain front southward from Taggart

Lake appear to be extensive remnants of Bull Lake moraine. The Pinedale

moraines, in marked contrast, are beautifully preserved, and form the

basins which are responsible for the existence of Phelps, Taggart,

Bradley, Jenny and Leigh Lakes.

But the glacial story can be pushed back yet another chapter. For

evidence of this one must climb to the summits of Signal Mountain,

Blacktail Butte, or one of the Gros Ventre Buttes. In these surprising

situations one again discovers striated boulders and cobbles — mere

patches of ancient moraine, like tattered manuscripts. Similar deposits

occur on the highlands east of Jackson Hole, capping the intercanyon

divides 1000 feet or more above the valley floor. The presence of

morainal remnants in such situations, and their absence in the adjacent

canyons, can be accounted for only by the assumption that there was a

third glaciation which occurred much earlier than even the Bull Lake

Stage, at a remote time when the floor of Jackson Hole was 1000 feet

higher than now, and the present system of canyons which open into

Jackson Hole had not yet been cut. This stage, which likewise has been

recognized far outside Jackson Hole, has been named the "Buffalo Stage".

Scanty as its record is we cannot doubt that this, the earliest of the

three glaciations, was much the most widespread.

Thus, what we commonly call the "Ice Age" or "Glacial Period" (the

"Pleistocene Period" in geological terminology), which lasted perhaps

two million years, really involved no less than three distinct times of

glaciation, and two of deglaciation. These may be tabularly represented

as follows:

Postglacial time

Subdivisions

of the

Pleistocene

Period |

|

( Pinedale Glacial Stage (3rd glaciation) |

| ( |

| ( Later Interglacial Stage |

| ( |

| ( Bull Lake Glacial Stage (2nd glaciation) |

| ( |

| ( Earlier Interglacial Stage |

| ( |

| ( Buffalo Glacial Stage (1st glaciation) |

Preglacial time

The three glaciations were successively less extensive, and the later

of the two interglacial stages was of briefer duration than the earlier.

What of postglacial time, which represents the briefest interval of all?

Is it truly postglacial, or are we now living in a third interglacial

stage? To this question geology has as yet no positive answer, though

investigation now in progress leads one to hope that a future solution

is not improbable.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|