|

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace

Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter One:

THE IMPORTANCE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND HIS BIRTHPLACE

|

| Figure 3: President Lincoln as photographed by Mathew Brady, 1861 |

Abraham Lincoln occupies a towering position in American history and folklore. As president during the Civil War from March 1861 to April 1865, Lincoln guided the nation through its severest test Vilified by opponents during his presidency, Lincoln quickly became one of the most venerated American leaders following his assassination on April 14, 1865. [1] Real as Lincoln's achievements were winning the war, preserving the Union, and emancipating a race he occupies an even more exalted position in American mythology. As historian and Lincoln biographer Stephen B. Oates observed, the Lincoln of myth perfectly embodies quintessential American virtues: "honesty, unpretentiousness, tolerance, hard work, a capacity to forgive, a compassion for the underdog, a clear-sighted vision of right and wrong, a dedication to God and country, and an abiding concern for all." [2] For over a century, the desire to understand the origin of these virtues has inevitably led Lincoln biographers, as well as the general public, to Kentucky's Sinking Spring Farm; thus the place of Lincoln's birth and first two years of life remains historically significant, both as a site of pilgrimage and as an important and enduring place in the American imagination.

LINCOLN'S FRONTIER BACKGROUND

Lincoln's obscure birth in a frontier log cabin and his backwoods upbringing became central elements in the Lincoln story. Lincoln cultivated an image of himself as a self-made man, because it had strong voter appeal in mid-nineteenth-century Illinois. After 1865, the story of Lincoln's journey from a log cabin to the White House was told and retold until it came to exemplify the best possibilities in American life. Biographers and others often exaggerated the poverty and obscurity of Lincoln's birth to highlight the magnitude of his later accomplishments. In fact, Lincoln's father Thomas was a respected and relatively affluent citizen of the Kentucky backcountry. Although he moved frequently, Thomas Lincoln had good credit, maintained from one to four horses throughout his adult life, served on juries, and was chosen to supervise the maintenance of a road near one of his farms. [3]

|

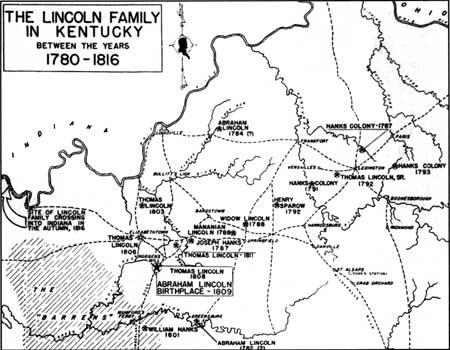

| Figure 4: Map showing the Lincoln family's Kentucky homesteads from 1780-1816 (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The son of a Virginia farmer, Thomas Lincoln moved to Jefferson County, Kentucky (then part of Virginia), with his parents about 1782. The Lincolns were among thousands of Virginia and North Carolina residents attracted to the virgin land lying beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Inspired by the exploits of Daniel Boone, and encouraged by organizations like Richard Henderson's Transylvania Company, the settlers of "Kaintuckee" expected a better life at the end of the Wilderness Road. Between 1782 and 1792, the state of Virginia issued 10,000 land grants in its Kentucky counties to Revolutionary War veterans. Virginia relinquished its claims to Kentucky in 1789, and Congress admitted it as the fifteenth state in 1792. [4]

From the age of sixteen, Thomas Lincoln lived in a number of Kentucky and Tennessee communities; eventually he settled in Hardin County, Kentucky. In 1803, he paid £118 in cash for a 238-acre farm on Mill Creek, eight miles north of Elizabethtown, the county seat. [5] There is no evidence that he ever worked this farm. Thomas Lincoln married Nancy Hanks in 1806, and built a log house on one of two lots that he owned in Elizabethtown. He worked briefly as a carpenter in Elizabethtown before purchasing the Sinking Spring Farm in December 1808 for $200 cash and the assumption of a small debt due a previous owner. [6] The property was two to three miles south of Hodgen's Mill, established in the 1790s, which became the nucleus of the town of Hodgenville. Thomas Lincoln's farm had generally poor soil and only a few scattered trees, but its freshwater spring and upland location were good inducements for settlement. Lincoln farmed a small portion of his acreage and continued to do carpentry jobs, likely for the many farmers nearby that Tom and Nancy knew before they moved from Elizabethtown. [7] Thomas Lincoln's ownership of this land became more of a legal struggle than an agricultural one, and a prior claim asserted in a lawsuit filed by a Richard Mather deprived the Lincolns of their Sinking Spring Farm after they had lived there only two years.

In 1811, the Lincolns moved to a 230-acre farm on Knob Creek owned by a George Lindsey. Having spent money for legal counsel in the ongoing Mather lawsuit, Thomas could only afford to lease 30 acres of the Lindsey tract; he selected the bottomland portion of it on which to establish yet another farm. Knob Creek is a tributary of the Rolling Fork River, and the creek valley on this new farm contained some of the best farmland in Hardin County. A well-traveled road from Bardstown, Kentucky, to Nashville, Tennessee, ran through the property. Abraham Lincoln's earliest recollections were of the Knob Creek place. [8]

Far from being an impoverished vagabond, Thomas Lincoln during these Kentucky years was a respected community member and a successful farmer and carpenter. Had they been able to secure clear title, the Lincolns might well have stayed at the Sinking Spring Farm. [9] After being forced off that farm, Lincoln continued legal action until the case was settled against him in 1815. His only recourse in 1811 was to find a place nearby where he could raise his family and continue to argue his case in the Hardin Circuit Court. Thomas Lincoln had title problems with all three of his Kentucky farms. When he sold the Mill Creek farm in 1814, he lost money because it turned out to be smaller than he had believed. Thomas abandoned the Sinking Spring Farm against his wishes, and in 1815, an out-of-state claimant sought to eject him from the Knob Creek farm. Ironically, Thomas Lincoln became a competent land surveyor during this time; unfortunately he never was able to survey Kentucky land that he owned. Frustrated over the tangled status of Kentucky land titles, Thomas moved his family to Indiana in 1817, when Abraham was seven. [10] The federal government under the provisions of the Ordinance of 1785 had surveyed Indiana, making Indiana titles more secure. It is just possible that his father's problems with land titles had some influence on Abraham Lincoln's later decisions to learn surveying and become an attorney.

LINCOLN'S EARLY LIFE

|

| Figure 5: The lawyer Abraham Lincoln, 1858 |

One element of the Lincoln legend is accurate: Lincoln received limited formal schooling—amounting to perhaps one year in total in the remote rural communities of Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois where he was reared. Lincoln grew to manhood in Indiana, working on his father's farm and doing odd jobs for neighbors. He early showed a preference for intellectual over manual labor and a driving ambition to better himself. Making his home in New Salem, Illinois, from 1831 to 1837, Lincoln read the law while keeping a store and in 1834 was elected to the state legislature at the age of twenty-five. Lincoln rapidly rose to a leadership position within the Whig Party in Illinois, becoming minority leader in the legislature and directing the successful effort to move the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield, which was Lincoln's home from 1837 to 1861. [11]

Lincoln was admitted to the bar in 1836 and began a legal career that, along with politics, became the main professional interest of his life. As a lawyer, Lincoln had his share of divorce cases, property disputes, and criminal trials. By the 1850s, however, Lincoln was widely recognized as one of the ablest appellate court advocates in Illinois. He argued 243 cases before the Illinois Supreme Court, including important suits on behalf of the Illinois Central Railroad for which he received large fees. Lincoln served a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives, in 1847-1849, under an informal arrangement with other prominent Sangamon County Whigs, who agreed to rotate the seat among them. [12]

In the early 1850s, Lincoln devoted himself to his lucrative law practice and was relatively inactive politically. The 1854 repeal of the Missouri Compromise reopened the volatile debate over slavery in the territories. Lincoln, in common with hundreds of thousands of "free-soil" advocates across the Midwest, plunged himself into political action. A new party committed to preventing slavery's extension and calling itself the Republican Party, arose in the Midwest in the summer of 1854 and rapidly gained adherents. The Whig Party, always a minority party in Illinois, began to split over the slavery issue, and Lincoln distanced himself from it. In 1856, he became an energetic member of the Republican Party. The first Republican presidential convention in 1856 nominated John C. Fremont, the Western explorer. Lincoln attracted national attention by garnering 110 votes for the vice-presidential nomination, which ultimately went to William Dayton of Ohio. [13]

Receiving the Republican nomination for U.S. Senator in 1858, Lincoln engaged in a series of debates with Stephen A. Douglas, the Democrat candidate, in seven Illinois cities. The debates centered on the issue of slavery extension and were closely followed across the nation. Throughout the debates, Lincoln branded slavery an injustice and opposed its spread, while distancing himself from abolitionist doctrines. Douglas, who had presidential ambitions, attempted to mollify free-soil Illinois voters without antagonizing the South, and Lincoln exploited the contradictions in Douglas's position. Douglas supported the right of slaveholders to take slaves to the territories, yet contended that territorial governments could effectively bar slavery through hostile legislation. Douglas won the Senate seat [14] by emphasizing the latter point, but his stance angered Democrats in the slave states. [15]

By the late 1850s, the Whig Party had virtually disappeared, and the Democrat Party was fracturing over the slavery question. In 1860, Douglas was the presidential candidate of the northern Democrats, while John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky was the choice of the southern branch of the party. A group of former Know-Nothings and diehard Whigs formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell of Tennessee. The Republicans convened their nominating convention in Chicago, with the Illinois delegation promoting favorite son Lincoln. Better-known Republicans William Seward of New York, Salmon Chase of Ohio, Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania, and Edward Bates of Missouri—contested the nomination with Lincoln. The convention nominated Lincoln on the third ballot, largely because he had fewer liabilities than the other candidates. [16]

LINCOLN AS PRESIDENT

The presidential election of 1860 was actually two separate regional contests. Lincoln vied with Douglas for northern votes, while Breckinridge and Bell contested for the South. The electoral arithmetic and strong free-soil sentiment in the North favored the Republicans; Lincoln won with a clear majority in electoral votes, but only forty percent of the popular vote. Believing that the Republican victory augured the end of slavery, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas seceded from the Union before Lincoln's inauguration and established the Confederate States of America. Upon assuming office on March 4, 1861, Lincoln decided to assert the Federal government's sovereignty by resupplying the besieged U.S. Army garrison at Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The Confederate government ordered an attack on the fort, signaling its intention to fight for its independence and igniting the Civil War. Following the Union surrender of Fort Sumter on April 14, 1861, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas joined the Confederacy. [17]

As a minority president of a war-torn republic, Lincoln faced enormous difficulties: raising and equipping armies, finding competent generals, and maintaining civilian morale. The U.S. Constitution made no provision for dealing with rebellious states, and Lincoln frequently improvised, relying on a broad interpretation of his war powers. Particularly controversial was his jailing of suspected southern sympathizers without charges, in defiance of Federal court decisions. Lincoln demonstrated considerable political skill by maintaining popular support for the war despite disastrous defeats for Federal armies and mounting casualties. [18]

Union war strategy focused on blockading southern ports, controlling the Mississippi River, and invading the southern states. Through the first three years of the war, Union armies advanced steadily in the West, but failed to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. Lincoln aimed to preserve the Union and was willing at first to protect slavery if it furthered that goal. As the war dragged on and the importance of slave labor to the southern war effort increased, Lincoln and the Republican Party moved to adopt emancipation as a war policy. Lincoln decided in July 1862 to free slaves in the rebellious states but awaited favorable military news to act. At the Battle of Antietam in western Maryland (September 17, 1862), the Army of the Potomac under General George McClellan turned back General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Within days, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in the states still engaged in rebellion as of January 1, 1863. De facto freedom for blacks already prevailed in areas liberated by Union troops; the proclamation was designed to undermine Southern resistance, encourage blacks to rally to the Federal effort, and keep England from recognizing the Confederacy. [19]

|

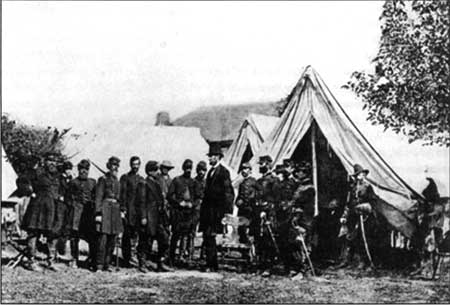

| Figure 6: President Lincoln meets with General McClellan at Antietam, 1862 |

Two Federal victories in early July 1863 marked a turning point in the war. Union General Ulysses S. Grant occupied Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 4, 1863, giving the Federals complete control of the Mississippi River and depriving the Confederacy of reinforcements and supplies from Texas, Arkansas, and most of Louisiana. In the east, General George Meade repulsed Lee's second invasion of the North at the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (July 1-3, 1863). Although the North would continue to suffer setbacks and terrible casualties, the tide was running in its favor. [20]

The 1864 presidential election year tested both Lincoln's leadership and northern commitment to the war. Federal control of the Mississippi and an increasingly effective naval blockade put severe strains on the Confederacy. In March 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to the rank of lieutenant general and made him general in chief of all Federal armies. Grant moved east to personally supervise the operations of the Army of the Potomac and put General William T. Sherman in charge of all western armies. Grant ordered simultaneous advances by the Army of the Potomac on Richmond and by three combined western armies under Sherman's personal command into Georgia. The Confederacy aimed to hold off the northern armies until after the November election, hoping that a Democrat willing to negotiate southern independence would defeat Lincoln. [21]

Northern civilian morale was strained during the spring and summer of 1864. Grant pushed Lee back in Virginia while Sherman repeatedly outmaneuvered his Confederate foe in north Georgia, but at the cost of 90,000 overall Union casualties in four months. In August 1864, trench warfare outside Petersburg held Grant in check, while Sherman besieged Atlanta. Four years of war seemed to have brought a stalemate, and northern antiwar sentiment mounted. Lincoln's July 1864 draft call for 500,000 more troops added to northern gloom. In this climate, Lincoln anticipated losing the election to Democrat George McClellan. Then Atlanta fell on September 1, 1864, providing a huge boost to northern morale and a corresponding southern letdown. Believing that a final military victory was at hand, northern voters gave the Republicans an overwhelming victory in November. [22]

Vindicated at the polls, Lincoln and the Republican Party pursued the war to a successful conclusion. Sherman's army marched through Georgia and South Carolina, confiscating or destroying anything of value to the Confederacy. Richmond fell in early April 1865; Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9. Lincoln was giver little time to formulate his plans for reconstructing the South. On April 14, 1865, Good Friday, Lincoln attended a performance at Ford's Theatre. John Wilkes Booth, an actor and fanatical southern sympathizer, burst into the president's box and shot him. Carried to the Petersen house across Tenth Street from the theater, Lincoln died shortly after seven a.m. the next day. [23]

The news of Lincoln's assassination instantly tempered northern euphoria at the war's end with grief and anger. The conversion of Lincoln from an outstanding, if embattled, wartime leader to a sainted martyr to the Union cause began almost immediately. As described below in Chapter Two, Lincoln's reputation steadily grew following his death; his rise from humble beginnings to momentous presidential achievements commanded the respect of millions. The site of Lincoln's birth in Kentucky was meaningful, not only as the birthplace of a famous American, but as a symbol of the unlimited possibilities of American life. The memorial at the Lincoln farm commemorates Lincoln the man and much of what he came to symbolize for Americans.

|

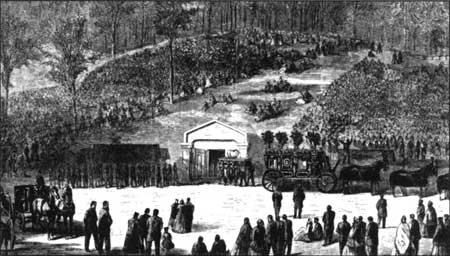

| Figure 7: This 1865 woodcut from Harper's Weekly depicts the scene at Lincoln's interment at Oak Ridge Cemetery near Springfield, Illinois. |

NOTES

1. Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Toward None: The Life of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 431-32.

2. Stephen B. Oates, Abraham Lincoln: The Man Behind the Myths (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 16.

3. Thomas, 7; Oates, With Malice Toward None, 5-6; Thomas L. Purvis, "The Making of a Myth: Abraham Lincoln's Family Background in the Perspective of Jacksonian Politics," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 75 (Summer 1982): 149-50.

4. Thomas, 4-5; Thomason, E2-E3.

5. The money for this purchase came from the sale of land inherited by Thomas and Mordecai Lincoln from their father (Beveridge, vol. I, 12).

6. Property records indicate that Thomas Lincoln believed he had purchased a 300-acre farm; a survey of the property in 1837 revealed that the tract actually contained 348.5 acres (Warren, 83-87).

7. Kent Masterson Brown, "Report on The Title of Thomas Lincoln to, And The History of, The Lincoln Boyhood Home Along Knob Creek in LaRue County, Kentucky" (Atlanta: National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office, 1998), 31.

9. Kent Brown convincingly argues that Thomas Lincoln was a "victim" of David Vance, one of four people involved in the 1808 Sinking Spring Farm transaction. Vance, who never appeared at the Hardin Circuit Court to testify in his defense, already had four pending lawsuits against him relating to land deals (Brown, 21).

10. In notes supplied to a journalist in 1860 for a campaign biography, Abraham Lincoln wrote that the family's removal to Indiana "was partly on account of slavery, but chiefly on account of the difficulty in land titles in Ky." "Autobiography Written for John L. Scripps," The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Roy P. Basler, ed. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), IV: 61-62.

11. James O. Randall, "Abraham Lincoln," in Dictionary of American Biography, ed. Dumas Malone (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1946), 243-44.

13. Randall, 246-47; Oates, With Malice Toward None, 127-28.

14. State legislatures chose U.S. senators in this period; Douglas prevailed because the Democrats maintained control of the Illinois legislature.

17. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 223,234-35,271-74,278-83; Randall, 249-51.

19. McPherson, 333-34, 557-58; Oates, With Malice Toward None, 317-33. Abolitionist sentiment was strong in Britain, which had outlawed slavery in its empire in 1833 (John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans [New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1967], 347).

20. Oates, With Malice Toward None, 352-53.

21. McPherson, 718-22; Oates, With Malice Toward None, 383-85.

22. McPherson, 773-75, 788-91, 805-6; Oates, With Malice Toward None, 387-97,400-1.

23. McPherson, 846-50; Oates, With Malice Toward None, 420-33.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

abli/hrs/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2003