|

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace

Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter Three:

THE DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION OF THE LINCOLN BIRTHPLACE MEMORIAL, 1906-1911

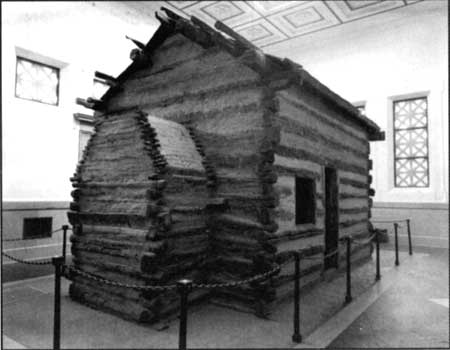

In the months following February 1908, less than a year before the centennial of Lincoln's birth, the directors of the Lincoln Farm Association realized that their limited funds would not provide for the construction of a memorial museum dedicated to Abraham Lincoln. The revised and simplified building program required only that the Memorial Building, as it came to be called, properly honor the memory of Lincoln and that it enshrine the Lincoln birth cabin. The architect, John Russell Pope, already having developed an initial scheme for a large museum building and formal landscape at the site, incorporated much of his original design into the scaled down plan. However, because the Lincoln Memorial Building had to enclose and protect another structure and allow for a constant flow of visitors, Pope created a building without an equal among American museums and memorial buildings. The building can be seen as both a memorial to the birthplace of Lincoln and as a museum displaying one, very significant, artifact. No precedent existed for such a memorial to a cabin, but Pope successfully integrated symbolic and functional architecture to create a very powerful, commemorative experience for the visitor.

Despite Pope's unique architectural vision for the Lincoln Memorial Building, all memorial architecture in America up to that time was part of a long legacy of memorialization using symbolic and architectural forms passed down through the ages. This chapter briefly traces that legacy, and then focuses on the particular events leading up to and through the construction of the Lincoln Memorial Building.

ANCIENT AND CLASSICAL ROOTS OF AMERICAN MEMORIAL

ARCHITECTURE

|

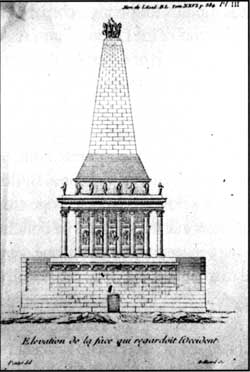

| Figure 27: Artist's conception of the Tomb of Mausolus (c. 1700s) |

American memorial architecture, especially the design of large memorial buildings, has long been rooted in the architectural forms of ancient Greece, Rome, and later European architecture. Importantly, the concept of memorialization the honoring of the memory, deeds, and life of an important person or persons—grew out of universal concepts relating to honoring the dead, worshipping deities, and maintaining the immortal spirit of the deceased. In both Europe and America, ancient architectural forms such as pyramids, tombs, temples, and mausolea, along with smaller sculptural objects such as obelisks and columns, were adapted over time to serve particular memorial purposes.

Funerary architecture is intrinsically related to the concept of the memorial, and by its very nature serves a similar purpose. However, while all funerary monuments are memorials, not all memorials are funerary. As the word implies, memorials often honor only the memory of people or events, and they are not contingent upon the presence of the body or bodies of the deceased. Yet because much of the same emotion and symbolism is intrinsic to both funerary and non-funerary memorials, many of the same architectural and symbolic forms are used. In both ancient and modern times, all memorials used freestanding, sculptural objects such as the obelisk, column, and statue, and enclosing structures such as the tomb, sarcophagus, and mausoleum. Very often, a combination of one or more of these forms would be used in conjunction with a larger building.

One form of ancient funerary architecture, the mausoleum, became a form commonly used in later European memorials. The term mausoleum is derived from the burial tomb of the ancient Carian king Mausolus (c. 377-353 B.C.). The tomb of Mausolus, one of the "Seven Ancient Wonders of the World," was one example of a type of above-ground, circular funerary building that became popular in Greece during the Hellenistic period. Similar circular tombs were built at Delphi and Epidaurus, and all had antecedents in the domed, subterranean Tholoi of ancient Mycenae. Importantly, however these new mausolea were intended to be highly visible structures, serving to bring the burial place of notable individuals out of the earth for all to see and honor. Although mausolea were common in Hellenistic Greece, it was in Rome that the mausoleum as a building type flourished. Cylindrical tombs, developed from the Etruscan tumulus, and rectangular tombs, in the form of temples, were typical. Square, octagonal, and tower forms were also common.

During the Ages, the use of the mausoleum declined as burials were incorporated into churches or replaced by sculptural monuments. [1] A revival of the mausoleum occurred in England in the early eighteenth century with the development of the informal garden. By the end of that century, tombs and mausolea were common features of European estates. The mausoleum inspired related building types during this period. Cenotaphs, usually of imposing scale, honor the memory of persons buried elsewhere. Temple forms and architectural follies were built with no purpose other than the addition of an architectural element to the garden to evoke images of ancient idyllic landscapes. [2]

The mausolea constructed throughout the eighteenth century in England, and later in France, were mostly based on forms found in antiquity: the pyramid, square, circle, octagon, and obelisk. These were built with great variation and some forms, such as the pyramid and obelisk, were more common than others. Permanence, monumentality, and immortality were associated with the pyramid, contributing to its popularity in funerary architecture. [3] The mausoleum at Blickling, Norfolk, designed by Joseph Bonomi in 1794, is the first mausoleum of pyramidal form erected in England. [4] Measuring forty-five feet on each side and forty feet tall, the simple form and smooth ashlar walls are interrupted only by the square windows and entrance. The interior is domed and contains arcaded niches.

|

|

The obelisk, also derived from ancient Egypt, was commonly incorporated into mausoleum designs. Obelisks brought from Egypt were erected throughout ancient Rome and later reerected by Pope Sixtus Vat the close of the sixteenth century. In antiquity, however obelisks symbolized the sun-god and were rarely used as funerary symbols. [5] John Carr's design for Rockingham Mausoleum at Wentworth Woodhouse, Yorkshire, of 1783-88, is among the first mausolea in England to include an obelisk. As planned, the tomb featured a vaulted burial chamber surmounted by a seventy-five-foot obelisk.

Ancient victory columns, similar to the obelisk form, inspired the introduction of new architectural forms in neo-classical Europe. Trajan's Column, erected in Rome in 107-113, is the quintessential model. It is a 125-foot marble column set on a high podium and topped with a statue of the emperor. The actual shaft is adorned with low relief sculptures in a 600-foot continuous spiral that present a visual narrative of Trajan's triumph over the Dacians. The podium, or base, contained a burial chamber for the emperor's ashes. The Colonne Vendome in Paris, built 1806-10, and the Nelson Column in Dublin of 1808, for ex ample, were influenced by Trajan's Column, although they never served a funerary function. The popularity of the obelisk and column can, in part, be attributed to revivalism, exoticism, Romantic Classicism, and the influence of the French Academy and its educational arm, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. [6]

Circular and square temple forms with a rotunda blended with the landscape gardens of neo-classical England and were commonly scaled down and reconfigured to function as funerary monuments. Robert Adam's mausoleum for the Johnson family at Dumfriesshire, Scotland (1790), incorporates an applied tetrastyle temple-front on a square plan temple with a saucer dome. Chambers's more elaborate but unrealized designs for the mausoleum of Frederick, Prince of Wales (1751-52), feature a domed, circular-planned tomb with obelisks at the four corners of the podium. [7]

THE PUBLIC MEMORIAL IN EUROPE

|

| Figure 30: Pantheon in Paris, France |

The distinction as to whether a memorial was public or private has always been ambiguous. While the ancient mausolea of Greece and Rome were public in the sense that they could be viewed, the circulation of the public through their interior spaces was limited. They stood as symbols of family prestige and power. During the nineteenth century in Europe, this ambiguity was accentuated, because the same architectural forms served as both public and private memorials. Usually, the expense and location of a memorial suggested its place in the public or private domain. [8] Complicating the matter further the interiors of mausolea often featured private commemorations exclusive of their public exteriors. Public mausolea, of primary concern to this context, will be defined as buildings, usually monumental in scale, that can be entered by the public, with the principal commemoration focused inside the building at the place of burial.

The ancient forms that inspired the designs of small neo-classical tombs in Europe also provided design sources for the public mausoleum. Designs for the monumental tombs, like the smaller, private mausolea, combined Greek and Roman temple forms with the needs of a burial site. Among the most significant public mausolea of the period is the Pantheon in Paris, designed by Jacques-Germain Soufflot, and erected from 1764 to 1790. Originally designed as a church, the Pantheon was rededicated in 1791 as a secular national memorial temple, and contains the remains of Mirabeau, Voltaire, Rousseau, and Victor Hugo among others. Its plan is a Greek cross with a dome and peristyle drum over the crossing. The large entrance portico is based on that of the Pantheon in Rome.

|

| Figure 31: Walhalla |

Buildings were also constructed at this time to honor national heroes without containing their remains, closer to the tradition of the ancients. In the early nineteenth century, Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria began collecting busts and statues to include in a temple honoring Germany's heroes. Walhalla, located near Regensburg, was de signed by Leo von Klenze between 1821 and 1827 and was completed in 1842. The marble temple, set on a hill above the Danube River was modeled on the Parthenon. German historical and allegorical scenes replaced images of Greek gods, and a seated statue of Ludwig I dominates the hall in a manner similar to the colossal cult statue of Athena once contained in the main body (cella) of the Parthenon.

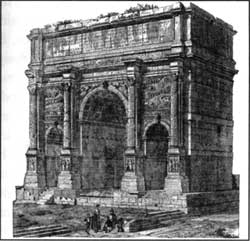

Numerous architectural forms derived from antiquity remained largely free of funerary associations and were purposefully erected in the public sphere. In ancient Rome, memorial arches, or triumphal arches, were erected by persons, often the emperor honoring themselves or with the purpose of commemorating an event, notably a military victory. The most common types featured a single arch, such as the Arch of Trajan, built in 117, or a large, center arch flanked by two smaller arches, exemplified by the Arch of Septimus Severus, erected in the Forum Romanun in 203. These monumental stone arches functioned as large city gates or entrances to fora. Rich ornamentation included architectural elements, such as columns and entablature; sculptural elements, both relief and in the round; and incised text, usually in the attic level, explaining the dedication of the monument. Although the finest examples survive in Rome, nearly 150 triumphal arches can be found throughout the Roman Empire.

|

| Figure 32: Arch of Septimus Severus |

The triumphal arch was usually limited to commemorating martial events and individuals, but this did not diminish its popularity in neo-classical Europe. The Arc du Carrousel in Paris, designed by Percier and Fontaine in 1806-07, is modeled after the Arch of Septimus Severus. Erected by Napoleon I at the site of the Tuileries, the three-arched monument celebrates Napoleon's military achievements through relief sculpture, life-size figures, and a quadriga that surmounts the center arch. Napoleon began construction of a second monumental arch, far exceeding the scale achieved by the ancient Romans. The Arc de Triomphe, designed by Chalgrin in 1806 and completed in 1835, commemorates Napoleon's military victories, although Napoleon actually dedicated the monument to his soldiers and sailors. The single-arched monument measures 160 feet tall, 150 feet wide, with a depth of 72 feet. Similar arches, although constructed on a smaller scale, were built in England at this time and include John Nash's Marble Arch in London of 1828.

Events in Revolutionary France precipitated a change in memorial architecture, as memorials to events and ideals replaced monuments to individuals. Portrait busts and equestrian monuments dedicated to dynastic rulers gave way to monuments commemorating themes such as liberty and democracy. Although glorification of the individual returned with Napoleon, architecture, much of it derived from funerary forms, re placed sculpture as the primary means of commemorating the achievements of individuals as well as more abstract concepts. [9] Although other ancient forms of architecture, such as the triumphal arch and temple, contributed to the development of the public memorial, the column, and more significantly the obelisk, were most often chosen to honor important events and individuals in the United States. [10]

THE PUBLIC MEMORIAL IN THE UNITED STATES

|

| Figure 33: Baltimore Washington Monument |

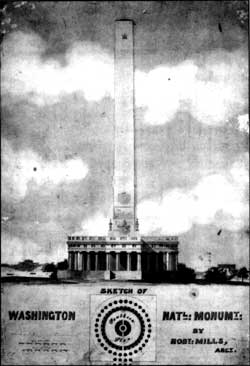

The first large-scale public memorials erected in the United States followed the War of 1812. In the twenty-five years following the Revolution and the establishment of the American government, the public's desire for large-scale commemorative monuments intensified. Based on European models, early American monuments featured simple iconographic programs, free of the complex allegories that characterized English and French neo-classical monuments. Al though the relative merits of the obelisk and column were debated, both were viewed as the most effective architectural forms for symbolizing a single idea or gesture. [11] Robert Mills, considered the first American-born professional architect, designed many early monuments, including two of the nation's most significant memorials: the Baltimore Washington Monument and the Washington National Monument. The deification of Washington began long before his death in December 1799, and the dedication of a memorial in his honor seemed certain. In 1811, the first of six lotteries, authorized by the Maryland General Assembly, was held, eventually raising enough funds to construct a Washington monument in Baltimore. Mills's design was chosen in an architectural competition in 1813. The white marble monument rises 175 feet and consists of three main elements: a low, rectangular base containing a museum; a plain, unfluted column; and, atop the column, a standing figure of Washington. By the time of the monument's completion in 1829, financial constraints had forced a series of design compromises. Early designs included rich ornamentation, six iron galleries dividing the hollow shaft into seven sections, and a quadriga surmounting the column. The design of the completed column is very similar to the Colonne Vendome, which ultimately derived from Trajan's Column.

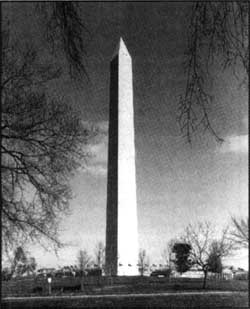

Columns utilized in a memorial context, however, never achieved the popularity or the widespread use of the obelisk. The Bunker Hill Monument, designed by Solomon Willard in 1825, commemorates the Revolutionary War battle fought there June 17, 1775, and is the first monumental obelisk built in the United States. In choosing an obelisk over a column for the Bunker Hill Monument, Horatio Greenough reasoned that the obelisk was "complete in itself; the column normally stood beneath the weight of a pediment and supported an entablature. It was taken out of a created unity to become a new and inappropriate whole when utilized as a monument." [12] As a practical matter, the column is simply a pedestal to support a sculpture while the "complete" obelisk offers four flat sides for virtually unlimited inscriptions. Mills also recommended constructing an obelisk at Bunker Hill, noting "its lofty character, great strength, and furnishing a fine surface for inscriptions," and because it "combined simplicity and economy with grandeur." [13] Some later analyses have suggested phallic associations with memorial columns and obelisks, pointing to the almost universal fact that they were made by, and honored, men. Whatever the motivation, it was the obelisk that captured the fancy of most memorial designers during the nineteenth century.

| ||

|

The Washington National Monument was designed by Robert Mills from 1845 to 1852 and is among the seminal public memorials erected in nineteenth-century America. Efforts to raise the one million dollars needed to complete a monument concentrated on donations from patriotic Americans which would not exceed one dollar. []14 After five years, only $31,000 had been collected, and in 1845, the monument committee accepted a proposal by Mills estimated to cost $200,000. Mills's de sign consisted of a 600-foot obelisk rising from a colonnaded pantheon 100 feet tall and 250 feet in diameter. The interior was to contain statues of the signers of the Declaration of In dependence and paintings depicting events in American history. The decorated obelisk emphasized Washington's military career. Design sources for this form can be traced to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century interpretations of the appearance of ancient mausolea, including the aforementioned tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassos and Hadrian's Tomb. [15]

Completed by Thomas L. Casey in 1884, the obelisk was reduced in height to 555 feet, and much of the decoration was eliminated. The pantheon surrounding the base was also eliminated, thus creating a monument dedicated solely to Washington. It was constructed of smooth white granite with a plain finish and exceeded the height of all previously erected monuments. The grand scale of the Washington Monument served to validate an already popular architectural form. Nine of the first sixteen Presidents are commemorated with obelisks at their places of birth and/or burial sites: Washing ton, Jefferson, Madison, Jackson, Van Buren, Tyler Fillmore, Pierce, and Lincoln.

During the nineteenth century, American public memorials, especially memorials with patriotic themes, were thought to improve "national morality" and the "national principles" themselves. [16] Petitions appealing for a Washington monument warned that "inattention to the fame, and insensibility to the merits of those who magnanimously protected and laboriously achieved our liberties, may be justly viewed as the decay of that public virtue which is the only solid and natural foundation for a free government." [17] Monuments served to "resharpen distinctions which have grown ambiguous and symbolized creeds and principles in danger of being forgotten." [18] Without a king and imposing ceremony, the United States had few obvious external forms of government. Monuments made the abstract tangible, evoking feelings of patriotism and pride and connected people with the "idea of country." [19]

The majority of post-Civil War memorials erected in the United States were either statues or what were commonly referred to as shafts. This category included obelisks, columns, and other tower-like forms. Beginning in the mid-1860s, large numbers of shafts were built to honor the war dead. These shafts, also called soldier's monuments, were frequently topped with an allegorical figure or soldier and included highly decorated bases with inscriptions. [20] Historian David M. Kahn asserts that the popular use of shafts and their close relationship to funerary architecture resulted from the sudden demand for monuments at the end of the war and the lack of an American memorial architecture other than funerary monuments. [21]

Memorial architecture forms derived from antiquity and revived in neo-classical Europe remained popular in the United States through the nineteenth century. In 1800, Benjamin West, President of the British Royal Academy, asked English architect George Dance to produce de signs for a monument to George Washington. Dance sketched three proposals based on a pyramid form, similar to European monuments such as the mausoleum at Blickling. Ornamental pyramids constructed of uncoursed rubble mark the birthplaces of Presidents Polk, erected in 1904, and Buchanan, built after 1868. The pyramid form was also deemed appropriate to commemorate Civil War dead; a rusticated granite pyramid erected in 1869 in Richmond, Virginia, honors 18,000 Confederate soldiers killed during the war. [22]

In a design competition for the Baltimore Washington Monument, French architects Maximilian Godefroy and Joseph Ramee each submitted designs for triumphal arches based on neo-classical models. Triumphal arches gained currency at the end of the nineteenth century with the ebb of picturesque eclecticism and the rise of Beaux-Arts classicism. George B. Keller's Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial Arch in Hartford, Connecticut, built 1884-1886, illustrates the former with its rusticated Gothic arch and conical towers. [23] Contemporaneously, McKim, Mead and White designed two monumental arches in New York, the arch in Prospect Park of 1888-89 and the Washington Memorial Arch in Washington Square of 1889-92. Both single arches incorporate elaborate sculptural programs reminiscent of classical and Napoleonic arches. [24]

|

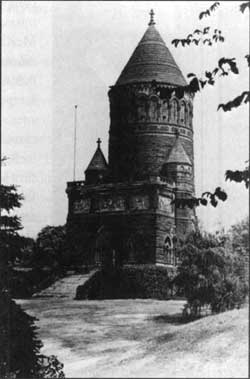

| Figure 36: Tomb of James A. Garfield, Cleveland, Ohio |

Public mausolea, also derived from ancient and neo-classical sources, were first con structed in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century. Private, small-scale mausolea were erected throughout the century but remained largely in cemeteries. These were designed in the popular styles of their day, including Egyptian revival, Romanesque revival, and High Victorian Gothic. The tomb of James Monroe, built in 1858 when the president was reinterred in Richmond, Virginia's Hollywood Cemetery, is a typical example. Resembling a large reliquary, it is constructed of iron in the Gothic Revival style and includes lancet and trefoil windows, colonettes, and finials. [25]

The Lincoln Mausoleum in Springfield, Illinois (see Fig. 9), established an early American prototype for the monumental public tomb. The tomb was designed by sculptor Larkin G. Mead in 1869 and completed under the supervision of Russell Sturgis in 1874. As rebuilt in 1900-01, the 117-foot tall granite monument is composed of an obelisk set on a base that contains the Lincoln family burials. A statue of Lincoln at the base of the obelisk is surrounded by four bronze military groups. The mausoleum contained Lincoln artifacts, statues of Lincoln, and relief scenes of the President's life. The tomb is closer to sculpture than architecture, and represents only a partial realization of the public mausolea. The interior memorial spaces were secondary to the exterior sculptural expression, and the rotunda and burial chamber were sealed in 1930-31. [26]

The tomb of James A. Garfield, located in Cleveland, Ohio, represents the first American mausoleum to serve as a public memorial, focusing memorial efforts inside the building. Designed by George B. Keller in 1885 and completed in 1889, the tomb expresses both the Romanesque and Gothic idioms in an original composition. The building is comprised of a circular tower which encloses the memorial chapel and Garfield's crypt, two engaged stair towers, and a three-portal, rectangular entrance block. [27] Funds for the memorial were raised by a popular subscription, with its sponsors referring to it as "the first real Mausoleum ever to be erected to the honor of an American statesman." [28]

The Garfield tomb is among the first complete expressions of the public mausoleum, with interior spaces provided for the contemplation of the late president. Although Keller gave much thought to the exterior appearance of the tomb, its mission remained unfulfilled until the visitor entered the chapel and burial chamber. Constructed shortly after Garfield's tomb, the mausolea of Presidents Grant and McKinley were designed in this new form of American funerary architecture and are discussed below.

JOHN RUSSELL POPE AND THE LINCOLN BIRTHPLACE MEMORIAL,

1906-1911

In late 1906, the Lincoln Farm Association (LFA) commissioned landscape architects Jules Guérin and Guy Lowell to develop a plan for a memorial building and landscape treatment. [29] The preliminary plan, published in a series of views in Collier's Weekly, included a historical museum, a statue of Lincoln. and a formal landscape. [30] A tree-lined avenue linked the Lincoln farm with the town of Hodgenville, three miles to the north. A copy of Augustus Saint-Gaudens's Standing Lincoln was to be placed at the intersection of this avenue and a short allee that terminated at the historical museum. A bird's-eye view of the museum depicts a three-part composition with two colossal columns flanking the main entrance. A detail of the proposed museum, however resembles the south facade of the White House. The surrounding cultivated fields and the proposed meandering paths contrast sharply with the formal landscape.

|

| Figure 37: John Russell Pope |

In April 1907, the Board of Directors of the LFA asked board member Thomas Hastings, of the architectural firm Carrere and Hastings, to "select a group of architects to compete for the design of the Memorial Building." [31] The architect Charles F. McKim was invited to participate in the selection process. Rather than establishing an architectural competition, McKim and Hastings simply awarded the commission to the promising young architect John Russell Pope. McKim and Hastings devoted much of their careers to late-nineteenth-century classicism and their selection of Pope further reveals their views on classicism as the appropriate style for memorial architecture.

Pope was exposed to classicism at the outset of his career. During the 1880s, before reaching the age of seven teen, Pope entered the office of the New York architectural firm McKim, Mead and White, working closely with McKim for several years. [32] In 1891, Pope began his formal study of architecture under William R. Ware at Columbia University. He graduated in 1894, winning McKim's scholarship to the American Academy in Rome and a second award for travel. Pope spent two years in Greece and Italy, producing sketches and measured drawings of such monuments as the Acropolis and the Baths of Caracalla. In 1896, Pope traveled to Paris where he studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts from 1897 to 1899. Pope's "grand tour" of Europe and his education at the Ecole contributed to his eventual mastery of, and inclination towards, classical architecture.

The system of architectural education at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts was based on lectures and practical experience gained in ateliers, or studios, of established architects. Students advanced in the program through a series of design competitions; Pope won the Jean Le Claire Prize for architectural design in 1898. Central to the Ecole's system was the primacy of the parti, or central idea of a design as seen in its logical development. The classical orders and the decorative vocabulary of classical and Renaissance architecture were also emphasized. [33] The clarity of plan and circulation Pope learned at the Ecole can be seen in his early monumental work such as the Temple of the Scottish Rite in Washington, D.C., of 1910.

Building on his formal training at the Ecole, Pope developed his own classical manner in the United States, and continually refined his own architectural style until his death in 1937. All of his buildings are, arguably, in the classical style, but it became too easy for many critics to dismiss Pope's work as formulaic. According to Richard Chaffee, "Pope was the foremost inheritor of McKim's severe classicism," and Joseph Hudnut labeled him "The Last of the Romans." [34] Al though McKim undoubtedly influenced his designs, Pope's own particular interpretation of classical architecture resulted in distinctive compositions. Pope was adept at using building materials to accentuate the mass and volume of his works. Large blank walls devoid of ornamentation or fenestration gave a modernistic quality to many of Pope's buildings, even though they incorporated the reassuring vocabulary of the classical orders. The National Gallery is a prime example of this more restrained Beaux Arts classicism. Along with architects such as Bertram Goodhue and Paul Phillippe Cret, Pope sought to reinterpret the Beaux Arts style to create a distinctively American architectural idiom. [35] Importantly, Pope also understood the modern purposes that his buildings had to serve, and he saw in the logical plans and forms of classical architecture solutions to the practical problems of creating functional public buildings for a modern society. It would not be inaccurate to consider Pope a progressive classicist, one who used classical architecture as a foundation for contemporary architectural expressions. [36] As one more recent critic has argued of Pope's classicizing buildings, they are "neither copies nor revivals." [37]

|

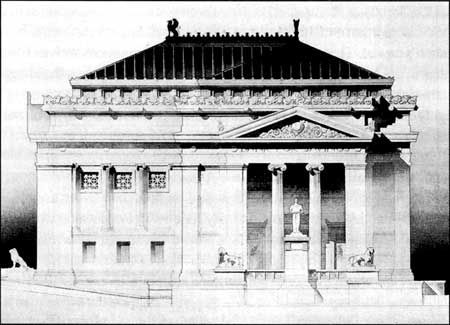

| Figure 38: This design for a savings bank won Pope the McKim Travelling Fellowship and the Rome Prize in 1895. |

As Chicago's Prairie School architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and European modernists such as Le Corbusier abandoned Beaux Arts classicism, Pope continued to design buildings in the classical tradition until his death in 1937. His buildings are known to anyone who has visited our nation's capital. These include the large, public commissions such as Constitution Hall of the Daughters of the American Revolution, 1929; the National Archives Building, 1933-35; the Jefferson Memorial, 1937; and the National Gallery of Art, 1937-41. Because of these highly public and highly cherished works, Pope's classical architecture remains symbolic of the ideals of American democracy.

POPE AND HIS DESIGNS FOR THE LINCOLN FARM ASSOCIATION

In 1900, Pope returned to New York from Paris, and worked for various architects, including Bruce Price, before establishing his own office. By June 1907, Pope was at work on plans for the LFA Memorial Building, and in February 1908, Collier's Weekly published two renderings of the Lincoln farm design. [38] The plan represents an elaboration of Guérin and Lowell's concept of a formal, linear landscape with a memorial building and sculptural element at each terminus and set within the picturesque landscape of the farm. The progression from the earlier plan is obvious: the museum has become the multi-purpose memorial hall; the Saint-Gaudens statue has been replaced by a memorial column marking Lincoln's birthplace; and the tree-lined allee has been expanded to a memorial plaza.

|

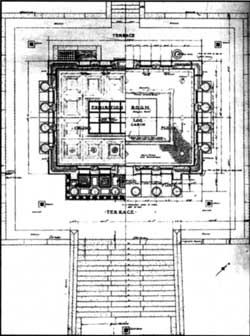

| Figure 39: Pope's first plan for a "Lincoln Birthplace Museum," 1907. This initial concept for a large museum was beyond the financial reach of the Lincoln Farm Association. |

The Memorial Building, estimated to cost $250,000, was the principal element of the commemorative landscape. It was a one-story, three-part Beaux-Arts classical building organized around an arcaded central court. As designed, the court had a removable roof that sheltered the birth cabin. The surrounding halls featured museum exhibits, and an auditorium was located in the main room. The main entrance was recessed and set within a triumphal arch that included four colossal columns in antis. [39]

The unornamented, planar wall surfaces of the proposed memorial building are characteristic of Pope's monumental designs and cam be seem in the tomb for William Batemam Leeds, a project Pope was completing while preparing designs for the LFA. The Leeds tomb, constructed in Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx, New York, built from 1907 to 1909, features smooth ashlar walls and a bold cornice with much of the ornamentation concentrated around the maim entrance, similar to the proposed memorial building. Architectural historian Stephen Bedford believes the main facade in Pope's preliminary memorial building design is based on McKim's 1907 Morgan Library in New York, which has a similar three-part organization and entry articulated as a "wafer thin triumphal arch." [40] Clearly pleased with this architectural vision for the LFA, Pope resurrected the design in 1928 when he was hired by the American Pharmaceutical Association to design their headquarters in Washington, D.C. The building is today considered one of Pope's best works. [41]

On the knoll where it was believed Lincoln's birth cabin originally stood, opposite the Memorial Building, Pope called for a monumental column. This "simple shaft" maybe a reworking of a lost drawing entitled "Design for a Commemorative Monument on the Great Lakes." [42]

|

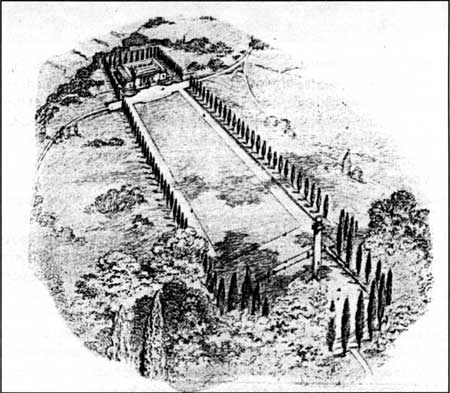

| Figure 40: A Bird's-Eye View of Pope's First Plan For a Lincoln Birthplace Memorial as Illustrated in a 1908 Issue of Collier's Weekly |

Pope may have been influenced by a series of monumental columns designed by Stanford White beginning with the unrealized 220-foot Detroit Bicentennial Column of 1899. White adapted this design for the 143-foot Prison Ship Martyr's Monument in Greene Park, Brooklyn, New York, of 1904-1909. In 1904, White designed the setting for Saint-Gaudens Seated Lincoln, located in Chicago's Grant Park. The design, which included two Doric columns, was not completed until the 1920's. [43]

Pope placed the Memorial Building and column at opposite ends of a long, rectangular grass plaza. The entire arrangement was surrounded by closely spaced Lombardy poplars, interrupted only by two meandering pathways. The trees focus attention on the Memorial Building and the column at opposite ends of the plaza, screening out the surrounding landscape. Con versely, views of the plaza and memorial structures could only be afforded from within the plaza. As compared to the Guérin and Lowell plan, Pope's design depicts a memorial that is somewhat isolated from the Lincoln farm and surrounding area.

The axial placement of horizontal and vertical elements and open space in Pope's first design for the Lincoln farm may have been inspired by the 1902 McMillan Commission Plan to re-establish Pierre Charles L'Enfant's original plan of then nation's capital, specifically, the portion of the Mall that included the Washington Monument, the reflecting pool, and the Lincoln Memorial. [44] Tellingly, the gentle grades depicted in Pope's renderings bear little resemblance to the hilly topography of the Lincoln farm and suggest that the drawings were produced before the architect visited the site. Regardless of the effect of the influential McMillan Commission Plan upon Pope's design for the Lincoln farm, a barrier other than topography would eventually confront the architect.

As Pope's plan was introduced in February 1908, the LFA had collected only $100,000 of the estimated $250,000 needed to complete the Memorial Building. [45] Funds were sought through Congressional appropriation, but none were forthcoming. [46] Between February and October 1908, less than one year before the centennial of Lincoln's birth and the projected dedication of the memorial, the LFA decided to modify the design in view of its limited financial resources.

In October 1908, Pope produced a set of eleven drawings — elevations, plans, and sections — that depict the Memorial Building largely as it was completed. [47] As suggested by the drawings, the memorial efforts shifted from a memorial museum and landscape to a more modest memorial building to enshrine the birth cabin with a landscaped approach. The Beaux-Arts classical building was constructed by Norcross Brothers Construction Company of Worcester Massachusetts, the nation's first general contractor and one of the most important construction companies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

As built, the Memorial Building is situated on the knoll where some believed the Lincoln birth cabin originally stood. The difference between Pope's original and revised plans reflects a fundamental change in the way Pope integrated the natural topography of the site with his architecture. No doubt recognizing the dramatic perspective afforded by the knoll, Pope placed the Memorial Building on this natural pedestal and used its incline for a dramatic stairway approach. Four sets of granite stairs ascend the terraced hill. Nearly thirty-seven feet wide at the base, the stairs narrow to thirty feet at the summit. [48]

|

| Figure 41: Assembled crowd at the 1911 dedication of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial |

Pope's rising, processional approach to the Memorial Building was enhanced by his landscaping plan, an arrangement of ornamental hedges, trees, and open space evocative of his original plaza plan of 1908, albeit placed on an inclined plane. At the 1911 dedication, the landscape consisted of terraced grass panels outlined by low hedges with an additional parallel line of hedges that flanked the stairs. A row of Lombardy poplars was planted just outside and parallel to each of the the two outside hedgelines. The October drawings do not include this landscape, but photographs from the 1911 dedication ceremony indicate that these plantings were in place, including the Lombardy poplars. [49] The stairway included pea gravel landings at the top of each set of stairs. Pope also included a large gravel entry plaza with a central flagpole at the foot of the stairway. The court was bordered by low hedges, effectively defining the entire memorial site as separate from the rest of the farm property. This open area at the foot of the stairs provided the visitor a dramatic perspective of the Memorial Building high in the distance, a goal to be reached by gradual accent. Just as it did in his original plan, Pope's use of Lombardy poplars created a simple but powerful framework for the entire setting.

The Sinking Spring, located just west of the stairs, remained in its natural state and the remaining grounds were grassed, wooded, or under cultivation. Visitors entered the court from the south and the east. Four pink granite markers, two incised with "Lincoln Birthplace Memorial," marked the unpaved entrance road.

The formal landscape Pope conceived for the Memorial Building was very similar to the McKinley National Memorial. Designed by New York architect Harold Van Buren Magonigle, the McKinley Memorial was dedicated in September 1907, four months after Pope began work on plans for the Lincoln farm. The pink granite mausoleum is circular in plan with a diameter of seventy-five feet and features a dome and triumphal-arch entrance. More significantly, the building is set on a terraced knoll ascended by four sets of broad marble stairs with wide abutments. "Long rows of trees, uniformly planted," [50] line both sides of the

approach, originally a reflecting pool that was drained by 1930. Although the rows of trees are situated below the terraced stairs, the entire arrangement recalls Pope's landscape treatment for the Lincoln Memorial Building. [51]

POPE'S LINCOLN MEMORIAL BUILDING

For the design of the Memorial Building itself, Pope fashioned a compromise between his original museum building and a more intimate, memorial structure, rejecting altogether the idea of an adjacent memorial column for the cabin site. Pope created a hybrid structure that operated as both an exhibition space and a memorial to the birth place of Lincoln, specifically, a memorial to the rude log cabin of his birth. Rather than plan a formal museum, Pope's revised plan called for one large "Exhibition Room" that left enough space for the cabin and interior pedestrian space to surround it.

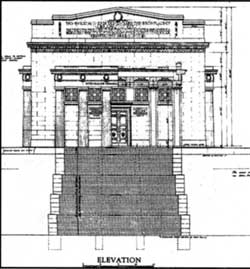

The Memorial Building measures fifty by thirty five feet and encloses a single chamber. Constructed of pink Stony Creek granite and reinforced concrete, the building is set on a low terrace and oriented to the south. [52] The main, or south facade, features a shallow hexastyle Doric portico with responds and wreaths in place of triglyphs in the frieze. Above the portico, a bold, dentil cornice continues around the building. The hip roof is set behind a stepped, gabled parapet, and a band of five windows with neo-classical granite grilles is situated above the double bronze doors of the main entrance. Passages from Lincoln's speeches are incised in the walls that flank the main en trance and on the entablature of the portico. Five lines articulating the purpose of the memorial are incised in the parapet above the portico (see Appendix A). [53]

The identical east and west elevations feature engaged, tetrastyle Doric porticos, employing the same wreath motif as the main facade. Three windows set between the columns include granite grilles that are taller than the square windows above the main entrance. The flat parapets give these elevations a rectangular profile. [54] The rear elevation maintains the symmetry of the main facade but without a portico; a band of five square windows is situated above double bronze doors. A recessed, rectangular panel is located above the windows with similar vertical panels placed be neath each window. Bronze plaques denoting the history of the memorial and board of trustees of the LFA are mounted on the panels that flank the rear entrance. [55]

The birth cabin is located behind bronze stanchions in the center of the Memorial Building. Its rectangular plan is outlined with inlaid pink marble with crosset corners, contrasting with the herringbone brick floor. [56] Above the pink marble dado, pilaster crosset surrounds frame each of the sixteen windows. Additionally, light was originally provided by a skylight incorporated into the hip roof In 1959, electric lighting was installed in the ceiling, and the glass panes that transmitted natural light were replaced with translucent plastic panels that conceal the fluorescent lighting. [57] A ring of sixteen ceiling coffers with plaster rosettes, based on those found in the Pantheon in Rome, surround the translucent panels. [58]

In creating a shrine for the Lincoln birth cabin, Pope was asked to devise a building type a building to house a building—for which there were few celebrated examples. [59] Nonetheless, structures contemporary to the period and notable buildings from antiquity clearly influenced his final design. For the basic requirement of enshrining the cabin, he turned to the mausoleum, a structure designed to hold a static object and requiring limited building services. In the United States, mausolea did not appear as public memorials until after the Civil War, with the first three significant monuments constructed in the two decades preceding the Lincoln memorial: the Garfield Memorial, Cleveland, Ohio, 1885-89; the General Grant Monument, New York City, 1891-1897; and the McKinley National Memorial, Canton, Ohio, 1905-07. Richard Lloyd Jones, secretary of the LFA, wrote of "the stately tombs we have erected to Grant and McKinley," compared with the "modest tribute" planned for Lincoln. Pope's design, described as a temple in the popular literature of the period, borrows heavily from the Grant and McKinley tombs. [60]

At the time of its completion, the Grant Monument, popularly known as Grant's Tomb, was comparable in scale and cost to only two American memorials, the Washington Monument and the Statue of Liberty. [61] Like so many architectural revivals, the monument, designed by John H. Duncan, is loosely based on the fourth-century-B.C. tomb of Mausolus. [62] The Grant Monument contains three parts: a high base or podium that contains the sarcophagi of President and Mrs. Grant and Civil War artifacts; a peristyle drum; and conical dome. It is the podium, however that may have served as the model for Pope's Memorial Building. Roughly twice the size of Pope's building, the podium features a hexastyle Doric portico on the main facade, four engaged Doric columns on the side elevations, and, unlike the Memorial Building, an apse at the rear. The fenestration, cornice, parapet, and many of the decorative elements are equally similar, although Pope's design does not include sculptural figures on the parapet. [63]

The basic shape and profile of Pope's Memorial Building also turned to earlier building designs, most fundamentally the famous temples of Greece such as the Temple of Aphaia and the Parthenon of the Acropolis. The most recent biographer of Pope, Steven McLeod Bedford, notes how the Memorial Building "immediately evokes images of Leo von Klenze's Walhalla," [64] furthering the notion of Pope's debt to both the classical revival of the time and, more important, the architecture of Classical Greece. Such direct association with Greek temples was both expected and appropriate for the memorialization of such an emotionally and historically potent site as the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln. Pope's use of classical architecture was direct and unabashed, and his use of the site to duplicate ancient rites such as ceremonial pro cession and deity (cabin) worship is clearly evident in the plan of the Memorial Building and its immediate grounds.

On November 9, 1911, three thousand people gathered at the foot of the Memorial Building for the dedication of the Lincoln Birth place Memorial. [65] President William Howard Taft, a member of the LFA Board of Trustees, delivered an address. But what was to be the "Nation's Commons, the meeting-place of North, South, East and West," [66] was rapidly eclipsed by plans to erect a Lincoln memorial in Washington, D.C. Congress approved funds for the Lincoln Memorial on February 9, 1911, and the nation's attention quickly turned to this latest addition to the Mall. [67] Articles with the proposed design by Henry Bacon appeared in popular literature and architectural journals, while little mention was made of the completion of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial. [68]

|

| ||||

|

|

|

| Figure 46: The Memorial Building and designed landscape as it appeared several years after the 1911 dedication. Note the replanted poplars and hedges along the stairway. |

INTEGRITY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES

The properties eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under this context exhibit all aspects of integrity: location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association. Alterations made to the Memorial Building, including a new roof and HVAC systems, have had a minimal effect upon its historic design, materials, and workmanship. Similarly, the memorial steps, an integral part of the design, have been altered with the introduction of limestone benches and paved landings but retain much of their historic appearance. Although elements of Pope's landscape design remain, the areas surrounding the Memorial Building largely reflect the activity of the War Department from 1916 to 1933. However the memorial plaza, walkways, Sinking Spring, and other structures developed by the War Department do not diminish the ability of the Memorial Building to convey its historic significance.

CONTRIBUTING RESOURCES

Memorial Building and Steps (1909-1911)

Birthplace Cabin (1809-1911)

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| |||||

NOTES

1. Damie Stillman, "Death Deified and Honor Upheld: The Mausoleum in Neo-Classical England," Art Quarterly 1(1978): 177-78.

2. Howard Colvin, Architecture and the After-Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 330-31.

4. Stillman, 196; Colvin, 339.

6. Robert L. Alexander, "The Public Memorial and Godefroy's Battle Monument, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 17 (March 1958): 22.

8. David M. Kahn, "The Grant Monument," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 41 (October 1982): 215.

11. Neil Harris, The Artist in American Society: The Formative Years, 1790-1860 (New York: George Braziller, 1966), 190.

14. The Lincoln Farm Association attempted a similar fund-raising effort in which donations for the construction of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial could not exceed twenty-five dollars. It also resulted in disappointing returns.

15. Pamela Scott, "Robert Mills and American Monuments," in Robert Mills, Architect, John M. Bryan, ed. (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects, 1989), 161-62.

22. Stillman, 196; Colvin, 340

24. See Leland M. Roth, McKim, Mead and White, Architects (New York: Harper and Row, 1983), 136-38.

25. William Judson Hampton, Presidential Shrines from Washington to Coolidge (Boston: Christopher Publishing House, 1928), 65-66.

26. John Zukowsky, "Monumental American Obelisks: Centennial Vistas," Art Bulletin 58 (December 1978): 576-78; Ferris, 417-20.

29. Stephen Bedford, "Early Monumental Work," chapter draft (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1992), 10.

30. "The Lincoln Birthplace Farm," Collier's Weekly 38 (February 7, 1907): 16-17.

31. Quoted in Steven McLeod Bedford, John Russell Pope, Architect of Empire (New York: Rizzoli, 1998), 10.

32. Herbert Croly, "The Recent Works of John Russell Pope," The Architectural Record 29 (June 1911): 442.

33. Arthur Drexler, ed., The Architecture of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1977), 82, 86-87.

34. Richard Chaffee, "John Russell Pope," Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects Vol. 3 (New York: Free Press, Macmillan Publishing, 1982), 450; Joseph Hudnut, "The Last of the Romans: Comments of the Building of the National Gallery," Magazine of Art 34(1941): 169-73.

35. 151 Fredrick Koeper,American Architectures Volume 21860-1976, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 289-291.

36. Richard Chaffee, "John Russell Pope," Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects Vol. 3 (New York: Free Press, Macmillan Publishing, 1982), 450; Joseph Hudnut, "The Last of the Romans: Comment of the Building of the National Gallery," Magazine of Art 34 (1941): 169-73.

37. William L. McDonald, quoted in Bedford, 8.

38. Bedford, 10; Richard Lloyd Jones, "The Lincoln Centenary," Collier's Weekly 40 (February 15, 1908): 12-13.

39. Jones, February 15, 1908,12-13.

43. Roth, 247-50. It should be noted that Pope eventually erected a monumental column, the Meuse-Argonne Monument near Montfaucon, France, 1926-34, which is derivative of White's Ship Martyrs' column in both style and setting. See Elizabeth G. Grossman, "Architecture for a Public Client: The Monuments and Chapels of the American Battle Monuments Commission," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 43 (May 1984): 119-43.

44. The Senate Park Commission was composed of Daniel H. Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., Charles F. McKim, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Lowry, 82-88; Roth, 254.

45. Jones, February 15,1908,12-13.

47. Pope, "Memorial Building Plans."

48. Pope, "Terrace Stairs" and "Block Plan."

51. See Edward Thornton Heald, The William McKinley Story (Stark County Historical Society, 1964), 123-24; Hampton, 213-17; Ferris, 507-9.

52. Pope refers to the main facade as the south elevation although the building is actually oriented to the southeast.

53. Pope, "S. Front Elevation."

57. Center for Architectural Conservation, College of Architecture, Georgia Institute of Technology, comp., Historic Structures Assessment Report: Lincoln Birthplace Memorial Building (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, Park Historic Architecture Division, 1991), 4. A second significant alteration to the building includes the installation of terrace steps on the east and west sides by the War Department in 1930 (G. Peterson, 52).

58. Bedford, 12; Pope, "Main Floor Plan." Similar granite rosettes adorn the ceiling of the south portico.

59. In 1896, the Grant birth house was enclosed in an unimposing masonry and steel memorial building on the Ohio State Fairgrounds in Columbus. See Hampton, 160-62.

60. Direct influence from antique sources cannot be discounted because Pope traveled extensively in Greece and Italy. In terms of building type, Pope's design is related to the Roman mausolea, such as the second century tomb of Annia Regilla on Rome's Appian Way with its single-cell plan, high windows, and vertical proportions. "A National Shrine," Bulletin of the Pan American Union 43 (October 1916): 498; Tarbell, 95.

62. Pope's Temple of the Scottish Rite is also based on the tomb of Mausolus and more closely reflects the supposed ancient appearance of the tomb.

63. See Kahn, 226-31; Hampton, 163-64; Ferris, 475-79.

67. In February 1912, Pope was asked to submit designs for the Lincoln Memorial, and he again turned to funerary architecture for design sources. Three of his seven alternate proposals feature fantastic pyramid forms: a smooth-sided pyramid with four temple-front entrances; a Meso-American pyramid; and a ziggurat.

68. For the Lincoln National Memorial see, "What Shall the Lincoln Memorial Be?," American Review of Reviews 38 (September 1908): 334-42; Leila Mechlin, "The Proposed Lincoln Memorial," Century Magazine 83 (January 1912): 368-76; "The Proposed Lincoln National Memorial," Harper's Weekly 56 (January 20, 1912): 21; and "The Lincoln Memorial: The Man and the Monument," The Craftsman 26 (April 1914): 16-20. For the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial see "The Lincoln Centennial Celebration," American Review of Reviews 39 (February 1909): 172-73; and "A National Shrine," 496-501.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

abli/hrs/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2003