|

GRAND TETON NATURE NOTES

|

| Vol. V |

Spring 1939 |

No. 1. |

|

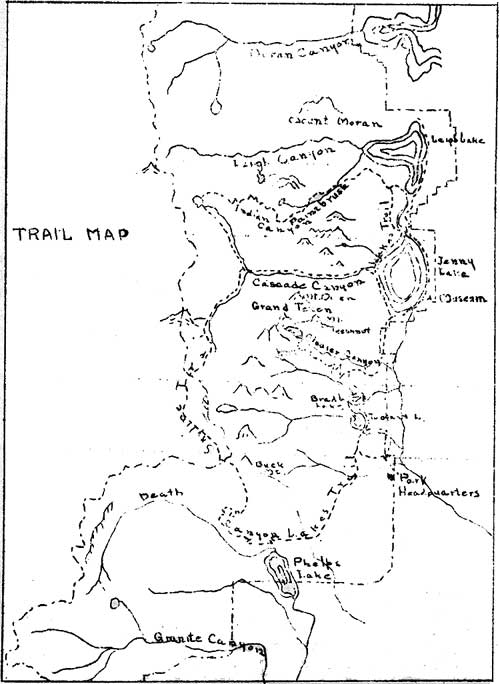

TRAILS IN GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK

by

Bennett T. Gale

It is felt appropriate at this time to devote a portion of the

current issue of Nature Notes to a brief discussion of the hiking and

saddle horse trails in Grand Teton National Park. The construction of

the Alaska Basin trail last year has brought about completion of the

major part of our trail building program. It is by the use of these

trails that access is made into the more remote areas of the park. The

trail system makes available all characteristic sections of the park and

at the same time leaves large areas of untouched wilderness.

We can divide our trail system into four groups: The Lakes Trail, the

Canyon Trails, the Skyline Trail and the Glacier Trail. We will discuss

each group in order.

(click on image for a PDF version)

The Lakes Trail

The Lakes Trail runs parallel to the Teton Range closely following

the base of the mountains and skirts the shore of each large lake from

Leigh Lake on the north to Phelps Lake on the south. It is the trail by

which all the other trails are reached and is the one from which all

expeditions into the mountains or canyons begin.

No other trail within the park offers so many opportunities for

wildlife study as does the Lakes Trail. The larger animals frequent the

terrain which this trail makes available. The outlet of Leigh Lake, the

marshy ground at the foot of Mt. Teewinot, the Grand Teton and Nez Perce

Peak, the country near the Whitegrass Ranch and the Phelps Lake area are

all fine feeding grounds for Shiras moose (Alces americana shirasi).

Travelers along the trail, particularly in the early morning and

evening, are seldom disappointed in obtaining glimpses of this large

ungainly creature. The graceful blacktailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus

macrotis) inhabits the forests and grassy meadows along the trail.

Occasionally the American wapiti or elk (Cervus canadensis) can be seen

at the mouth of the canyons but this animal is not often found in the

park during the summer. Early and late in the season the black bear

(Euarctos americanus cinomomum) may be observed from this trail. The

only remaining antelope (Antilocapra americana americana americana) in

Jackson Hole may be seen at the Whitegrass Ranch on a short detour from

the trail.

A good representative cross section of the smaller animals can also

be seen from the Lakes Trail. Perhaps the most interesting being the

beaver (Castor canadensis). There are numerous localities along the

trail where the beavers are active, notably just west of park

headquarters, Leigh Lake and Bear Paw Lake to the north of Leigh Lake.

The marmot or rockchuck (Marmota flaviventris nosophora) is common along

this trail. Occasionally the rare black variety is seen, although this

unique Teton melanistic specimen is more often encountered at higher

elevations. Both the golden-mantled ground squirrel (Callospermophilus

lateralis cinerascens) and the Uinta ground squirrel (Citellus armatus)

are met. The pine squirrel (Sciurus hudsonicus ventorum) and the

chipmunk (Eutamias) are frequently seen. More rarely observed in rock

slides along the trail is the curious little cony or pika (Ochotona

princeps ventorum). The yellow-haired porcupine (Erethizon epaxanthum

epaxanthum) is fairly common. The snow shoe rabbit (Lopus bairdii

bairdii) is also frequently soon.

More of the park's hundred species of birds can be seen in the area

traversed by this trail than in any other section of the park. Space

does not permit enumeration of the species that may be seen.

The flora along the Lakes Trail is that characteristic of the

piedmont area of the park. The forests are predominately lodgepole pine

(Pinus contorta) and alpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa). Along the streams

and lakes the Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmanni) is found. The stately

Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga taxifolia) is occasionally seen. A varying

wildflower exhibit is seen along the trail. The forested zones, the

grassy meadows and the open flats each have their characteristic

brilliantly hued display changing with the season but always bright and

appealing.

The traveler along this trail has ample opportunity to observe the

geology of the mountain slopes and adjacent areas. He can study the

pre-Cambrian crystalline rocks that make up the eastern mass of the

Tetons. The trail crosses the glacial moraines in front of all the

canyons from Indian Paintbrush on the north to Death Canyon on the

south. In several localities the trail drops to the sagebrush covered

outwash plains of Jackson Hole. At the southern end of the trail one

notices the sedimentary rocks that begin to overlap the crystalline

rocks of the mountains in this area.

The Canyon Trails

Only three of the intermountain canyons of Grand Teton National Park

have been penetrated by trails. The remaining canyons have been left as

truly wilderness areas and help preserve this park as a primitive one.

The three canyons in which trail construction has been carried on are

all quite distinctive and give the visitor an outline of the entire park

area. The canyons reached by trail are Indian Paintbrush Canyon, Cascade

Canyon and Death Canyon.

Indian Paintbrush Canyon - The trail up this canyon leaves the

Lakes Trail in the moraine built up by the glacier that once flowed down

Indian Paintbrush Canyon. As the morainic material is left behind and

the hiker or rider reaches the canyon proper, he passes through a

beautiful stand of Engelmann spruce and then enters more open country

filled with wildlife and a profusion of wildflowers among them the

colorful paintbrush (Castilleja) for which the canyon is named. The trip

up the canyon is one filled with evidences of past glaciation. Smoothed

and polished rock is noted, glacial "benched" are seen, high on the

canyon walls are hanging valleys, small ridges of morainic material

appear and several abandoned cirques such as Holly Lake can be made out,

until finally the summit plateau is reached.

The summit plateau lying between Paintbrush and Cascade Canyons is of

particular interest as it is in such contract to the glacially

sculptured jagged peaks and ridges of the Tetons. Is this the

re-exposure of the ancient pre-Cambrian land surface or the remnants of

a later peneplaination? The trail crosses this intriguing plateau and

crosses the divide between Cascade and Leigh Canyons and thence down a

long slope into North Cascade Canyon, Lake Solitude and the Skyline

Trail.

Cascade Canyon - By far the most popular trail in the park is

the lower portion of the Cascade Canyon Trail which leaves Jenny Lake

and climbs above Hidden Falls. Throughout this area there is a fine

stand of Engelmann spruce. The erosive action of moving ice can be

observed in the polished and pitted surface of the canyon floor.

Visitors are sometimes fortunate enough to see the water ousel (Cinclus

mexicanus unicolor) sporting in the foam and spray of Hidden Falls.

Above the falls, there is a fine view east across Jenny Lake and its

encircling moraine, the floor of Jackson Hole and to the Gros Ventre

Mountains east of the main valley.

The trail above Hidden Falls to the forks of Cascade Creek and the

Skyline Trail passes through a glaciated chasm whose walls rise above

the canyon floor for thousands of feet. The agents of weathering are

active in this area and there are many rock slides and talus slopes of

very recent origins

Death Canyon - The trail up Death Canyon strikingly

illustrates the differing topographic forms that develop in the two rock

types of the park. In the lower eastern portion of the canyon are found

the jagged peaks, spires and pinnacles that erosion has carved in the

crystalline gneisses and granites of this part of the range. In the

upper reaches of the canyon are the more rounded, subdued and gabled

forms of the slightly inclined sedimentary beds of the western part of

the area. The sunny meadows in the upper canyon are gardens of

wildflowers, a startling contrast to the awesome depths of the lower

canyon.

The Skyline Trail

The Skyline Trail connects the Indian Paintbrush, Cascade and Death

Canyon trails. On this trail the visitor travels to the west of the

major peaks of the range and obtains new and impressive views of the

Tetons.

The trail from beautiful Lake Solitude lies in North Cascade Canyon,

a remarkably glacially smoothed canyon with an abundance of wildflowers

and many of the smaller animals of the park in evidence. The trail joins

the Cascade Canyon trail and proceeds up the South Fork of Cascade

Canyon. As the higher elevations are reached the whitebark pine (Pinus

albicauli) becomes the predominant tree and this in turn gradually

becomes dwarfed as the traveler approaches timberline. The upper portion

of South Cascade Canyon resembles the summit plateau between Indian

Paintbrush and Cascade Canyons, a more or less level exposure of the

pre-Cambrian gneisses and granites. Table Mountain to the west shows

many beds of sedimentary rock and the existence of an east-west fault is

at once evident.

The hiker or rider now climbs the ridge marking the watershed west of

the Tetons passing a small glacier enclosed by its moraine. As the slope

is climbed one can see the earlier sediments overlying the pre-Cambrian

complex. The lowest formation is the Flathead quartzite with its basal

conglomerate. Above this lies the Gros Ventre formation of shales

interspaced with a bluish gray limestone, and above the Gros Ventre is

the massive gray limestone of the Gallatin. Descending into Alaska Basin

it is possible to recognize other later sediments including the Bighorn

dolomite and the Madison-Brazer limestone.

The trail out of Alaska Basin passes near two old prospector's holes

in which a little copper "color" can be seen. As Buck Mountain is

reached the beds of Flathead quartzite are more and more inclined and

finally are seen in an almost perpendicular attitude. This evidence of

faulting suggests the reason for the older pre-Cambrian rocks of the

mountain mass lying at higher elevations than the younger sedimentary

beds just to the west.

The Skyline Trail crosses the watershed once again and climbs high on

a shoulder of Buck Mountain. From the top a fine view is obtained to the

east and Jackson Hole, and to the west toward Idaho. The trail drops

rapidly through forests of whitebark pine and finally joins the Death

Canyon Trail.

The Glacier Trail

The Glacier Trail is that section of the trail system which climbs

the east slope of the Grand Teton to Surprise and Amphitheater Lakes at

elevations of nearly 10,000 feet. From Amphitheater Lake it is possible

to scramble over loose morainic rock and reach Teton Glacier the most

accessible of the ice fields in Grand Teton National Park.

All along this trail the hiker or rider has opportunity to observe

the effect of glaciation in the mountains and in the valley below. As

one leaves the Lakes Trail he has just crossed a morainic ridge piled up

between glaciers that once were active in the gullys to each side. As he

climbs up the switchbacks on the east slope of the Grand Teton he is

able to see how the glaciers scoured out the canyons and then deposited

their load in the valley below. The piedmont lakes below are all

enclosed in their wooded, horseshoe-shaped moraines. The outwash plains

of Jackson Hole can be seen and the evidences of previous glaciation may

be noted in the wooded areas of Timbered Island and Burned Ridge. At the

end of the trail the two alpine lakes lie in their glacially scoured

cirques. When the traveler has climbed the ridge above Amphitheater Lake

he obtains a most startling view of the force and power of moving ice.

Glacier Canyon lies below him scoured by the glacier whose remnant now

is confined to the cirque at the head of the canyon. Far below can be

seen little Delta Lake excavated by the plucking action of the ice as it

rode over the rock floor of its valley. The turquoise of this tarn

testifies to the grinding action of the present glacier breaking up its

burden of rock into finely powdered "flour". With considerable effort

the climber crosses boulder fields and climbs up the loose slopes of the

moraine enclosing Teton Glacier. From the top he can cross debris laden

terrain and reach the ice itself. Here it is possible to gain first hand

knowledge of the work of glaciers. The surface of the ice is littered

with rock debris. The undermining of the rock walls of the cirque

results in the falling of rock from high in the walls. Some of the rock

material is left standing on pillars of ice above the general level due

to differential melting. If fortunate, the visitor can see one of these

perched boulders slide from its table and travel down the slope of the

ice. Cracks or crevasses open up on the ice due to stresses developed by

an uneven floor below the glacier. Into these cracks rock material falls

and helps the glacier in its rasping action. With these features in mind

the visitor has a much more real understanding of the results he sees

below and better realizes the extent of the work of glaciers long since

inactive.

The glacial story is not all that interests the traveler along the

Glacier Trail. As one leaves the Lakes Trail he is in lodgepole forests.

As he goes up the slope he comes into timber of the alpine fir and the

large Douglas fir. Then, higher up, he enters the whitebark pine zone

which extends to timberline. All along the way is a profusion of

wildflowers which become alpine in form as Surprise and Amphitheater

Lakes are reached.

A few animals and birds may be seen along this trail. The larger

animals are fairly well confined to the lower elevations but several of

the smaller species may be seen. The pika, squirrels and chipmunk are

common. The marmot is frequently seen and the black variety is sometimes

encountered at the two alpine lakes. The most common bird is the Clark's

crow or nutcracker (Nutcifraga columbiana) seen breaking open the cones

of the whitebark pine.

|