|

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace

Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter Two:

LINCOLN COMMEMORATION AND THE CREATION AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN BIRTHPLACE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE, 1865-1935

NATIONAL LINCOLN COMMEMORATION, 1865-1922

The growing veneration of Lincoln in the half century after his death, which resulted in the 1911 dedication of a memorial at his birthplace, had a number of sources. The first assassination of an American president, coming on the heels of a bloody Civil War, shocked the American public. In the highly emotional atmosphere of spring 1865, Americans began the apotheosis of Lincoln. The martyred president personified the self-sacrifice, idealism, and resoluteness that had preserved the republic through four years of war. The postwar decades then brought sweeping changes—Reconstruction of the South, industrialization, mechanization, urbanization, and increased immigration—that profoundly altered traditional patterns of American life. One response to this torrent of change was a romantic idealization of the past, especially the supposedly simpler, purer agrarian life. Lincoln's frontier upbringing exemplified this largely bygone rural way of life. Additionally, the self-reliant, self-made man was an idol of the postbellum age, and Lincoln was an example in politics as much as Andrew Carnegie was in industry. Finally, the years between 1875 and 1890 brought numerous centennial celebrations of the nation's founding. [1] These centennials helped engender an enhanced regard for the past and resulted in efforts to create memorials to, and preserve sites associated with, famous Americans.

LINCOLN'S IMAGE IN THE POSTWAR PERIOD

The near deification of Lincoln began almost immediately after his death. [2] Already exhausted by the trials of the Civil War, Americans vented their emotions following Lincoln's assassination in an "orgy of grief." [3] Lincoln quickly became the symbol of the nation's sacrifices during the war. The controversies surrounding Lincoln's conduct of the war and the virulent personal attacks on him were forgotten, and Americans celebrated his idealism, fairness, compassion, devotion to duty, and vision of the future. Lincoln was compared to George Washington and praised as the second savior of the republic. Clergymen and others stressed Lincoln's Christ-like attributes; details of Lincoln's life an obscure birth, a carpenter father, and assassination on Good Friday inevitably reinforced the connection. [4]

Linked by telegraph, newspapers, and mass-circulation weeklies, millions across the North participated in the protracted mourning over Lincoln that included thousands of local memorial services featuring orations and eulogies, commemorative poetry, and a ceremonial funeral trip. After lying in state in Washington, Lincoln's remains were carried on a special train on a two-week journey back to Springfield. As a symbolic gesture, the train reversed the route Lincoln took to Washington in 1861. In Baltimore, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, New York, Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, and Chicago, Lincoln's casket was removed from the train and placed on a black-draped catafalque. Hundreds of thousands filed past the casket while choirs sang hymns and church bells tolled. The train slowed to five miles per hour at dozens of smaller places to allow assembled citizens to pay their respects. [5]

|

| Figure 8: Engraving entitled Abraham Lincoln the Martyr Victorious by John Sartain, 1865 |

Walt Whitman's 1865 poem, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd," which lauded Lincoln as "the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands," was one of hundreds of verse tributes. [6] Herman Melville, Julia Ward Howe, William Cullen Bryant, James Russell Lowell, and Oliver Wendell Holmes also wrote memorial poems. An entire volume of Poetical Tributes (1865) included the work of poets from all the northern states, seven southern states, and three foreign countries. Letters of the period routinely referred to Lincoln as the "Great Emancipator" or the "Great Martyr." [7]

Biographical treatments abetted the apotheosis of Lincoln. Two themes emerged in Lincoln biographies following his death. One took its cue from the eulogies and emphasized Lincoln's high principles and saintliness; the other stressed his backwoods western origins. Josiah G. Holland's depiction of Lincoln as a martyr-saint endowed with all the Christian virtues, contained in his 1866 Life of Abraham Lincoln, proved immensely popular; the book sold more than 100,000 copies. In Holland's view, Lincoln was a model youth who rose on the strength of his merit and high ideals. Holland characterized Lincoln as "savior of the republic, emancipator of a race, true Christian, true man." [8] The portrayal of Lincoln as a combination of Christ and George Washington was echoed in dozens of other nineteenth-century biographies. [9]

Disgusted by the popularity of a sentimental, idealized view of Lincoln, William H. Herndon, Lincoln's friend and his law partner from 1844 to 1861, devoted himself to presenting a more down-to-earth portrait. Herndon did a vast amount of research to supplement his personal recollections, combing court records and interviewing and corresponding with dozens of persons in Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky. Herndon leased his research materials to Lincoln's friend and sometime bodyguard Ward H. Lamon for Lamon's 1872 Life of Abraham Lincoln, largely ghost written by Chauncey Black. After many delays, Herndon's Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life, written in collaboration with Jesse Weik, appeared in 1889. Both Lamon and Herndon emphasized the ambitious, folksy, irreverent, story-telling Lincoln: a true son of the western prairie. Herndon was most reliable on events he witnessed; he did not critically evaluate material supplied by others. Although Herndon's book sold poorly, his portrait had a lasting impact on the popular conception of Lincoln. [10] Toward the end of the nineteenth century the two images of Lincoln began to merge into a composite. Lincoln became the embodiment of an American ideal that combined frontier earthiness and Christian virtue, shrewdness and saintliness, ambition and nobility of soul. [11]

POSTWAR AMERICAN ROMANTICISM

Lincoln's heroic reputation contrasted sharply with the materialism, corruption, and generally undistinguished political leadership of the postwar decades. Characterized variously as '"The Gilded Age," "The Age of Excess," and the "Great Barbecue," the 1865-1890 period was one of great economic and social upheaval, unprecedented extremes of wealth and poverty, and widespread political corruption. Many of the changes associated with the postwar years were well underway when Lincoln died. The huge northern Civil War armies had required a rapid expansion of industry and financial institutions, and graft in wartime supply contracts foreshadowed later scandals. Rapid industrialization continued after the war, and America changed from a nation of small, isolated, rural communities to a more urban-oriented and economically and culturally unified country. This transformation was largely the result of transportation and communication advances: a transcontinental rail net, improved telegraphs, mass-circulation periodicals, and the telephone. America was also becoming more crowded; the population more than doubled from 36 million in 1865 to 76 million in 1900. [12]

Industrialization and the growing mechanization and commercialization of agriculture increased American wealth and changed the character of American life. Industrial production rose by 1200 percent between 1850 and 1900, while farmers increasingly shifted from subsistence crops to marketable staples like wheat, corn, cotton, and tobacco. Laissez-faire was the ruling economic philosophy, and most policies of the national Republican and Democrat parties on tariffs, railroads, banking, and immigration encouraged industrial expansion. Individuals amassed huge fortunes from railroads, iron and steel, textiles, food processing, petroleum, and financial manipulation. [13] Broad segments of the public lionized the self-made industrial tycoon, exemplified by Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish immigrant who rose from bobbin boy in a textile mill to presidency of the largest American steel producer. Carnegie and other millionaires combined philanthropy with lavish spending on fine houses and ostentatious entertaining. [14]

Urbanization and increased immigration accompanied industrial growth. Before the war, cities had been largely mercantile centers; postwar urban growth was tied to industrial expansion. The number of cities of 100,000 or more inhabitants rose from nine in 1860 to fifty in 1910. By 1900, one-third of the population was classified as urban, i.e., living in cities of 8,000 or more. The cities attracted millions of European immigrants. By the 1890s, the sources of immigration had largely shifted from Great Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia to southern and eastern Europe. Although some immigrants farmed, the majority congregated in urban areas, taking low-paid industrial and service jobs. Many native-born Americans found the religion, customs, and appearance of these new immigrants alien and grew anxious over the changing ethnic make-up of the country. [15]

Postwar politics were characterized by intense partisanship, an absence of idealism and strong leadership, and substantial graft. In 1905, historian Henry Adams observed that "One might search the whole list of Congress, judiciary, and executive during the twenty-five years 1870 to 1895, and find little but damaged reputation." [16] Governmental corruption reached a nadir in the 1870s. The Democrat Tweed Ring, led by New York Mayor William M. Tweed, looted as much as $100 million from the public treasury between 1868 and 1871. One scandal after another implicating cabinet secretaries and White House staff marred President Grant's administrations (1869-1877). Throughout the postwar period, some Republicans traded on the memory of Lincoln for political gain. A succession of relatively weak postwar presidents only added luster to Lincoln's image. [17]

As an antidote to the economic, social, and political upheavals of the postwar decades, many Americans sought escape in sentimental romances. Romances took many forms: there was the romance of the self-made man celebrated in Horatio Alger's many novels and the romance of exotic times and places, exemplified by the phenomenal popularity of novels like Ben-Hur (1880). In a country increasingly national, urban, industrial, and class-stratified, millions viewed the local, agrarian, seemingly egalitarian American past through the mists of sentiment. As historian Robert H. Wiebe has put it, "the peculiar ethical value of an agricultural life, long taken for granted by so many Americans, now became one of their obsessions." [18] Beginning in the 1880s, highly romanticized depictions of the antebellum South, the Colonial period, the frontier, and rural life frequently appeared in popular novels and poems. [19]

The allegedly wholesome, self-sufficient pioneer experience exemplified by Lincoln's early life was a popular theme in fiction. James Allen Lane's novel, The Choir Invisible (1897), the saga of an eighteenth-century Kentucky schoolmaster, sold more than 250,000 copies. Lincoln himself appeared as a character in historical novels as early as 1888 (The McVeys and The Graysons). As the centennial of Lincoln's birth approached, fictional treatments multiplied. Lincoln was a central character of The Crisis (1901), a historical romance by Winston Churchill that sold one million copies. Fictional depictions of Lincoln followed the biographies, emphasizing the upright backwoods lawyer and the wise wartime president. [20]

|

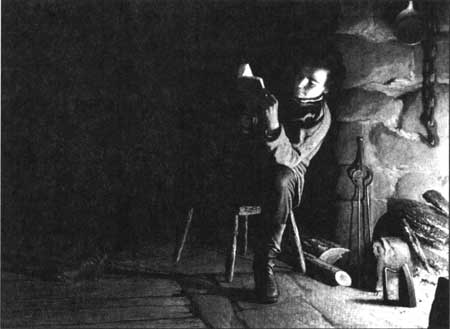

| Figure 9: Painting entitled Boyhood of Lincoln by Eastman Johnson, 1868 |

The log cabin was an object of special veneration in romanticized depictions of frontier life. Birth in a log cabin became associated with the positive qualities of simplicity, egalitarianism, democracy, self-sufficiency, and upward mobility. The log cabin was a symbol of the unlimited possibilities for advancement considered inherent in American life. The log cabin made its first appearance as a political symbol in General William Henry Harrison's successful presidential campaign in 1840. On the Whig ticket that year were Harrison, the hero of the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, and John Tyler. An opposition newspaper's derogatory comment about General Harrison's alleged willingness to sit in his cabin drinking hard cider while collecting a pension was converted into a major campaign theme. Famous for the slogan, "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too," the 1840 Whig campaign adopted a populist tone and featured the image of the log cabin on floats, badges, books, quilts, and glass plates. [21]

Lincoln exhibited ambivalence about his log cabin background; he realized its political attractiveness to western voters, but almost never spoke of it to friends. In the 1860 presidential election, the Republican Party borrowed a page from the Harrison campaign, touting Lincoln as a prairie-bred man of the people. To Lincoln's embarrassment, his party promoted him as "Honest Abe, the Rail-Splitter." Campaign literature emphasized Lincoln's obscure birth in a log cabin and his pioneer upbringing, reinforcing the popular association of the log cabin with democratic virtues. [22]

|

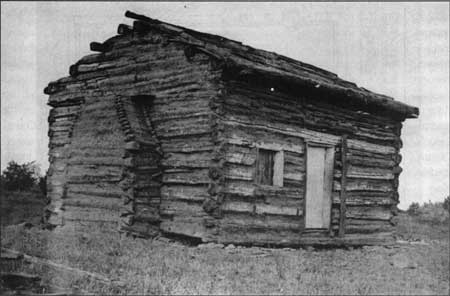

| Figure 10: A circa 1890 photo of the "Goose Nest Prairie Cabin" in Illinois. This was one of several log cabins associated with the early life of Abraham Lincoln. |

The adulation of Lincoln in the later nineteenth century coincided with increased interest in historic preservation and commemoration. George Washington and Lincoln, linked in the public mind as, respectively, the father and savior of the nation, were the focus of a number of preservation efforts. One of the earliest American historic preservation efforts was the 1850s campaign to make a national shrine of George Washington's house, Mount Vernon. This campaign was the work of a private group, the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, which purchased the house and two hundred acres in 1858. In the same year, the State of Virginia accepted the gift of a small tract that included the former site of Wakefield, Washington's birthplace in Westmoreland County, Virginia. In 1882, the state donated the property to the Federal government, which erected a granite obelisk commemorating Washington's birth in 1895-1896. [23]

Another event that revived interest in the American past was the Centennial Exposition, held in Philadelphia from May to November 1876, to mark the one-hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The centennial year provided an occasion for Americans to re-examine their history. The events of the Revolutionary period received great attention, and a re-created Colonial house was a popular exhibit at the exposition. Many of the eight million exposition visitors went away with a new interest in, and enthusiasm for, the American past. This greater historical appreciation manifested itself in efforts to preserve Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Washington's headquarters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, the powder magazine at Williamsburg, Virginia, and Andrew Jackson's Tennessee home, the Hermitage. [24] Campaigns to preserve historic sites associated with Lincoln's life began in the 1880s.

EARLY LINCOLN COMMEMORATION

|

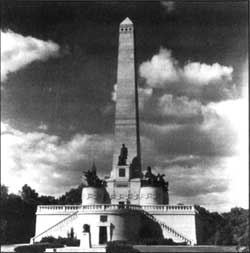

| Figure 11: Figure 11. Lincoln National Monument, Springfield, Illinois. Designed by Larkin G. Mead, 1874 |

The first major Lincoln commemorative project to be completed was his tomb in Springfield. In April 1865, a group of Illinois residents formed the National Lincoln Monument Association to plan Lincoln's burial in Springfield. At Mrs. Lincoln's request, suburban Oak Ridge Cemetery was selected as the site of the tomb. Larkin G. Mead, a Vermont sculptor, won an 1868 design competition sponsored by the association, and work on the tomb began the following year. Lincoln's remains were placed in the tomb in September 1871, and the tomb was dedicated in October 1874, upon the completion of Mead's bronze statue of Lincoln. Between 1877 and 1883, four bronze military groups representing the infantry, artillery, cavalry, and navy were added to the base. In 1895, the National Lincoln Monument Association donated the tomb to the State of Illinois. To correct foundation problems, the state rebuilt the tomb in 1900-1901, adding 37 feet to the height of the obelisk. [25]

The Federal government acquired Ford's Theatre through legislation enacted April 7, 1866, to prevent any inappropriate use of the assassination site. The government used the building for offices and storage until 1932, when it was converted to a museum displaying Lincoln memorabilia. The building was transferred to the National Park Service August 10, 1933. The NPS restored the theatre to its 1865 appearance in the 1960s, reopening it for theatrical performances and tours in 1968. The site was redesignated the Ford's Theatre National Historic Site in 1970. [26]

A number of American cities erected commemorative Lincoln statues between 1868 and 1900. Three statues were unveiled in Washington, D.C., in Judiciary Square (Lot Flannery, 1868), the Capitol Rotunda (Vinnie Ream, 1871), and Lincoln Park (Thomas Ball, 1876). Other notable Lincoln sculptures appeared in Brooklyn (Henry K. Brown, 1869), New York City (Henry K. Brown, 1870), Philadelphia (Randolph Rogers, 1871), and Chicago (Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1887). Typically, these monuments featured a bronze statue mounted on a pedestal. Congress appropriated funds for the statue in the Capitol; private subscriptions or bequests paid for the other works. [27]

|

| Figure 12: Figure 12. Freedmen's Monument, Washington, D.C., by Thomas Ball, 1876 |

During the 1880s and 1890s, Lincoln's home of seventeen years in Springfield and the house in Washington where he died became historic sites open to the public. In 1883, Osborn H. Oldroyd, a collector of Lincoln memorabilia, rented Lincoln's home in Springfield and opened it to the public as a museum. Lincoln's son Robert Todd Lincoln in 1887 conveyed the house to a board of trustees established by the State of Illinois. The state maintained the site until Congress authorized the Lincoln Home National Historic Site on August 18, 1971. In 1892, the private Memorial Association of the District of Columbia rented the Petersen house on Tenth Street where Lincoln died. Congress authorized the House Where Lincoln Died National Historic Site on June 11, 1896; it was consolidated into the Ford's Theatre National Historic Site on June 23, 1970. [28]

Surprisingly, no monuments to Lincoln other than statues were raised in the nation's capital in the nineteenth century. Of the three statues that were dedicated, however, the Freedmen's Monument by Boston sculptor Thomas Ball is notable for being funded mostly by African Americans, many of whom had served with Black regiments during the Civil War. [29] Dedicated in 1876, the statue depicts a benevolent Lincoln, his left arm outstretched over a slave rising from a kneeling position. In his other hand Lincoln holds the proclamation itself Explicitly adopting the theme of "the great emancipator," the statue's unveiling was accompanied by a speech from Frederick Douglass who tactfully noted that the slave's emancipation was not wholly the result of Lincoln's morality, love, and grace, but was also driven by political imperatives. [29] Douglas likely was trying to temper the statue's overtly paternalistic imagery of Lincoln and the kneeling slave with the less romantic realities of emancipation and reconstruction.

As early as 1867, Congress authorized a Lincoln Memorial Association to raise private funds for a monument in Washington, D.C. Nothing resulted from this effort or from numerous other proposals and bills introduced through the rest of the century. The pace of commemorative activity quickened as the 1909 centennial of Lincoln's birth approached. In 1901, the U.S. Senate established a commission (known as the McMillan Commission in honor of its principal sponsor, Michigan Senator James McMillan) to prepare a comprehensive city plan for the capital. Commission members were architects Daniel Burnham and Charles F. McKim, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. A key recommendation of the 1902 McMillan Commission Plan was for a Lincoln memorial to be erected on reclaimed marsh land at the western end of the Mall on axis with the Capitol and the Washington Monument. Congressional authorization for the memorial finally came in 1911, and the Greek-temple form Lincoln Memorial, designed by architect Henry Bacon, was dedicated in 1922. [30] Significantly, proposals for a Lincoln memorial in Washington were being debated in the same years that the Lincoln Farm Association was promoting its plan for a memorial at the birth farm in Kentucky.

COMMEMORATING LINCOLN IN KENTUCKY, 1895-1935

Efforts to commemorate Lincoln in Kentucky lagged behind those occurring in other states, such as Illinois and New York, and in Washington, D.C. Ambivalent feelings toward Lincoln and the Union, during and immediately after the war, likely stifled within the state the kind of emotional and monumental tributes that northern populations exhibited following the assassination. However, as the Lincoln Centennial approached, commemorative efforts in Kentucky stirred. Both local and outside interests pursued commemorative ventures in the state; commercial profitability inspired some efforts, and others represented patriotic fervor and admiration for a venerated public figure.

In summer 1861, Kentucky occupied an awkward position in the Union. As one of three border states, Kentucky shared many traits with its Confederate neighbors. Kentucky's population was large, totaling over 1.15 million, and included about 220,000 slaves. This large population in a southern alliance could have greatly benefited the Confederacy, which fought against a much larger northern populace. Lincoln recognized Kentucky's strategic geographical importance and the potential for a southern alliance due to the state's agricultural economy and dependence on slave labor. Lincoln also knew that Kentucky voters had not generously supported his presidential bid. [31]

After Sumter and southern secession, Kentucky claimed neutrality. Lincoln agreed to honor this position even though he knew that Kentucky allowed Confederate goods to be channeled through the state to Tennessee, an action that nullified the state's neutrality. In an effort to win the support of Kentucky, Lincoln ignored these activities. However, after the August 1861 state elections revealed strong Unionist support, Lincoln vigorously enforced pro-Unionist policies and banned all trade with the Confederacy. Shortly thereafter, the Union flag flew over the state capitol and many southern supporters, including the governor, left the state. Ultimately, Kentucky loyalties remained split throughout the war, although politically, the state sided with the north. By war's end, Kentucky had sent over 40,000 men to the Confederacy and 100,000 men had fought for the Union. [32]

Lincoln maintained many ties to Kentucky, both emotionally and physically, throughout his life. Although the Lincoln family had left Kentucky over forty years before the war, many Kentuckians had settled southern Illinois; Lincoln's wife was Kentuckian by birth; and several close Lincoln associates, including his good friend Joshua Speed, were Kentuckians. [33] However, the lengthy and brutal war likely diminished what sympathies Kentuckians felt toward their renowned son immediately after the war. The state's ties to Lincoln had weakened over a period of more than forty years. For Kentuckians, events occurring during Lincoln's adult life both strengthened pro-southern loyalties and forged political and emotional alliances with the Union leader. With this mixed political climate, public and private commemorative efforts for Lincoln failed to emerge until the twentieth century. Unlike most of the South, Kentucky eventually raised several statues and a monumental building and fostered Lincolnian tourism recognizing, beyond sectionalism, the man's national importance.

Following the assassination, local residents directed Lincoln admirers to the Sinking Spring Farm and indicated the knoll where the Lincoln cabin had stood. However, because time had lapsed, and interest had waned between 1811 and 1865, few LaRue County residents personally remembered the Lincolns or their homestead. One sojourner, John B. Rowbotham, an illustrator for a Cincinnati publisher, visited the Sinking Spring Farm in 1865 and wrote about his experience to William H. Herndon. Rowbotham traveled by rail to Elizabethtown and then by coach to Hodgenville. From Hodgenville, the old Lincoln farm lay three miles south on a "good, straight road." Rowbotham sketched the chimney rubble on the knoll that county residents claimed marked the site of the former Lincoln birth cabin. [34]

In 1894 and 1895, interest in the Lincoln birthplace rekindled. The first attempt to memorialize the farm occurred in 1894, when a Major S.P. Gross made a bid to purchase the property, sans cabin. [35] Gross wanted to establish a national historic site that would preserve the Lincoln birthplace just as similar efforts at Mount Vernon and the Hermitage preserved sites linked to other national leaders. [36] However, Gross's plan never materialized, and another interested party stepped in. Alfred W. Dennett, a New York restaurateur, bought the Sinking Spring Farm, also known as the Old Creal Place, from Richard Creal.

|

| Figure 13: Figure 13. The Sinking Spring Farm as it appeared in 1895 |

Dennett purchased the property, November 23, 1894, with some very specific motives. But whether Dennett's ultimate scheme represented nineteenth-century hucksterism, or simply a personal desire to raise funds for urban religious missions, is unclear. Dennett was a religious man, cofounding the Florence Crittenton Missionary, for wayward women, and other urban missions throughout the country. Dennett purchased the former Lincoln farm through his local agent, James W. Bigham, a prominent Methodist preacher and evangelist, known throughout western Kentucky in the 1890s. Dennett made no excuses for purchasing the property. He intended to build a hotel and park on this historic spot for commercial purposes. As an immediate goal, Dennett hoped to persuade a national Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) encampment, scheduled to meet in Louisville in fall 1895, to visit his property. By charging an admission fee, Dennett sought to regain his original investment. In August 1895, Bigham claimed that Dennett instructed him to find and reconstruct the original Lincoln birth cabin associated with the property. Bigham purchased a cabin located on the farm of John A. Davenport, one mile north of the Sinking Spring Farm. Then, he and his son dismantled the Davenport cabin and used the logs to erect a cabin on the Sinking Spring Farm in November 1895. [37]

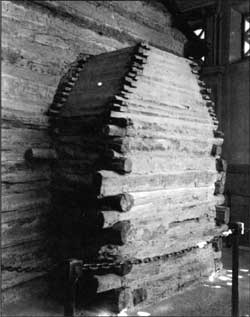

The authenticity of the cabin erected by Bigham in 1895,86 years after Lincoln's birth, has been fiercely debated. Bigham's authentication story, promoted in his "lecture, historic & descriptive," rested on the premise that the birth cabin was removed from its original site prior to the end of the Civil War. Bigham relied on a supposed tradition that a LaRue County physician, Dr. George Rodman, returned from a visit with Lincoln in Washington, circa 1861, filled with admiration for the president. Wanting to honor Lincoln, Rodman purchased the birth cabin from Richard Creal and moved it to his farm. Later investigators have found at least three major problems with this authentication: in all probability, it was Dr. Jesse Rodman, George's brother, who visited Lincoln; Richard Creal did not own the Sinking Spring Farm until 1867; and neither Rodman brother ever owned the property to which the cabin allegedly was moved in 1861. [38]

The Davenport cabin purchased by Bigham was described in some testimony as a two story log residence. When Bigham re-erected the cabin on the Lincoln farm from the neighboring Davenport farm, he constructed a one-story cabin, approximating the sixteen by eighteen foot dimensions of traditional, one-room, Kentucky log cabins. [39] Bigham also erected a partial stick chimney. The cabin chinking was mud and the gabled roof consisted of log purlins with wood planks. A central door and one unglazed window opening faced east. Bigham situated the cabin on the knoll above the Sinking Spring that some accounts identified as the traditional cabin site. [40] Bigham finished erecting the cabin just in time for the GAR encampment.

|

| Figure 14: The "Davenport Cabin" as assembled by James W. Bingham in 1895 |

Fewer than 100 soldiers from the GAR encampment, which attracted an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 participants, visited the Sinking Spring Farm. The exorbitant admission fee and railroad fare proposed by Bigham and the deliberate commercial exploitation of the Lincoln farm incensed many of the veterans. [41] For the next two years, little happened at the farm. In 1897, Bigham dismantled the alleged Lincoln cabin and exhibited it, with another equally suspicious cabin described as Jefferson Davis's birthplace, for a price on the midway at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in Nashville. [42] The Nashville venture proved a poor investment for Dennett, but he agreed to contract with Bigham for future exhibitions of the cabins and for the sale of souvenirs. However, by August 1899, after a failed attempt to sell the Sinking Spring Farm to Congress, Dennett stored the Lincoln and Davis cabins' logs in the basement of a New York City Bowery mission he operated. [43]

In late 1898 and early 1899, financial problems plagued Dennett in both New York and California, and he may have stored the cabins to protect his investment. Without notifying Bigham, Dennett conveyed the Lincoln farm property and the log cabins to David Crear, a friend to whom Dennett was indebted. However, Dennett continued to pay taxes on the farm, attempted to sell the property, and retained Bigham as caretaker. [44] By 1901, Dennett concluded his relationship with Bigham and shortly thereafter contracted with Frederick Thompson and Ehner Dundy, two Nashville midway exhibitors, to rent the Lincoln and Davis cabins for display at the 1901 Pan American Exposition in Buffalo. Dundy and Thompson also later may have exhibited the cabins at a Coney Island amusement park they operated. Throughout this last period of exhibition, Crear appeared to hold legal possession of the cabins, but made no attempt to claim them. [45] By 1903, the midway showmen stored the logs in College Point, Long Island. However, in transit the cabin logs became mixed, and separating the two buildings proved difficult. [46]

After the logs had been in storage for several years, Thompson and Dundy publicly claimed ownership of the cabins through a series of newspaper articles. Also at this time, Crear filed suit to retain ownership of the farm that Dennett conveyed in 1899. However, the LaRue County Circuit Court decided that the Dennett conveyance to Crear was fraudulent and void. Dennett's attempt to liquidate his properties and clear some debts prior to bankruptcy proceedings proved unfortunate for Crear. The court ordered the Sinking Spring property sold at public auction and the proceeds distributed among Dennett's creditors. Richard Lloyd Jones, an editor for Collier's Weekly, bought the farm at auction, August 28, 1905, for $3,600. [47]

|

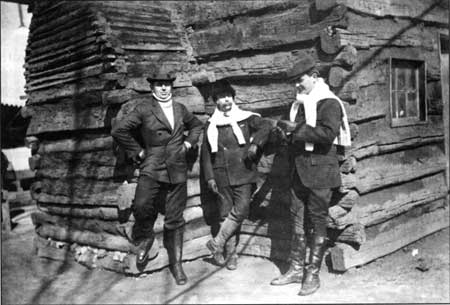

| Figure 16: Richard Lloyd Jones, Clarence Mackay, and Robert Collier of the Lincoln Farm Association stand in front of their cabin just prior to construction of the Memorial Building, 1909 |

Although New York parties dominated the cabin and farm transactions, Hodgenville recognized itself as the likely Kentucky candidate for a Lincoln birthplace tribute. Located approximately three miles north of the former Lincoln farm, the town recognized the advantages of that geographic link. Prior to the 1880s, Hodgenville competed with several other neighboring communities for commercial trade. The town witnessed greatest growth after a railroad line connected it to Elizabethtown in 1888. Between 1900 and 1905, Hodgenville flourished commercially. The town had two banks, five dry goods stores, four grocery stores, a hotel, two flour mills, three saloons, and a county jail. In 1903, Thomas Kirkpatrick, the Hodgenville postmaster, published a pamphlet, "Souvenir of Lincoln's Birthplace," to promote LaRue County Lincoln historical sites and the Hodgenville commercial district. In 1904, the Lincoln Monument Commission, authorized by the Kentucky legislature, sought subscriptions to finance a Lincoln memorial for the Hodgenville town square. [48]

The commission originally obtained a $2,500 appropriation to erect a tablet honoring Lincoln in the courthouse square. An appropriation from Congress accompanied by private contributions allowed the commission to augment their memorial with a statue. Adolph Alexander Weinman, a German native and pupil of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, won the commission. He produced a seated bronze Lincoln mounted on a marble base that was displayed in the Hodgenville square. Local women formed the Ladies Lincoln League to care for and promote visitation to Hodgenville's Lincoln statue. [49]

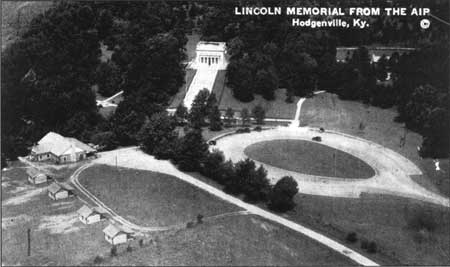

The town's fortunes rose after the statue's May 31, 1909, dedication. Tourism increased, and the town square grew in proportion. [50] Just three miles south of Hodgenville, the Lincoln Farm Association (LFA) began construction on a memorial building, which quickly overshadowed the Hodgenville effort. However, the pink granite and marble building erected by the LFA briefly catapulted obscure Hodgenville into the national limelight.

The LFA germinated in Richard Lloyd Jones's personal interest in Lincoln. In April 1904, Unity, a Chicago religious weekly edited by Jones's father, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, lamented Dennett's shameful neglect of the farm and commercial exploitation of the cabin. Richard Lloyd Jones, then managing editor of Collier's Weekly, enlisted the support of his employer, Robert Collier. Thus, financially supported, Jones traveled in 1905 to Hodgenville to investigate the property fully aware of Dennett's failing fortunes. Jones quickly retained a Hodgenville lawyer to advise him when the property might be available for purchase. In August 1905, Jones placed the winning bid at the public auction of the Sinking Spring Farm. In February 1906, Jones, through Collier's, announced the formation of the Lincoln Farm Association and solicited contributions to construct a Lincoln memorial at the farm. The LFA membership subscription cost as little as 25 cents and could not exceed $25.00. In this way, all Americans could contribute to the memorial fund. In its first drive to raise funds, the LFA, upon purchasing the "original" Lincoln cabin from Crear, commenced a cross-country railroad tour with the dismantled cabin. Unknown to the LFA, the logs they bought for $1,000 also contained many of the alleged Jefferson Davis cabin logs. Large crowds met the train in Pennsylvania and Indiana and viewed the logs before they were reassembled in Louisville's Central Park for the Kentucky Homecoming Week. [51]

When the LFA attempted to erect the Lincoln cabin in Louisville, it realized something was amiss. Because the Lincoln and Davis cabin logs were mixed by Thompson and Dundy, the Central Park cabin featured a rear entry, two doors, a mantle, and two windows. The logs bought by the LFA appeared to originate from three different sets: one marked by incised roman numerals, the second with black paint marks, and the third without marks. The cabin erected by the LFA at the Lincoln farm for the cornerstone laying ceremonies closely resembled that constructed by Bigham, with one central door and one window opening. The LFA added glass panes and muntins. The disposition of the additional logs is unknown. [52]

|

| Figure 17: Curious Kentuckians gather at the site of the soon-to-be Memorial Building. 1909 |

The LFA represented a diverse group of intellectuals, politicians, public servants, artists, and business and religious interests. The LFA's motto, "Organized and incorporated to develop the Lincoln Birthplace Farm into a National Park" possessed great possibility. The Louisville Courier-Journal rejoiced that men of considerable wealth now possessed the property and would be "willing to spend large sums to beautify and ornament it in the proper way." [53] Despite the small, self-imposed subscription limit, the LFA raised the necessary building funds in four years, largely by accepting several generous contributions. The LFA engaged John Russell Pope, a promising architect trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, to design the monument on a grand scale. However, limited subscriptions and an embryonic plan to commemorate Lincoln in Washington, D.C., reduced the grandeur of Pope's original concepts. Running behind schedule, the LFA could not complete the building in time for the Lincoln Centennial. Instead, President Theodore Roosevelt and other dignitaries attended the cornerstone ceremony on the Lincoln Centennial, February 12, 1909. Two years later, President William Taft presided over the dedication ceremonies on November 9, 1911. [54]

After purchasing the Lincoln cabin, the LFA launched its own authenticity investigation. Of the affidavits collected in LaRue County, those of Zerelda Jane Goff, Lafayette Wilson, and Judge John C. Creal were most relevant. Goff stated that the birth cabin logs had been moved to Dr. George Rodman's property but she could not recollect when. Wilson stated that he had moved the birth cabin logs to the farm later owned by John Davenport in March 1860. [55] Judge Creal stated his belief that the Davenport house purchased by Bigham in 1895 was a "comparatively new house." Although the three statements contained obvious contradictions, the LFA remained confident of the cabin's authenticity. [56]

Once completed, the Memorial Building would house the cabin for display and preservation purposes. The LFA erected the cabin for the cornerstone ceremony and then disassembled and stored it until 1911 when it was reerected within the Memorial Building. Unfortunately, the Memorial Building's interior proved too small for both the cabin and visitor circulation. Despite lamenting previous abuses of the cabin, the LFA reduced the sixteen by eighteen foot cabin by sawing off the log ends, reducing it to twelve by seventeen feet. [57]

|

| Figure 18: The Memorial Building and steps as they appeared just prior to dedication, 1911 |

Immediately following the dedication of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial, the LFA pursued its goal of establishing the farm as a national park. Several attempts in 1912, and subsequent years, failed. Finally, a bill introduced in January 1916 passed through committee without amendment, and President Woodrow Wilson signed H. R. 8351 into law July 17, 1916. Wilson, while president of Princeton University, had supported the LFA's goal of creating a national park. The law established Abraham Lincoln National Park by deed of gift from the Lincoln Farm Association accompanied by a $50,000 endowment fund for park maintenance. [58] A complete discussion of the LFA and the design and construction of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial is found in Chapter Three of this study.

NATIONAL PARK DEVELOPMENT, 1916-1935

The bill placed the memorial building, log cabin, and grounds under the authority of the Secretary of War. The secretary determined that a nonresident commissioner and a resident custodian should be appointed to administer the national park. Richard Lloyd Jones volunteered to serve as commissioner, and the government paid him a nominal annual salary of $100. John A. Cissell, a grandson of John Creal, continued his previous service as custodian for the LFA, begun in 1910, under the War Department. Cissell later served as the first park superintendent under the National Park Service. [59]

Cissell and his assistant, W. G. Ragsdale, resided on the farm and cultivated part of the farm acreage, approximately ten acres, in bluegrass and tobacco. Jones, as commissioner, did not visit the site often and made few recommendations for repair and upkeep. By 1926, the park showed signs of neglect, and the Secretary of War determined that the Quartermaster General in Jeffersonville, Indiana, should assume more control over park maintenance. Although Jones kept an advisory position, he no longer acted as commissioner. [60]

As a first course of action, the War Department determined that the annual spring flooding of the plaza and spring needed immediate attention. The flooding deposited a layer of mud and debris on the unpaved plaza that also served as a parking area. Visitors often parked around the flagpole in the court to limit their exposure to the soggy ground. This frequent inundation doubly impacted the visitor because the road connecting the highway and the plaza was not paved. Between 1911 and 1916, the LFA performed few, if any, improvements on the property. Under Richard Lloyd Jones's administration, it also is apparent that no investments in the site were made. After years of neglect, the War Department decided to act in 1928. [61]

The War Department inherited a designed landscape, as well as a memorial building. Pope's plans included the Memorial Building on the knoll and a descending granite stair with pea gravel landings. Pope also included a gravel plaza, approximately seventy feet in diameter, with a central flagpole on axis with the stairs and the Memorial Building [62] At the 1911 dedication, the landscape consisted of stepped grass panels outlined by low hedges with an additional line of hedges that flanked the stairs. A row of Lombardy poplars lay outside each hedged rectangle. At the foot of the stairs lay a grassed plaza that roughly followed the rectangular shape of the basin. A flagpole graced the center of the plaza. [63] The Sinking Spring, located just west of the stairs, remained in its natural state, and the remaining grounds were grassed, wooded, or under cultivation. Visitors entered the court from the south and the east. Four pink granite markers, two incised with "Lincoln Birthplace Memorial," marked the unpaved entrance road. [64]

|

| Figure 19: This photograph shows the Sinking Spring as it appeared prior to War Department modification (circa 1890s). |

In the fiscal year 1928-29, the War Department allocated $5,000 to improve the unpaved approach road, create parking facilities, and provide some measure of flood control. The Engineering Division of the War Department drew plans for widening and paving the existing "old Telford Road." President Herbert Hoover approved on February 14, 1929, more congressional appropriations for repairs and improvement. By June 1929, the War Department had spent approximately $4,000 to replace the deteriorating split-rail fencing and construct the stone steps and retaining walls that form the spring entrance. The War Department erected rail fencing along the west side of U.S. 31E, along the approach road, and around the plaza. [65]

By the close of 1930, the War Department had changed the site through a rigorous construction campaign. It had completed a well system to pump fresh water, including two stone pump houses. To alleviate the flooding problems, the Engineering Division constructed a stone and concrete dam and drain to catch and carry away the excess water that inundated the basin. The War Department also constructed a log comfort station with a terra cotta pipe leaching field, a picnic pavilion, and over 1,000 feet of limestone walkways to improve sanitation problems and visitor circulation. Two sets of granite steps, located on the northeast and southwest facades of the Memorial Building, provided access to the new comfort station, picnic pavilion, and back down to the plaza area. Flagstone paths east and west of the Memorial Building linked the parking area, visitor facilities, the plaza, and the Memorial Building. A stone, three-bay garage, located northeast of the Memorial Building between the pump houses, completed the maintenance facility. Finally, miscellaneous shrubbery was planted along the new paths and around the newly formalized plaza area. [66]

The access road, paved with rock asphalt, consisted of an approximately 1280 foot long drive terminating at an elliptical parking loop approximately 230 feet in diameter. The approach road apparently had little natural vegetation and may have been planted. A stair, consisting of two flights of terraced limestone steps, linked the parking ellipse with the east end of the plaza via a flagstone path. Visitors now approached the Memorial Building from the east via a paved road and flagstone paths.

| ||

|

The basin area incurred the greatest change during the War Department administration. Visitors once entered, generally by car, a grassed basin with a central flagpole that served as both court and parking area. By 1913, gravel covered the court surface and a small circle of grass remained around the flagpole. The War Department formalized the court into a rectangular, flagstone-lined plaza enclosed with waist-high hedges and intended for pedestrians. Cars remained on the parking ellipse. The plaza, completed in 1929, measures approximately two hundred by eighty feet and is oriented on a northeast to southwest axis. Flagstone paths transected the plaza on parallel and perpendicular axes to the Memorial Building. A limestone bench and wall occupied the southeast plaza boundary, and a limestone wall, presumably the dam, formed the southwest plaza boundary in front of the Boundary Oak. The flagpole, surrounded by flagstone paths and a grassed court, occupied the center of the plaza. Limestone benches, formerly located in the open court, were relocated to the landings of the Memorial Building staircase and around the building itself. [67]

The two-story log house, located in a thicket west of U.S. 31E, known as the Old Creal House, remained vacant and in deteriorating condition throughout the War Department tenure. [68]

In 1933, the National Park Service (NPS) assumed responsibility for the Abraham Lincoln National Park from the War Department. Between 1930 and the end of World War II, few improvements or alterations to the Memorial Building and grounds occurred. The NPS inherited a landscape greatly altered from what it perceived as the original design intent of Pope and the LEA. NPS Historian Roy Appleman, upon visiting the site in March 1938, criticized the park's deteriorated condition and overly formal landscaping. The grounds have "too many flagstone and concrete walks, courts, and unnecessary and undesirable buildings." [69]

In 1935, the NPS initiated one of several planting plans. The 1935 landscape work, performed by Public Works Administration laborers between March and June, intended to retain the alterations the War Department had made. The plan called for replacing dying vegetation and elements, such as the poplars, long since removed by the War Department. The NPS also created vegetative screens along the park's southern boundary. [70] Tourist attractions, both on U.S. 3 1E and within sight of the Memorial Building at the Nancy Lincoln Inn, significantly detracted from the site's solemnity. The NPS attempted to visually shield the Memorial Building and plaza from the inn through vegetation, mostly red cedars.

Within the Memorial Building, the reconstructed cabin displayed years of abuse through its unevenly sawn-off log ends, irregular notching, and large gaps in the log walls. A remnant of a flag pole, installed by Dennett and Bigham, remained in the concrete floor of the cabin. The door and window frames were made of sawn lumber and fastened with machine-made nails. Finally, marble plaques addressing the history of the farm and Lincoln's parents contained numerous inaccuracies. [71]

The NPS did not immediately rectify all the problems associated with the Site, particularly those that related to historical accuracy. However, the NPS immediately replaced the concrete cabin floor with a dirt floor and removed the flagpole. The agency also fitted the window and door frames with hand-hewn boards and peg fasteners. The marble plaques were plastered and painted until further study could amend their texts. [72]

The NPS determined that an accurate boundary survey and historic documentation of the Site should be completed first. Historian Benjamin Davis transferred to the park from Mammoth Cave National Park in January 1947 and proceeded to research the origins of the farm, aided by Melvin Weig of Morristown National Historical Park, and to revise the park's interpretive pamphlet. Davis prepared the "Report on the Original Thomas Lincoln Nolin Creek Farm, Based on Court Records" in July 1948. Davis concluded that the park's 110 acres had been part of the original Thomas Lincoln farm. 1 October 1948, Roy Hays, an insurance investigator, published an article entitled "Is the Lincoln Birthplace Cabin Authentic?" Davis submitted documentation that addressed Hays', Louis Warren's, the Lincoln Farm Association's, and his own primary research and concluded that the Rodman tradition was without foundation. [73]

|

| Figure 22: Traditional Birthplace Cabin, 1938 |

Subsequent alterations to park buildings and grounds by the NPS changed some historic fabric associated with the Memorial Building and its grounds, but the feeling and association of the site remained undisturbed. The memorial landscape, consisting of hedges and tall trees flanking the staircase, although replanted, remained intact. In 1941, the NPS razed the log Creal House.

A new sign, reflecting time renamed park, Abraham Lincoln National Historical Park, graced the main entrance some time after 1939. The park also purchased six acres associated with the Boundary Oak, considered a significant Lincoln-era landmark.

|

| Figure 23: The Boundary Oak, 1938 |

In 1959, the park constructed a visitor center on the north side of the parking ellipse, eliminating most of the parking on this portion of the loop. In the same year, the park demolished the picnic pavilion and log comfort station and built two new residences. [74]

The Lincoln Farm Association, the War Department, and the National Park Service accomplished numerous changes at the Sinking Spring Farm from 1909 to 1959. These agencies transformed a few acres of rolling farm country of central Kentucky into a formal secular shrine complete with a classical temple and a carefully manicured landscape.

LINCOLN AND TWENTIETH CENTURY POPULAR CULTURE: AUTOMOBILE

TOURISM

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, visitation to the birthplace and other Lincoln historical sites escalated in direct proportion to improved roads and better automobiles. The War Department sharply felt the effects of increased park visitation. In 1927, over 20,000 visitors annually entered the park. Each year, over 8,000 cars drove onto the property, often bypassing the inadequate park entrance roads and driving over fields. Visitors routinely parked their autos on the court below the flagpole and picnicking visitors left behind their debris. Improvements to accommodate motoring park visitors were expedited, by the late 1920s, before the landscape deteriorated completely. [75]

War Department and NPS administrators also worried about exterior commercial encroachment, generated by auto tourism, and its effect on the park's historic scene. In particular, the Nancy Lincoln Inn, described as a restaurant, souvenir shop, and dance hall, lay just outside the park boundary, south of the Memorial Building, and posed a threat to the historic site's dignity. [76]

Lincoln historic sites dotted the Kentucky countryside and extended beyond the state borders to other Lincoln homesteads in Indiana and Illinois. At least two Kentucky sites, the Nancy Lincoln Inn and the Knob Creek Farm, catered to automobile tourists during the 1920s and the 1930s. [77] Both of these sites and the Lincoln birthplace benefited from federal aid to states for highway construction passed through the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 and the Federal Highway Act of 1921. During the 1920s, the Kentucky Highway Department constructed U. S. 31 E, along older routes, which provided access to all three LaRue County Lincoln historic sites. In addition, the Lincoln Memorial Highway Association began construction of the Lincoln Trail, a memorial highway passing through Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois. The trail follows the route the Lincolns traveled in these states and was originally marked by road signs and historic structures. [78]

|

| Figure 24: Aerial photograph postcard of the Lincoln Memorial (circa 1936) |

The Nancy Lincoln Inn, constructed in 1928, consists of a large, round-log building that houses a souvenir shop, snack bar, and Lincoln memorabilia. The inn operated four, one-room overnight tourist cabins that are currently unoccupied. Jim Howell constructed and operated this concession, located just south of the Memorial Building and plaza, from 1928 to 1946. Family members continue to operate the inn.

The Knob Creek Farm, Lincoln's home from 1811 to 1817, is another roadside tourist attraction along U.S. 31E. In 1931, Hattie and Chester Howard purchased 308 acres along Knob Creek recognized by Lincoln as his childhood home. The Howards erected a large, round-log building and operated a tavern and restaurant there. In addition, the Howards moved a traditional log cabin, built by the Gollaher family circa 1800, closer to U.S. 31E from another location on the farm and opened it to tourists. [79] Both the Nancy Lincoln Inn and the Lincoln Boyhood Home at Knob Creek Farm still operate as tourist attractions.

Two other parks, the Pioneer Memorial State Park and the Lincoln Homestead State Park, commemorate Lincoln's parents and grandparents. Pioneer Memorial State Park, dedicated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934, consisted of an abandoned graveyard and quarry site in 1923. The park is located in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, due east of Bardstown. A Works Projects Administration Federal Writers' Project guidebook to Kentucky describes the Lincoln Marriage Temple, one of many attractions at this historic park. The temple is a red brick building, cruciform in plan, with a central pulpit. The Lincoln Marriage Cabin now stands in place of the pulpit. Reportedly, the cabin was moved from its original site in the Beech Fork Settlement where Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln married. It resembles the Lincoln birthplace cabin. [80]

Lincoln Homestead State Park, located in Springfield, Kentucky, southeast of Bardstown, contains the purported childhood home of Nancy Hanks Lincoln, a two-story, hewn-log house. In the same park, the Bathsheba (Bersheba) Lincoln Cabin, a reproduction of Lincoln's grandmother's home, is exhibited. The WPA guide recommended the historical reenactments of the Lincoln marriage ceremony held yearly on June 12. [81]

All of the Lincoln sites in Kentucky clearly profited from the expansion of highways in the state and their often tentative historic connections to Lincoln. Other sites and institutions in the state have liberally adopted the name Lincoln, regardless of any historic link to the Lincoln family, because the name carries specific connotations for Americans. Whether the intent is commemorative or economic, the name and memory of Lincoln is evocative.

|

| Figure 25: The Mission 66 Visitor Center, 1959 |

INTEGRITY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES

For this context, historic resources need to retain integrity of design, location, feeling, setting, and association. Some alteration of historic materials is considered acceptable as long as the original design intent remains intact. For example, the plaza walkways retain integrity of location, design, feeling, and association although the historic fabric has been removed. The workmanship of the limestone structures is evident although some deteriorated materials may have been replaced with nonhistoric fabric. The setting is largely undisturbed, although numerous changes within the historic period occurred. The historic resources classified as noncontributing lack integrity of setting, design intent, or feeling. For example, the entrance drive and parking area, because of nonhistoric intrusions, have lost some of the original pastoral feeling associated with the long winding road and graceful ellipse. Because feeling and association are largely subjective, the LCS team relied heavily on photographic evidence and several key site plans and planting plans to determine the level of integrity based on these aspects.

|

| Figure 26: Aerial photo of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial complex, 1959. Note the buildings of the Nancy Lincoln Inn in the foreground. |

CONTRIBUTING RESOURCES

Memorial Building and Steps: A complete description of the building and staircase can be found in Chapter Three.

Memorial Landscape: This includes the landscape elements represented in Pope's design plans; the landscape that accompanied the building's dedication in 1911; the changes effected by the War Department between 1929 and 1930; and the additional landscaping initiated by the NPS in 1935, which restored some of the original landscape configurations altered over time.

The landscape that accompanied the Memorial Building and steps at the 1911 dedication consisted of three elements: two sets of hedges and a row of Lombardy poplars located behind the hedges. The stairs are flanked by one rectangular hedge and a taller hedge row on the outer edge of the rectangle. Grass covered the exposed ground among the hedges and within the mown basin area at the foot of the stairs. Within two years, gravel replaced the grass in the court and a circle of grass surrounded the centrally located flagpole.

In 1929-1930, the War Department reconfigured the landscape by reconstructing the court and adding numerous stone structures. The War Department enlarged the court to a rectangular plaza, approximately two hundred by eighty feet, oriented on a northeast by southwest axis. Flagstone paths transected the plaza with the longest axis parallel to the Memorial Building. These paths are now laid with a pea gravel aggregate, but preserve their original orientation. A coursed limestone bench, approximately eight feet long and four feet tall, is set in a forty-four foot wall and serves as the southwest plaza boundary. The Sinking Spring lies directly south of the Memorial Building stairway and has coursed limestone walls, progressively taller from the top of the stair to the spring, that create a stair wall and also serve as a retaining wall behind the spring. Three runs of eight flagstone steps descend to a flagstone platform, which encircles the spring pool, approximately six to eight feet below. Two drain pipes are located in this sinkhole and are connected to storm drain pipes under the plaza. Two stone benches are affixed to the south wall at the platform level. The final plaza structure is a limestone and concrete stair that descends from the parking ellipse to the northeast plaza entrance. This thirteen foot wide stair consists of two runs of twelve and thirteen steps and two coursed limestone walls with stone pedestals. The steps, likely originally flagstone, are now concrete and the landings are paved with pea gravel aggregate.

Boundary Oak Site: The Boundary Oak was one of the most significant features at both the historic Sinking Spring Farm and the park. Until its death, the great white oak remained the "last living link" to Abraham Lincoln and was of considerable historic interest and value. The tree served as a boundary marker and survey point for determining property lines. The Boundary Oak was first identified as a specific boundary marker in the original 1805 survey of the farm. The tree was located less than 150 yards from the cabin where Abraham Lincoln was born in 1809. Be fore its death in 1976 and its removal in 1986, the Boundary Oak reached 6 feet in diameter, 90 feet in height, and had a crown spread of 115 feet.

Three separate analyses of a cross section of the tree concluded that the large oak sprouted sometime in 1781. The cross section is now located in the Visitor Center and serves as a template for a chronology of Abraham Lincoln's life and related events. Although the tree is gone, its stump remains as the primary identifying feature of the original farm boundary.

Sinking Spring: The Sinking Spring is a natural landscape feature related to Abraham Lincoln's formative years. Early NPS interpretation of the spring noted how "the infant child, Abraham, had his earliest drinks from these waters." [82] This simple but evocative statement is no doubt true; such springs usually dictated the site for a farm residence on the Pennyroyal. In addition, the Lincoln birthplace farm had always taken its name from the spring instead of the property's owner, being variously known as "The Sinking Spring," "Rock Spring," and "Cave Spring" farm. [83] The hydrology of the spring is typical of that in the Pennyroyal, and the many small ponds that dot the landscape surrounding the park are likely similar sinking springs that have collapsed. [84] Drainage in the Pennyroyal is achieved less by surface rivers and streams than it is by subterranean ones, and the Sinking Spring is a singular example of this larger drainage patter.

NONCONTRIBUTING RESOURCES

Boundary Oak Storm Drain and Dam: Although two boxlike structures appear on War Department site plans in 1931 and 1932 and on NPS planting plans for 1935, it is unclear if the existing limestone wall and drain represents either of these structures. No photographic evidence is avail able that would verify this hypothesis. Thus, these structures are considered noncontributing until further documentation is available.

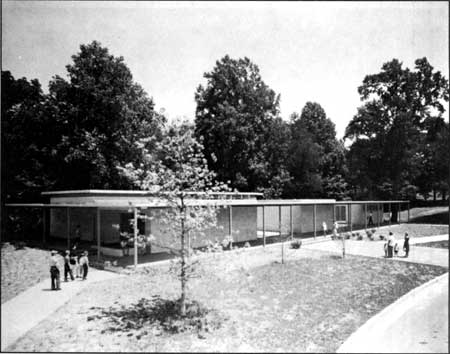

Employee Residences: Two, single-story ranch-style houses for park employees were constructed in 1959 as part of the Mission 66 program. The houses do not contribute to the memorial landscape. Please note the discussion below on these properties' potential eligibility to the National Register.

Visitor Center: The Visitor Center was constructed in 1958 and 1959 as part of the Mission 66 program. The building was designed by the NPS's Easter Office of Design and Construction (EODC) and built by a Lexington, Kentucky, construction firm. The single-story, flat-roof building has been altered over the years; the most observable change was the installation of a glass atrium over the building's originally open entryway.

A recently published study on NPS visitor centers has provided a context that will help in evaluating their significance. [85] Of the Park Service's estimated 114 Mission 66 visitor centers, only five to date have been recognized for their architectural significance. Three of these five properties were declared National Historic Landmarks early in 2001. The remaining visitor centers, however, including the one under discussion here, were based on generic plans and what the author of the aforementioned visitor center study noted as an "assembly-line" mentality. Although the same author also notes the "potential historic value" of all Mission 66 visitor centers, because the Lincoln Birthplace visitor center was based on the standardized designs of the EODC and because alterations to the building have compromised its original design, it is considered noncon- tributing at this time. At the time of this writing, the entire Mission 66 program and its architecture is being reexamined, and a theme study is being written to guide the determination of the National Register eligibility of individual properties. The Mission 66 structures at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site should be reevaluated when the theme study is completed.

Maintenance Garage

A single-story, four-bay maintenance garage is located northeast of the Memorial Building.

Storage Building and Pumphouse

Two War Department-era structures, a storage building (previously used as the Superintendent's office) and a pumphouse, are on either side of the park's maintenance garage. These small stone structures, although well over 50 years old, were not part of the program of commemoration at the Site.

NOTES

1. Among the major centennials were the battles of Lexington and Concord (1875), the Declaration of Independence (1876), the British surrender at Yorktown (1881), and the Constitution (1888).

2. The apotheosis of Lincoln was initially a northern phenomenon. Some southerners lamented the likely effects on the South of Lincoln's death, but few expressed regret at their adversary's passing. Later in the century, a general spirit of reconciliation enhanced Lincoln's reputation in the South but resulted in few memorials. A 1952 compilation of eighty-seven major Lincoln statues did not include a single work in a former Confederate state (Oates, Abraham Lincoln: The Man Behind the Myths, 21-23; F. Lauriston Bullard, Lincoln in Marble and Bronze [New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1952], 8-9).

3. David Donald, Lincoln's Herndon (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948), 167.

4. Roy Basler, The Lincoln Legend: A Study in Changing Conceptions (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1935), 3-5; Donald, 164-68; Oates, Abraham Lincoln. The Man Behind the Myths, 4-5

5. Oates, Abraham Lincoln: The Man Behind the Myths, 9; Victor Searcher, The Farewell to Lincoln (New York: Abingdon Press, 1965), 51-93; Neely, 121-22.

6. Walt Whitman, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd," Leaves of Grass (based on the text of the 9th ed., 1892) (New York: Signet, 1955), 265-71.

7. Donald, 168; Basler, 35-37.

10. The book's poor sales resulted as much from an inept, nearly bankrupt publisher as from Herndon's refusal to exclude information that didn't conform with Lincoln's saintly image (Donald, 334-42).

11. Neely, 145-48, 177-78; Donald, 170-83,212-17, 322-34,370-73; Oates, Abraham Lincoln: The Man Behind the Myths, 6-7.

12. John D. Hicks, The American Nation: A History of the United States from 1865 to the Present 3d ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1955), Appendix, xviii; John A. Garraty, The New Commonwealth, 1877-1890 (New York: Harper & Row, 1968), 1-4, 15.

13. Garraty, 78-83; Louis M. Hacker and Benjamin B. Kendrick, The United States Since 1865 4th ed. (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1949), 157.

14. Garraty, 139; Hacker and Kendrick, 162-64.

15. Sean Dennis Cashman, America in the Gilded Age 2d Ed. (New York: New York University Press, 1988), 15-16; Hicks, 197-99; Garraty, 179,201-3.

16. Quoted in Hacker and Kendrick, 61.

17. Donald, 168; Hacker and Kendrick, 61-64.

18. Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877-1920 (New York: Hill & Wang, 1967), 39.

19. James D. Hart, The Popular Book:A History of America's Literary Taste (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1950), 161,201-23.

21. C. A. Weslager, The Log Cabin in America: From Pioneer Days to the Present (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1969), 261-70.

22. Weslager, 288; Oates, With Malice Toward None, 180-85; Thomas, 216.

23. Robert G. Ferris, ed., The Presidents: Historic Places Commemorating the Chief Executives of the United States (Washington, D.C.: 1976), 577; Charles B: Hosmer, Jr., Presence of the Past: A History of the Historic Preservation Movement in the United States Before Williamsburg (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1965), 47-51.

25. Neely, 309-10; F. Lauriston Bullard, Lincoln In Marble and Bronze (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1952), 58-59.

26. Neely, 114; The National Parks: Index 1991, 31.

27. Bullard, 28-29,40,46,67,79, 144-50.

28. Hosmer, 72-74; The National Parks: Index 1991, 31, 39.

29. Merrill D. Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 55-60.

30. The three Lincoln statues in Washington were standing figures mounted on low pedestals.

30. Bullard, 333-35; Bates Lowry, Building a National Image: Architectural Drawings for the American Democracy, 1 789-1912 (Washington, D.C.: National Building Museum, 1985) 83-85; Norman T. Newton, Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971), 403-7.

32. Neely, 173-74; McPherson, 295-96.

34. Hays, 128-29. Lincoln himself was vague concerning the location of his birthplace, remembering it was located on Nolin Creek, but not much else.

35. Gross wanted to purchase 110 acres that represented a portion of the original 348.5 acre farm owned by Thomas Lincoln. In 1894, Richard Creal resided on the farm in a two-story log house, erected circa 1860.

36. Both of these efforts, one for George Washington and the other for Andrew Jackson, preserved the residences of these national leaders. Ultimately, the two ladies societies responsible for preserving the properties raised funds to restore the homes by charging admission fees. Because no cabin existed on the Sinking Spring property, it is unclear how Gross intended to follow the example of Mount Vernon or the Hermitage as Pitcaithley suggests. See Dwight T. Pitcaithley, "A Splendid Hoax: The Strange Case of Abraham Lincoln's Birthplace Cabin," paper presented at the 1991 Annual Meeting of the Organization of American Historians, 3; Hosmer, 51-61,69-72; Hays, 129.

38. Roy Hays's 1948 article "Is the Lincoln Birthplace Cabin Authentic?" thoroughly examined the traditional birth cabin's origins. NPS historian Benjamin H. Davis also examined the cabin's authenticity in three reports: "A Report on the Abraham Lincoln Traditional Birthplace Cabin," May 16, 1948; "Report of Research on the Traditional Abraham Lincoln Birthplace Cabin" February 15, 1949; "Comments on Statements Made by Dr. L. A. Warren Concerning the Traditional Lincoln Birthplace Cabin," October 7, 1950.

39. Davis, "Report of Research on the Traditional Abraham Lincoln Birthplace Cabin," 32-33; at the Nashville and Buffalo expositions, the cabin measured sixteen by eighteen feet (Weslager, 290).

40. In September 1895, Russell Evans, a local Elizabethtown photographer, took pictures of the Lincoln farm and cabin that revealed the improvements Bigham had made upon the property and the cabin itself. Hays, 132; also, Gloria Peterson, Plates I and II. Various affidavits collected by the LFA also dispute the original location of the cabin upon the knoll or closer to the spring. See Davis, "Report of Research on the Traditional Abraham Lincoln Birthplace Cabin," 7-8,13,24,28,30-31.

41. Davis, "Report of Research on the Traditional Abraham Lincoln Birthplace Cabin," 2-3.

42. Davis, "Report of Research on the Traditional Abraham Lincoln Birthplace Cabin," 34-5; Hays, 36-7; Weslager, 290.

48. Thomason, E19-E22, E24-E25.

49. Bullard, 123-24, 126; Thomason, E24-E25.

51. Hays, 155-56; Richard Lloyd Jones, "The Lincoln Birthplace Farm," Collier's Weekly (February 10, 1906): 12-20.

52. Hays, 157-58; Photographs founding. Peterson, Plate VI.

53. Louisville Courier-Journal, August 29, 1905, as quoted in Peterson, 21. Several notable members and committee chairs included: Samuel Clemens, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, William Taft, Henry Watterson, August Belmont, Cardinal Gibbons, Robert J. Collier, Clarence Mackay, and Ida Tarbell.

55. Because the Republican Party did not nominate Lincoln for the presidency until May 1860, the supposed moving of his birth cabin in March 1860 was probably not motivated by veneration for Lincoln.

56. G. Peterson, 14-15,31-33; Hays, 159-61; the affidavits are reproduced in Davis, "A Report on the Abraham Lincoln Traditional Birthplace Cabin," 9-13.

57. Davis, "A Report on the Abraham Lincoln Traditional Birthplace Cabin," 30; G. Peterson, 26-28; Weslager, 291.

58. All information pertaining to the War Department administration of the site is documented in G. Peterson, who conducted primary research with War Department records at the National Archives. The actual deed of gift was conveyed to the War Department on June 19, 1916; Peterson, 15-37, 99. The LFA referred to the farm as the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial, and two pink granite markers incised with this title at one time marked the farm entrance. Under the direction of the War Department, the site was called the Abraham Lincoln National Park; the name was changed in 1939 to the Abraham Lincoln National Historical Park by the National Park Service to distinguish this historic park from natural parks; in 1959, the park nomenclature again was changed to the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site; G. Peterson, 65, 78.

62. John Russell Pope, "Terrace Stairs" and "Block Plan" 1908. Drawings on microfilm, National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office, Atlanta.

63. Two photographs dated July 27, 1913 illustrate the existing conditions prior to the War Department administration. Photographs courtesy of the Filson Chub, Louisville, Kentucky.

64. Ida M. Tarbell describes in In the Footsteps of the Lincolns (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1924) that "You approach the monument by a winding driveway, on each side of which the natural growth of the land has been left.... The landscape gardening," she continues, "simply protects the drive, the staircase, the temple itself from the encroachment of the woods, leaving the natural setting undisturbed" (Tarbell, 95-96). Also, photographs in Warren, facing page 97. There is some question regarding the natural state of the Sinking Spring. In 1926, Warren in Lincoln's Parentage and Childhood illustrates a coursed wall and stone stair leading down to an overgrown spring, with a natural rock ledge. Early documentation related to the spring has not been uncovered. The four granite markers also have not been accurately documented. Warren illustrates two of the short square blocks in a pre-1926 photograph. However, the function or location of the incised tablets has not been determined (Warren, illustrations opposite pages 97 and 144); Undated photographs, c. 1911 Dedication Ceremony, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site, Kentucky.

66. G. Peterson, 44, 52-54. See also Plates XI, XIII, XV, and XVII. For comparison, 1913 photographs in possession of The Filson Club, Louisville, Kentucky, illustrate the site prior to any plaza construction; also, Warren, photographs facing page 97 depict the informal plaza and the declining health of the Lombardy poplars. "Contour Map of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial" by the Office of Constructing Quartermaster, Hodgenville, Kentucky, June 30, 1931, is a good site plan illustrating the relationship of all the structures to one another.

67. Two War Department site plans illustrate topography, landscaped and natural vegetation, and built structures. "Contour Map," 1931 and "Reservation Map," Lincoln Farm National Monument, compiled by the Construction Division, Office of the Quartermaster General, March 1932. In addition, photographs illustrate the plaza and parking area as they appeared in 1929 and 1934 (Peterson, Plates XI and XV).

69. G. Peterson, 63; Photographs from 1932 indicate that none of the poplars remained and one row of hedge had been removed, presumably by the War Department (The Filson Club, Louisville, Kentucky).

70. "Planting Plan, Approach Area, Abraham Lincoln National Park," compiled by Eastern Division, Branch of Plans and Design, National Park Service, January 25, 1935; Peterson, 57-58.

73. G. Peterson, 58, 64,93-94; Davis, "Comments on Statements by Dr. L.A. Warren Concerning the Traditional Lincoln Birthplace Cabin," 1-3.

78. Thomason, E26-E27. Many of these Lincoln historic sites and structures associated with the Lincoln Highway are based on conjectural evidence. For example, the Lincoln family resided at the Knob Creek farm, but both the authentic mid-nineteenth century cabin and rusticated tavern/lodge are not originally associated with Lincoln. In addition, much of the original signage is no longer in place due to theft and lack of maintenance.

80. Federal Writers' Project, 171-72; Weslager, 294.

81. Weslager, 293; Federal Writers' Project, 379.

82. Taken from interpretive text related in a 1947 letter from Regional Director Elbert Cox to the superintendent of Mamouth Cave.

84. Nevin M. Fenneman, Physiography of the Eastern United States (New York: McGraw Hill, 1938), 419-421.

85. See Sarah Allaback, Mission 66 Visitor Centers: The History of a Building Type (Washington DC: GPO, 2000).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

abli/hrs/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2003